Op-Ed | Why I Oppose Unionization: An Open Letter to My Colleagues

August 24, 2021

This Op-Ed is part of a series about faculty unionization. To read the Op-Ed in favor of faculty unionization, click here. For information about the faculty unionization election, click here.

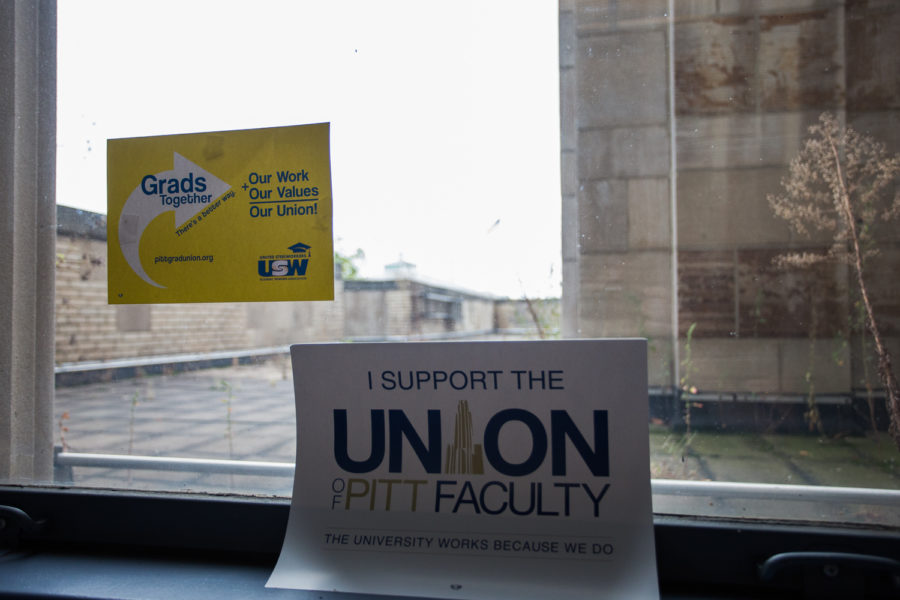

As you may have heard, beginning on Aug. 27, faculty will be voting on whether or not to form a union and affiliate with the United Steelworkers. This is a significant decision point in our professional lives, and it is important we make our decision based on facts and what will best allow us to continue to do our work both now and in the future.

After much thought and consideration of the evidence, in my judgment unionizing and affiliating with the United Steelworkers is not in the best interest of the faculty at Pitt. I write from my perspective as a tenured professor in the Department of Political Science — my views do not represent any of the shared governance institutions at Pitt, though my service as president of the University Senate and other instruments of shared governance have informed my position on unionization.

At the outset, I want to state that I am the product of a union family. Indeed, both of my parents were members of an education union. I have lived both the positives and negatives of unions. Moreover, I believe unions have played a vital role in the economic and social life of this country. Like most things, however, this recognition does not mean that unions are always a positive force or the right decision for Pitt faculty at this time. Why do I oppose unionization?

- Very few AAU schools are unionized. For a reason.

When we look at our peers, as best I can tell, only 5 of the 63 AAU universities in the U.S. have faculty unions that have the power to engage in collective bargaining agreements for tenured and tenure-track faculty. And of those five, only two, Rutgers and Florida, are ranked similarly to Pitt.

While this in itself is not dispositive, it does suggest that we should ask why that is the case. The reason is straightforward — at research intensive universities, the duties and responsibilities of faculty are so diverse that there is not a shared “community of interest.”

Union organizers implicitly acknowledge this — their documentation has lots of support from institutions that have different missions from Pitt, and none from places we consider our peers or aspirational peers. To recruit and retain excellent faculty who are performing cutting-edge research, Pitt needs to maintain maximum flexibility, something our peer institutions recognize.

Indeed, a 2016 report by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that faculty with greater research productivity are less supportive of unionization and “this raises the possibility that universities that organize will face difficulty attracting and retaining the most productive scholars.”

- We have a strong system of shared governance.

I agree that faculty should have significant say in the conditions of their workplace. Our system of shared governance already provides this. Faculty have representation on every University committee as well as Board of Trustees committees. Faculty involvement in the development of policies have led to significant improvements on such topics as intellectual property, sexual harassment, academic freedom and more. Additionally, through the University Planning and Budgeting Committee, faculty are highly involved in recommending the University budget every year as well as setting the salary pool.

As someone who was initially a vocal skeptic of shared governance — thinking it was merely a mechanism for faculty to act as “yes people” for the administration — but who has been intricately involved in shared governance over the past few years, I can also say that there have been several instances where we have been able to work behind the scenes to prevent things from even coming up publicly.

Another success is the improvements that have been made for faculty outside the tenure stream. In recent years, Pitt has moved to multi-year contracts, establishing a clear promotion path, and introduced compensation in the event of last-minute class cancelations. All of these items have been accomplished within our system of shared governance. (And, I hasten to point out, without the help of most of the faculty who are members of the union organizing committee.)

