Pitt professor talks new book, class disparities and Black women’s literature

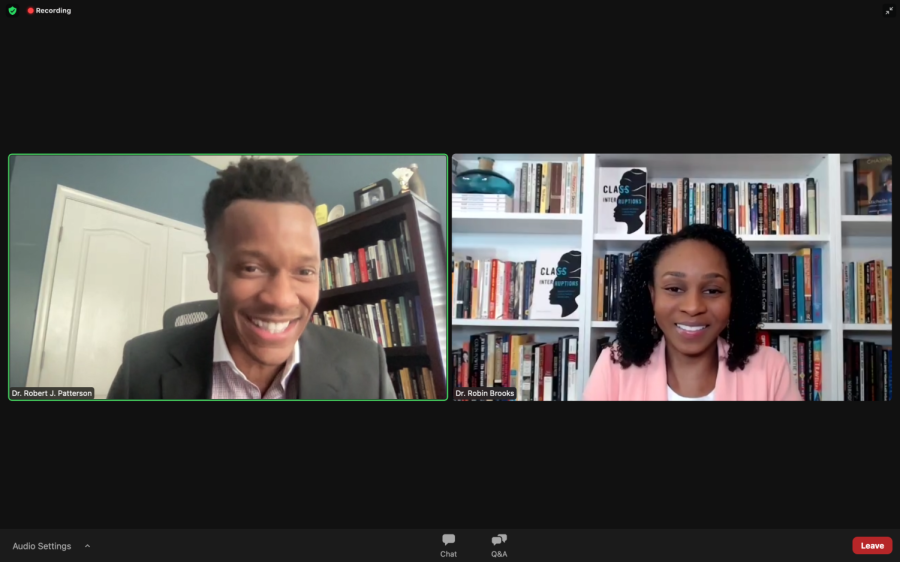

Robert Patterson, left, and Robin Brooks discuss Brooks’ new book “Class Interpretations: Inequality and Division in African Diasporic Women’s Fiction” at a Tuesday Zoom event organized by the African Studies Department and the University Library System.

February 3, 2022

For Robin Brooks, her new book “interrupts” the lack of scholarship about class and class divisions in creative writing. Brooks, an assistant professor of Africana Studies at Pitt, said creative writers often discuss class in their works, but the topic often goes unmentioned in academic settings.

“I emphasize scholarship because one thing that my research shows is that these literary artists have long been discussing class in their creative writing,” Brooks said. “It’s just that the scholarship on this creative writing has not kept up, and so this interruption is trying to interrupt inequalities in order to hopefully destabilize an unjust status quo.”

The Africana Studies Department and the University Library System held an event on Tuesday on Zoom to discuss Brooks’ new book, “Class Interruptions: Inequality and Division in African Diasporic Women’s Fiction.” The book talks about how Black women’s literary works — including contemporary works by African American and Caribbean writers such as Toni Morrison and Olive Senior — cause debates on the growing income and wealth gaps globally in the late 20th and 21st centuries. Robert J. Patterson, a professor of African American studies at Georgetown University, led the discussion.

Patterson said one of the key points to this discussion of class is intersectionality — the interconnections of race, sexuality, gender and class as they apply to an individual. He said the book explains how class is not discussed enough in conversations about intersectionality, and Brooks uses literary works to emphasize this.

“I think one of the important points that you draw forth is how class, right — an intersectional model — doesn’t always get pulled out as much as you think it should, and so you try to do that and do it well across the diasporic women’s cultural production,” Patterson said.

Brooks said her book highlights class to show different aspects of intersectionality.

“Intersectionality is very much so central to this book,” Brooks said. “Intersectionality is key, but what my book does is it emphasizes class in order to show the many dimensions of the Black feminist theory of intersectionality.”

Patterson asked Brooks if her research led her to interest in topics she was unable to cover in her first book, but she’d like to write about in the future.

Brooks said because of her research on class disparities, she became interested in “economic injustices concerning environments.” She said working class neighborhoods experienced more garbage dumping and pollution than wealthier areas, which then leads to health problems for people living there. Brooks also said environmental racism and environmental injustices are “definitely connected” to class issues.

“I recognize that all over the world, we see working class neighborhoods literally being treated as if they are garbage pails where you have societies literally dumping pollutants and other garbage,” Brooks said. “It’s leading to things like health challenges, increases in cancer, premature death, developmental delays with children … I did not discuss this in this book, but it’s an interest that this book has certainly led me to.”

When asked about her next project, Brooks said her second book will focus on the “life writings” — memoirs and autobiographies — of African Americans, as well as “Black death.” She said much like class, death has played an important role in her life.

Lisa Brush, a professor of gender, sexuality and women’s studies at Pitt, asked Brooks how Erik Olin Wright, a professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, influenced her research for this book. Wright, whose work focused on class analysis, passed away in 2019.

Brooks said Wright’s work from his book, “Class Counts,” was “foundational” to her research for her book. Wright’s book covers research on topics including class mobility, friendship patterns of different classes and class consciousness.

“His work was actually foundational to what I’m calling that cross class relationship trope … he found that the most permeable boundary for people to cross in terms of being friends is the boundary between working class people and middle class people,” Brooks said. “His scholarship really supports the claim I made concerning this literary trope that the majority of the relationships that you see that are cross class are between working class characters and middle class characters.”

Brooks said her book was written for anybody who wants to learn more about class inequalities and how these issues affect people around them.

“I want people to pay more attention to the role of class in people’s lived experiences,” Brooks said. “I want people to stop shaming people for things that really stemmed from structural inequalities. So anybody interested in this, this book is for you. It was written for you.”