Panel discusses intersectional feminism, justice

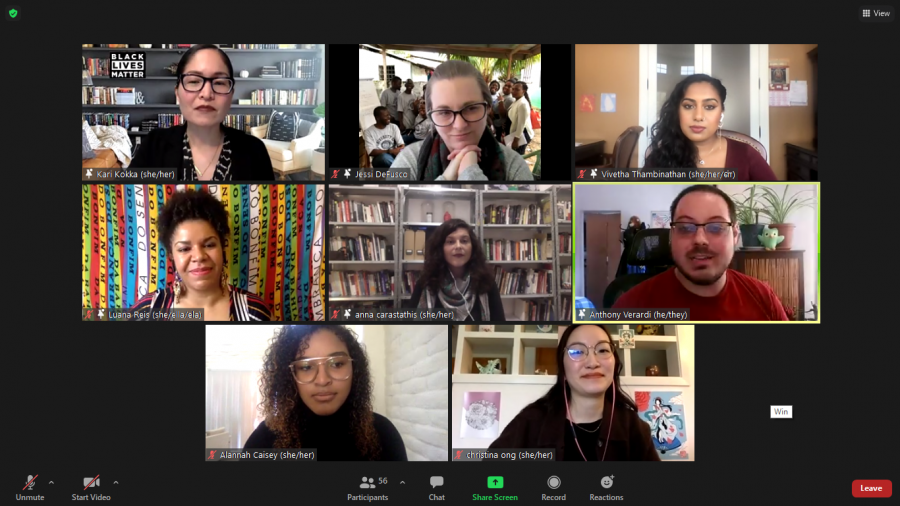

Pitt’s Global Hub a panel Wednesday afternoon called “What is Justice?: Contemporary Perspectives on Global Feminisms” that focused on the current socio-political climate, transnational feminism, anti-Blackness and global social justice issues.

March 12, 2021

As a Black Brazilian woman, Luana Reis said she’s seen firsthand the effects of gender roles.

Reis, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Hispanic Languages and Literature, recounted an experience she had at a conference on African literature that demonstrated internalized gender norms. Reis said a few of the women told her “How can you not cook? Many young men are going to return you to your parents because you don’t know how to cook.”

Reis spoke at the Wednesday afternoon panel “What is Justice?: Contemporary Perspectives on Global Feminisms” that was hosted by Pitt’s Global Hub. The panel — which was organized by graduate students Christina Ong, Alannah Caisey and Karen Lue — focused on the current socio-political climate, transnational feminism, anti-Blackness and global social justice issues. Kari Kokka, an assistant professor of mathematics education, moderated the discussion.

But Reis said this cycle of enforcing societal gender norms isn’t initiated by women. She said it can be attributed to misogyny and colonialism within education and the media.

“It somehow leads you to certain beliefs and certain behaviors that doesn’t mean that you initiated those behaviors, you’re repeating them for a certain reason,” Reis said. “There is a cycle that sometimes you see that women continue this different treatment with daughters and sons, and even the concept of dividing between the two that is rooted in colonialism — the creation of different kinds of hierarchies and inequalities.”

The panelists also discussed the concept of feminism through a more global lens. Jessi Hanson-DeFusco, an adjunct professor and visiting scholar in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, said she sees global feminism as a “united sisterhood” that brings women together.

But she said it is also crucial to acknowledge that the definitions and context of feminism, oppression, gender exclusion and gender-based violence can vary among people in different parts of the world.

“We do have to realize that a lot of the definitions that women and people who feel themselves as women experience can be different,” Hanson-DeFusco said. “And we have to be very careful and have a dialogue about those definitions, and not define them for people but with people.”

To address the wider concepts and definitions of feminism, the panelists also focused heavily on intersectionality. Anna Carastathis, a political theorist and co-director of the Feminist Autonomous Centre for Research, said intersectionality is broad. She said it’s the idea that systems of oppression such as racism, sexism and homophobia are intertwined.

“Intersectionality refers to how people who experience multiple forms of oppression are systematically rendered invisible by social theories and social movements that focus on one system to the exclusion of other systems,” Carastathis said.

Carastathis referenced political scientist Amrita Basu’s research article when talking about the history of global feminism and intersectionality, allowing for the feminist movement to transcend borders. She also pointed out that the concept of intersectionality is one that originated with women of color and Black feminst theory in the United States as a way for Black feminists to call out the “social movements that sought to exclude and subordinate them.”

The panel also had a lively discussion on the definition of feminism and what it means to be a “feminist.” Vivetha Thambinathan, an Eelam Tamil activist and doctoral candidate at Western University, said she doesn’t like to identify as a feminist because the term is commonly associated with upperclass white women.

“Historically and politically there’s a lot of identity lifestyle that’s connected to what a feminist is, that for me myself I feel that it takes away from me identifying as a feminist,” Thambinathan said. “Dr. Angela Davis has recently called this ‘glass ceiling feminism,’ where only the people at the top, who are usually white women, or if women of color then affluent, all they need to do is just break the ceiling because they’re already higher up in the ladder.”