- Unionization sets up an adversarial relationship among our colleagues.

The decision to unionize stands in sharp contrast to a system of shared governance. This sets up an “us versus them” dynamic among faculty that can be very harmful in the academic setting — indeed, it is the exact antithesis of shared governance. Along these lines, it also pits faculty who are temporarily serving in administrative roles, including department chairs, against those who are not — most members of the administration have exemplary records of academic scholarship and distinguished teaching, and continue to have a “home” department.

Instead of all faculty — administrators and non-administrators — working toward the same goals, there will now be two distinct camps, each of which is trying to “win” things from the other. If we did not have a strong, robust system of shared governance, this might be a cost worth paying. But we do. And we have been able to accomplish, or are on our way to accomplishing, many of the union’s priorities in a collaborative, rather than adversarial, process.

- The proposed bargaining unit is so big as to be meaningless.

The union has proposed a bargaining unit that includes all part-time and full-time faculty, except for the medical school. (Of course, successfully fighting for the exclusion of those colleagues calls into question the union’s mantra that it wants to be a union for all faculty.)

However, this proposed unit contains so many different faculty positions that it is unclear what a fair contract would look like. Tenured and tenure-stream faculty members on the Oakland campus have different jobs than tenured and tenure-stream members at the regional campuses. Part-time and full-time appointment-stream faculty members have different jobs and responsibilities than tenured and tenure-stream faculty members.

Simply put, it is not true that appointment-stream faculty have the same duties and expectations as tenured and tenure-stream faculty. This is not to say the work any particular group does is better or worse, or that one is more or less valuable— it is just different. There is a reason why very few faculty unions at AAU universities lump every faculty member into one group — indeed, there are several AAU universities that have appointment-stream and part-time faculty unions, but not tenured and tenure-stream.

- The Janus decision significantly changes the landscape in a way that makes unions less effective.

After the Supreme Court’s decision in 2018 in Janus, unions can no longer compel an “agency fee” for non-members. This means that people covered by a collective bargaining agreement cannot be forced to either join the union or financially subsidize their activities.

This means it is going to be exceptionally challenging for the union to recruit members. A weak union, one that does not have the support of the faculty either in terms of membership or finances, will leave all Pitt faculty members significantly worse off. Since the decision to join the union will be made by a simple majority of those voting, it is possible that 5% or 10% of highly motivated faculty — some of whom only teach a class or two per year — will commit the rest of the faculty to a union since individual faculty members cannot opt out of the bargaining unit.

And there is no reason for faculty who do not support unionization, who may be a majority of all faculty members, to financially support this decision. This has real consequences for leverage. Recently, the faculty at Wright State went out on strike for 20 days. The union at Wright State — which is affiliated with an academic union, unlike the effort on our campus, which is affiliated with the Steelworkers — had 560 members out of 1700 faculty. That is, about two-thirds of Wright State faculty were not members of the union.

It is not much of a surprise, then, that not only was the strike long lasting — due to the lack of union leverage — but also, at the end, the union president admitted that the faculty there took a financial hit, both long- and short-term.

- The United Steelworkers has little experience with faculty unions.

Despite the language on the Pitt Faculty Union webpage, the USW does not have a significant footprint in the education arena. The Pitt Faculty Union website refers people to the Academic Workers Association. Yet, the website linked from their Facebook page no longer exists!

Prior to this, there were only two organizing success stories listed — Point Park and Robert Morris universities. Both of these efforts were for part-time faculty only. Also, the language that the Pitt Faculty Union uses is “academic workers,” not faculty members.

As far as I can tell, there is simply no evidence that USW has successfully organized any group of full-time faculty. Moreover, it appears from the USW website that faculty and graduate students at Pitt are the only clients the USW has.

Given this lack of experience and expertise, one must question how effective the USW will be in understanding the workings of academia and assisting in the negotiation of contracts. Additionally, the USW recently failed in their attempt to organize Pitt graduate students, and the Pennsylvania Labor Relations board rejected claims that the election was unfair.

- All groups involved are self-interested and there are alternative ways to obtain the same outcome.

There has been much stated about how joining the union is the only way to have any say over working conditions, and that faculty leads and will run the union movement. Yet, the USW is not expending significant material and financial resources — no one will disclose how much this effort is costing the USW, though a tweet by one of the Pitt organizers suggests it is in the millions — in this movement out of beneficence.

They also have a financial stake in its success. Specifically, this is an opportunity for them to expand their membership and increase their revenues. It is a new sector for them as well. We should ask, “Why the USW? What’s in it for them?” The answer is that this is a way for them to make money and grow their organization.

Some of the dues faculty pay will go to the USW and we will not have control over how that portion is spent. Moreover, if we look at the size of recent salary raises at Pitt, they have been about 2% a year. So, in order for unionizing to be financially worth it, raises would have to be at least 3.5% per year, based on the 1.5% dues that have been publicly discussed. Anything less than that will leave union members worse off financially, which raises the issue of why anyone would join in the first place.

