Opinion | After the Ukraine War, Europe owes the U.S. a commitment to democracy

Children look through car windows as they and other refugees from the Kharkov Region of Ukraine arrive at a temporary camp in Belgorod, Russia.

October 12, 2022

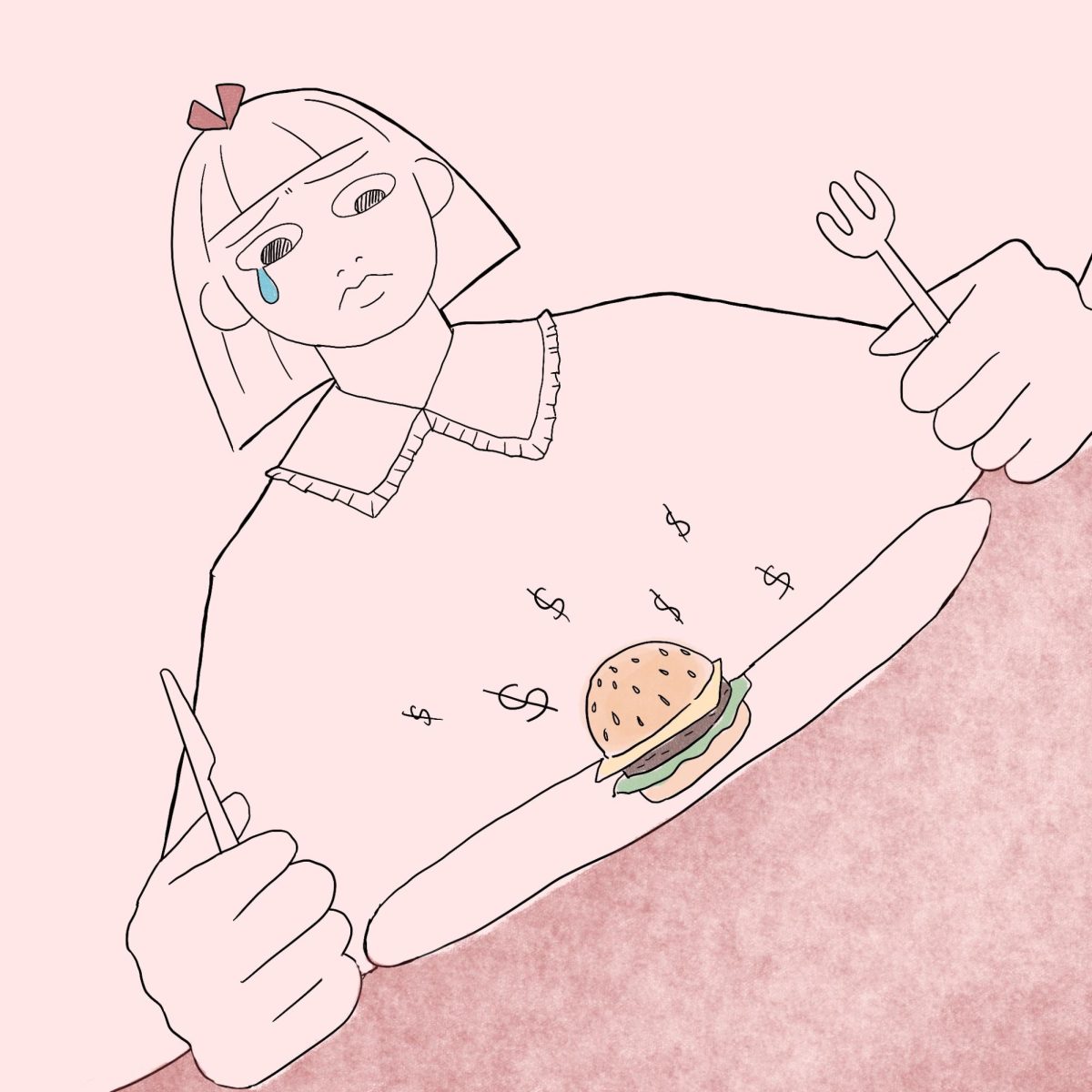

American money — whether it be real dollars or loans to Ukraine — is at the center of the Ukraine-Russia conflict that has been ongoing since February.