Thambinathan added that she prefers the phrasing — coined by social activist and author bell hooks — “advocating for feminism” rather than identifying as a feminist.

Carastathis said feminism has been used by “radical feminists,” who have regressive views about race, gender, sexuality and social justice, to exclude trans and nonbianary individuals from having roles in feminism movements.

“It’s an old and tired and leads to nowhere debate about whether or not trans people ought to be seen as agents of feminism, which has never led anywhere and is nothing more than transphobia, from my point of view,” Carastathis said.

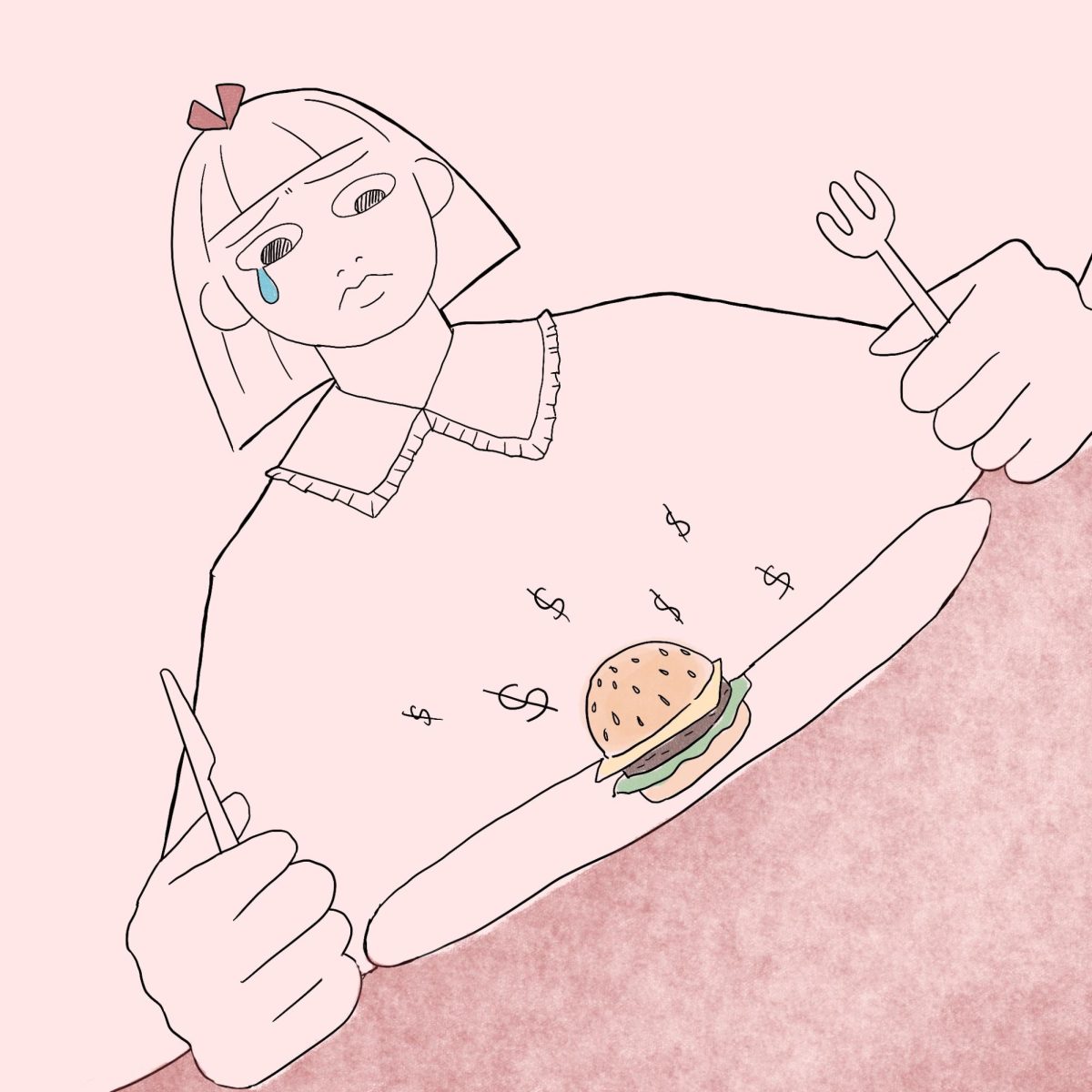

Reis ended the event by describing an image of equity versus equality — where three kids are trying to watch a baseball game but there’s a fence in front of them. She used this image as a metaphor for her goal of feminism free from systems of oppression.

“What I really want is the wall, to completely break down that barrier to be destroyed. I don’t just want this bigger box so I can access and see it,” Reis said. “So I want that wall to be destroyed but until the wall is destroyed, until that barrier is completely taken out. I’ll take the box. But we cannot stop at this box, we need justice.”