‘Fear Street’ screenwriter explores queer horror with Horror Studies Working Group

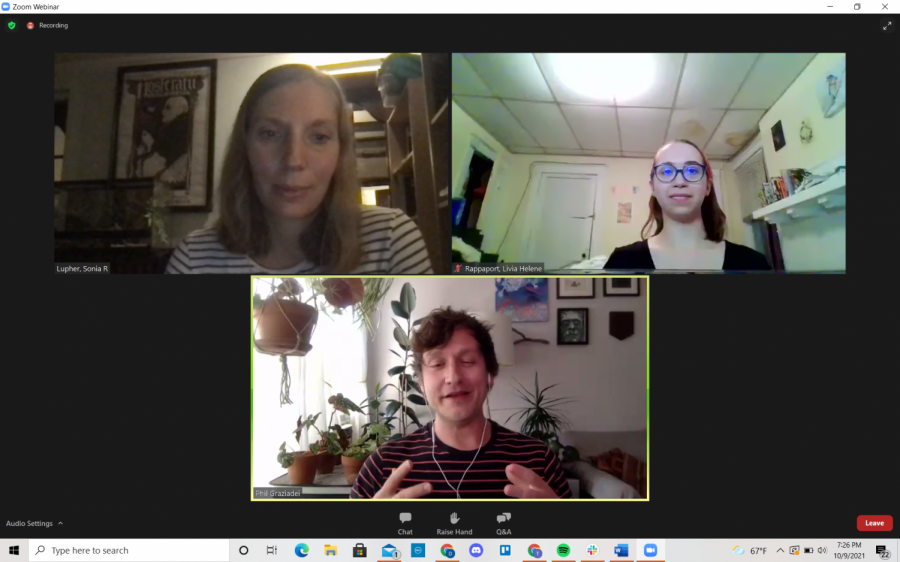

Phil Graziadei (bottom), the screenwriter behind Netflix’s hit “Fear Street” trilogy, gave a talk this Saturday with Pitt’s Horror Studies Working Group about his work in horror film and the explicit queer themes of the Netflix movies.

October 12, 2021

Queer influence in the horror genre extends far past the bounds many people initially think — lingering in classic works such as Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” according to screenwriter Phil Graziadei.

“The sort of connection between queer themes and the horror is at least as old as Shelley. It’s at least as old as original Frankenstein, a book written by a bisexual woman,” Graziadei said. “Self-identified, or at least, openly talking about the way she thought about pursuing relationships with women after Percy died.”

Graziadei, the screenwriter behind Netflix’s hit “Fear Street” trilogy based on the books of the same name, gave a talk this Saturday with Pitt’s Horror Studies Working Group about his work in horror film and the explicit queer themes of the Netflix movies.

The trilogy focuses on the lives of teenagers living in “Shadyside,” a town plagued by a series of repeated brutal murders starting all the way back in the 1600s. Each film takes place in a different time period — 1994, 1978 and 1666.

Graziadei said the trilogy was filmed all at once, initially under 20th Century Fox, with the intention of releasing them theatrically. Netflix bought the rights to the trilogy in 2020 and released them each a week apart this past summer.

This was Graziadei’s first time working on a major studio production. He previously worked with “Fear Street” director and co-writer Leigh Janiak on the indie-horror movie “Honeymoon,” starring Rose Leslie. He said having a close relationship with Janiak, who he’s known since his days as an undergrad at New York University, allowed for a more casual and seamless experience working on the film.

“In independent film, you generally have a little bit more control. I think that my experience is probably a little bit different from most writers working within the studio system, because my writing partner is also the director,” Graziadei said. “The director is basically the king or queen in those situations.”

Sonia Lupher, associate director of the Horror Studies Working Group who also moderated the talk, said she was pleasantly surprised by the explicit queer themes of the films, particularly the relationship between the two stars Deena (Kiana Madeira) and Sam (Olivia Scott Welch) which all three films feature.

“I was really pleased because I feel like [their relationship] is kind of set up as a twist, in a way. Like in the first film, you feel like Deena is watching the guy, right? You think Sam will be the guy,” Lupher said. “So it’s set up that way, I think on purpose, and then it very quickly normalizes their relationship.”

Grazaidei said the decision to make those characters queer was very important to him and Janiak early on in the script process. They were pleasantly surprised with support from the trilogy’s producers and Netflix, which Graziadei said is still unfortunately rare for large productions in Hollywood.

“They were very supportive. From the very beginning, in that respect. Which is a big deal. It’s a really big deal,” Graziadei said. “I will say that in general, it’s really hard in Hollywood to get queer content made a major studio level. There are very few places that are willing to do it or invested in doing so.”

In the original “Fear Street” books, written by R.L. Stine of “Goosebumps” fame, there were no explicitly queer characters. But Graziadei said the fan community often catalogs what they see as homoerotic subtext in the novels, of which there are more than 100.

“There are all these like fan blogs, I think Welcome to Fear Street is one of them, where they catalog cultural trends,” Graziadei said. “And one of those categories that they put together is homoerotic subtext. Most of the books are about teenage girls. And there are a lot of body image issues and obsessions between your cheerleader rival from another school or something like that.”

Though fans might be able to find queer themes or subtext in horror films or books going back to the late 1800s, it’s not a substitute for clear representation. Livia Rappaport, a senior film and media studies major and a member of the Horror Studies Working Group, said she liked how Graziadei acknowledged both the queer “monstrous” subtext and obviously queer characters.

“I liked how he acknowledged how there’s nothing wrong with the narratives about embracing one’s “monstrosity” that we often see, but that it’s important to show queer people not as monsters at all,” Rappaport said.

In horror and other genres like science fiction, queer characters are almost exclusively shown or alluded to in a “monstrous” form. Whether that’s with early iterations like Frankenstein, ‘90s movies like “Poison” and “Silence of the Lambs” or more recent media like “Jennifer’s Body” or “Hannibal.”

While Graziadei said these kinds of depictions have value, it’s also very important to depict queer characters in happy storylines and lives, without a cloud of “other” following them.

“But I don’t see myself as a monster. And generally, when I do see myself as something monstrous, it’s not related to my being,” Graziadei said. “I think it’s okay for queer storytellers to examine the extent to which they’re seeing themselves through their own eyes, and not through society’s eyes.”

According to Lupher, part of what the Horror Studies Working Group does is emphasize the emerging group of filmmakers who are from or who highlight marginalized groups, such as members of the LGBTQ+ community.

“This is happening in terms of race and gender as well, not just sexuality. So all sorts of things nationally,” Lupher said. “We’re seeing a lot of new horror films coming out, a lot of new takes on sort of classic tropes and things like that.”

Graziadei said “Fear Street”’s happy ending for its queer protagonists is an anomaly in horror, even today, and he hopes the movie sets a trend in the future for queer characters in the genre.

“And what we did in ‘Fear Street’ is something that hasn’t been done in 100 years of horror. I hope people will enjoy these movies,” Graziadei said. “And I think they have done well so far. So I hope there’s more room moving forward. For more positive representations for queer people in horror.”