Since unions cannot exclude non-members from the collective bargaining agreement, those who are most concerned about salaries have a large incentive not to become members — they can take the 3.5%, or whatever the increment is, and pay $0, thanks to Janus.

- Unions have a history of problematic workplace behavior.

The United Steelworkers are no exception to this. Fortunately, government reporting requirements allow one to see how many unfair labor practice claims members have brought against the union. You can find some of this information about the USW here, along with executive compensation, petitions for union decertification, etc.

Interestingly, less than 17% of their spending was on “representational” activities in 2019. The National Labor Relations Board also has a list of almost 500 labor actions since 2015 involving the Steelworkers, and also lists the nature of the allegation. If the faculty decides to affiliate with the United Steelworkers, this gives us a sense of some of the issues that may arise from that affiliation.

- Working conditions involve more than salary.

It is true that faculty salaries, especially at the assistant professor, lecturer and instructor ranks, lag behind our benchmarks of being at the median of public AAU institutions. However, working conditions and compensation involve more than just salary.

For example, health insurance is high quality, affordable and available to all full-time faculty members as well as regular part-time faculty members. For those of us with children, the tuition benefits and the tuition exchange program are benefits that not all public AAU institutions offer. The retirement program offered at Pitt is also extremely generous, both compared to other public institutions as well as compared to many private institutions.

Indeed, the 2019 COACHE survey indicated very high levels of satisfaction with the health and retirement benefits we receive. While salary is the most visible form of compensation, and we should continue to ensure that all faculty members are fairly paid for their work, faculty compensation is broader than salary.

But, even focusing on salary, it is far from clear that unionized faculty are paid better than non-unionized faculty once one takes into account measurement error, cost of living and estimates of the appropriate statistical models. Indeed, Cain (2011) writes, “The most recent evidence indicates that there is no statistically significant gain in average faculty salary for unionized faculty in four-year institutions, though there is for faculty in two-year institutions (Hedrick et. al., 2011; Wickens, 2008). Some union leaders are among those who admit that there is no union wage premium (Nelson, 2011) and some research has pointed to a slightly negative effect on wages at public research universities (Ashraf & Williams, 2008).”

- The COVID-19 pandemic shows our current system is effective.

One of the most frustrating things, to me, is the claim that if we only had a union at Pitt, faculty would have more of a voice at the table. There is simply no evidence this is true, and the COVID-19 pandemic shows how we do have such a voice.

For example, faculty leaders were able to ensure that faculty members would not need to return to campus, no documentation necessary. Faculty leaders were able to ensure that there were no layoffs or furloughs during this time, and sat on all of the decision-making bodies that made decisions.

Now, let’s contrast that to some institutions with unions. Close to home, despite being unionized and having the union object to layoffs, Point Park is in the process of significant reductions in faculty. Our colleagues at Rutgers are unionized, but they also incurred layoffs and a pay freeze despite their contract. Our colleagues at Ohio University are also unionized, yet that didn’t stop significant layoffs. At Florida, one of the few R1s with a unionized faculty, the administration forced faculty back into the classroom. And what is striking about our unionized colleagues at the University of Oregon is that they are dealing with the same issues we are —with the exception of salary cuts, which we did not have — but much less effectively, it seems.

Finally, some have been trumpeting the new Rutgers contract, which provided for a no lay-off provision through January 2022 as well as a prohibition of a “financial emergency” declaration until 2022. In return, faculty agreed to a 0.5-one day a week furlough through June. Interestingly, at Pitt, we have had no layoffs, no discussion — let alone declaration — of financial emergency, and no furloughs. Why not? The cooperation between faculty and administration and working toward common goals in a non-adversarial manner. The “gains” achieved by Rutgers faculty would be losses if the same contract applied to Pitt faculty.

In all of these cases, our shared governance system has ensured better working conditions for our colleagues than unions were able to secure. Pitt faculty are in a better position than our unionized colleagues in all of the above situations.

It is extremely important that you inform yourself of the facts and issues at stake in this decision. As we learned from the previous PLRB ruling, the union barely had enough signed cards from 30% of the faculty necessary to trigger an election. If they had a majority—or even close to it—their petition for an election would not have been initially denied.

The decision over whether the USW represents us will be made by a majority of those voting. Thus, 50% of 30% can make a decision that will be binding on us all. Given that those supporting unionization will be highly motivated, those who oppose it cannot simply sit this one out. Supporters have a well-funded operation to generate votes, while the opposition tends to be much more diffused and unorganized simply by the nature of the process.

In closing, I encourage all faculty members to inform themselves about the pros and cons of unionization. This is a decision that could fundamentally change the nature of faculty life here at Pitt. Our current system of shared governance is not perfect, and we are continually working to strengthen it. We need to continue to work collaboratively to advance both the interests of the faculty and the mission of the University.

Bonneau served as University Senate president from 2018-21. He is a political science professor.