From January to August 2022, the United States has committed more than $42.7 billion to Ukraine through military, financial and humanitarian aid. This commitment is almost triple that of the European Union, the next largest contributor, whose territory is most at stake during this conflict. The additional aid comes during a summer of record high gas prices for American citizens, in part due to America’s commitment to sanctions on Russian oil.

In recent weeks, American citizens are changing their minds on supporting the war, mostly driven by their wallets. Recently, 58% of Americans say they somewhat or strongly oppose continuing the current trend of aid to Ukraine if it means that they will be affected at the pump or grocery store. Even if the American people are not losing their income to support Ukraine, such as through taxes like in other European states, American aid should come with reciprocation.

This reciprocation does not necessarily have to be economic. It can also be political. Europe can affirm its support to the U.S. by investigating the democratic backsliding that is currently sweeping through the continent.

Speaking in Poland in March, President Joe Biden referred to the Russian war as a strangle on democracy, calling Russia autocratic. In recent weeks, Biden has been clear — the war in Ukraine is a struggle between democracy and authoritarianism. If Biden’s rhetoric is trustworthy as the real reason for our overwhelming financial support to Ukraine, then he must pressure the EU to reciprocate by affirming their commitment to democracy as well.

The American people are financially supporting this war in the hopes of keeping democracy alive globally, so Europe must better police its own backsliding democracies.

The best place for the EU to start making meaningful progress is in Hungary. From the outset, the most recent Hungarian election seemed to be functionally democratic. But this image falls apart when looking further. The state government is allowed to use its own resources in the media to prevent the spread of opposition campaigns and bolster its own campaign. A report from the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights found during an investigation that the lines between party and government became so blurred that the voting choice felt unfair.

In the most recent election, Viktor Orbán’s amendments to the constitution and gerrymandering of Hungary worked yet again, giving his party far more representation than deserved. At the most recent Conservative Political Action Coalition conference in the U.S., Orbán was a guest speaker following his recent racist remarks and subscription to the white supremacist “great replacement” theory. This idea posits that an influx of immigrants from other nations is detrimental to keeping a white majority in any nation and must be stopped.

Furthermore, Poland has come under fire for diminishing EU values of democracy as well, and Italy has been criticized for recently electing the far-right Giorgia Meloni.

The EU has let these nations’ democratic backsliding go too far unchecked. In an ideal world, Biden could withdraw his administration’s support for European safety in Ukraine or other non-NATO nations on Europe’s doorstep by demanding that the EU remove the backsliding regimes from the economic bloc. There is a simple flaw with that thinking, though — the EU does not have a system in place to remove a member nation, and now that Hungary, Poland and Italy feel the disapproval of the EU growing, it is unlikely that they would let an amendment like that pass.

Polls state that in Hungary, EU support is still a majority. It’s a shame that the EU cannot leverage this support against Hungary by threatening to remove it.

The EU has blocked funds for economic relief to Hungary, along with creating a new set of sanctions. The EU ought to use these new sanctions to completely block Hungary from receiving access to the EU budget. With pressure from the U.S., the EU could expedite processes that normally take many months to execute, such as imposing more sanctions and blocking the transfer of funds to Hungary. The U.S. could force the EU to take quick action on these issues, but only by using Ukraine as an ultimatum.

Furthermore, Europe as a continent, not just in the scope of the European Union, has a lot to offer the U.S. in terms of NATO. In short, Article Five of NATO states that individual member countries require protection from attack by all other member countries. Poland and Hungary are protected by this alliance, despite their non-commitment to democracy. Biden and Europe should threaten the formation of a new alliance without these nations if backsliding continues. The U.S. ought to signal to Hungary that its commitment to Russia economically also implies its commitment to them militarily, as well.

These actions not only would benefit the citizens living in countries facing serious democratic backsliding, but it could also provide initiative to strengthen the U.S. in the face of the same problems. As the potential second election of Donald Trump looms, the U.S. needs commitment from other nations to keep our future democracy in check, too.

Paul Beer writes about political affairs and reads too many album reviews. Write back to him (or send music recommendations) at [email protected].