‘New level of understanding’: Pitt celebrates world GIS day

Ruth Mostern speaks at a Pitt event on Tuesday about historical maps celebrating Geographic Information Systems.

November 17, 2021

By moving a stone on his property, a Belgian farmer accidentally moved the border between Belgium and France in May 2021. Ruth Mostern said situations like this show how maps have a relationship with the real world.

“The world creates the map to be a certain kind of way,” Mostern, the director of the World History Center and faculty member in Pitt’s history department, said. “And also the map recreates the world. That dialectic between the map and the world is the first and most intriguing question to ask about historical maps.”

Pitt celebrated World Geographic Information Systems day, which is on Wednesday, by hosting a Tuesday webinar on Zoom about historical maps and how to digitize them. GIS day celebrates GIS technology, which helps gather, visualize and analyze geographic data, according to GISday.com. Three keynote speakers presented at the event — Mostern, Susan Grunewald, a postdoctoral fellow in digital world history, and Kathy Hart, a WHC research affiliate.

According to Grunewald, there are two main ways of using GIS that are both quite simple to use — desktop-based software and web-based software.

“Georeferencing is a really easy thing to do,” Grunewald said. “All you need is an image file of the map you want to georeference and you upload it onto the GIS software and line up the image with the control points on the coordinated map. It is as simple as drag and drop and double clicking.”

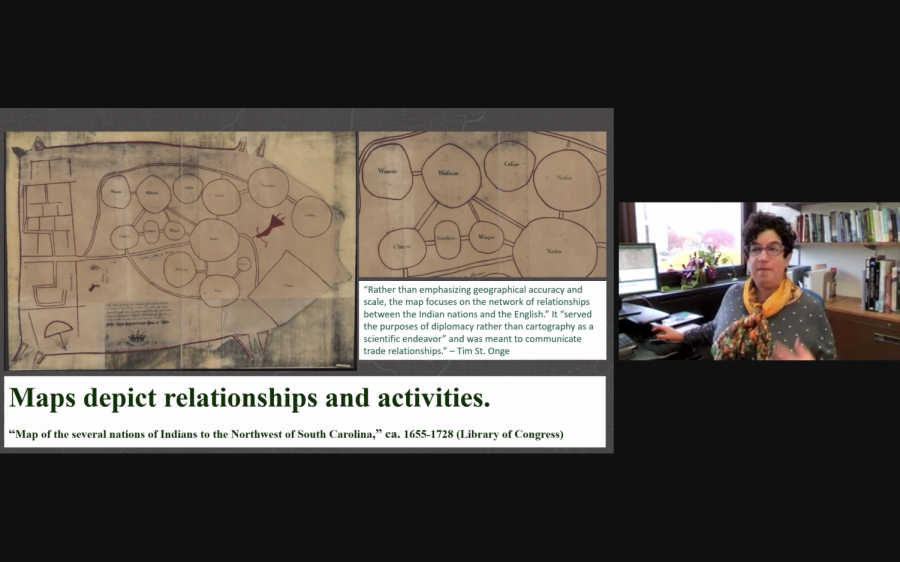

Mostern said every map is biased based on the cartographer who designed it, and these biases stem from the year and location that the cartographer lived in. Mostern said maps can display historical relationships and trade, not just geographical locations.

“What I really love about historical maps is that the relationship between the map and the world is so complex,” Mostern said. “The map does not transparently represent the world, but on the other hand the map is not unrelated to the world either.”

Hart explained where to find historical maps and how to understand them, such as the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection and the Library of Congress Digital Map Collection. She said one of the best parts of GIS technology is that it helps historians understand where many historical events occurred.

“When you use historical maps for their own purpose but also for GIS, it just brings a whole new level of understanding,” Hart said. “GIS helps in many ways but particularly [with the] ‘where.’ Where things happen is critical to knowing how and why they happen. We cannot separate the historical event from where it happened.”

Hart said these maps convey more than geographic information through their characteristics such as color, legend and scale. She said by analyzing historical maps, people can discern what they are conveying politically or socially.

“A close read with literature is a deeper level of reading and analysis and we can do the same thing with maps,” Hart said. “The whole point is to dig deeply and study small areas and make sure we understand the intent of the map. Do we understand the legend and what the colors and labels mean? Do we understand the time period this map was made, were the biases either political or social.”

Hart also said the prime meridian, north arrow, compass rose, cartouche and scale on historic maps may change throughout history. For example, many maps may be rotated so their north arrow points another direction.

“We know the prime meridian is an imaginary line, it’s the starting point for measuring east and west but it is arbitrary,” Hart said. “It was not until 1884 that it became a standard, internationally agreed upon line in Greenwich, England. Prior to that France used Paris as its prime meridian, the Chinese used Beijing.”

While these discrepancies in historic maps exist, Grunewald said GIS software can “georeference” these maps by overlaying historical maps onto map interfaces such as Google Maps.

“Once we have a historic map and we can read it, we can georeference it,” Grunewald said. “A map is just a picture, there are no geographic coordinates assigned to it at all. With georeferencing you’re looking for points on your image and lining it up with a mapping system that has coordinates there.”

Hart said studying these maps is important because they reveal so much about historical biases and politics.

“Historical maps have fallen out in modern day, we don’t really think much about what modern maps convey,” Hart said. “With historical maps what they are trying to convey is so important. What these maps show reflects the bias of the cartographer.”