Opinion | Stop making me watch women get hurt

March 15, 2023

As a woman, I’m always carrying the deadweight fear of becoming a victim of violence. To acknowledge this danger fully is nearly impossible. Occasionally, however, I let myself think about how every man I let become a part of my life could choose to end it. I might meet my death by angering a man that I thought I could trust, or by angering one who doesn’t even know me. I don’t think it’s possible to fully come to terms with this knowledge — it’s just too heavy — but I am confronted with this threat all the time since the world just loves to see women get hurt.

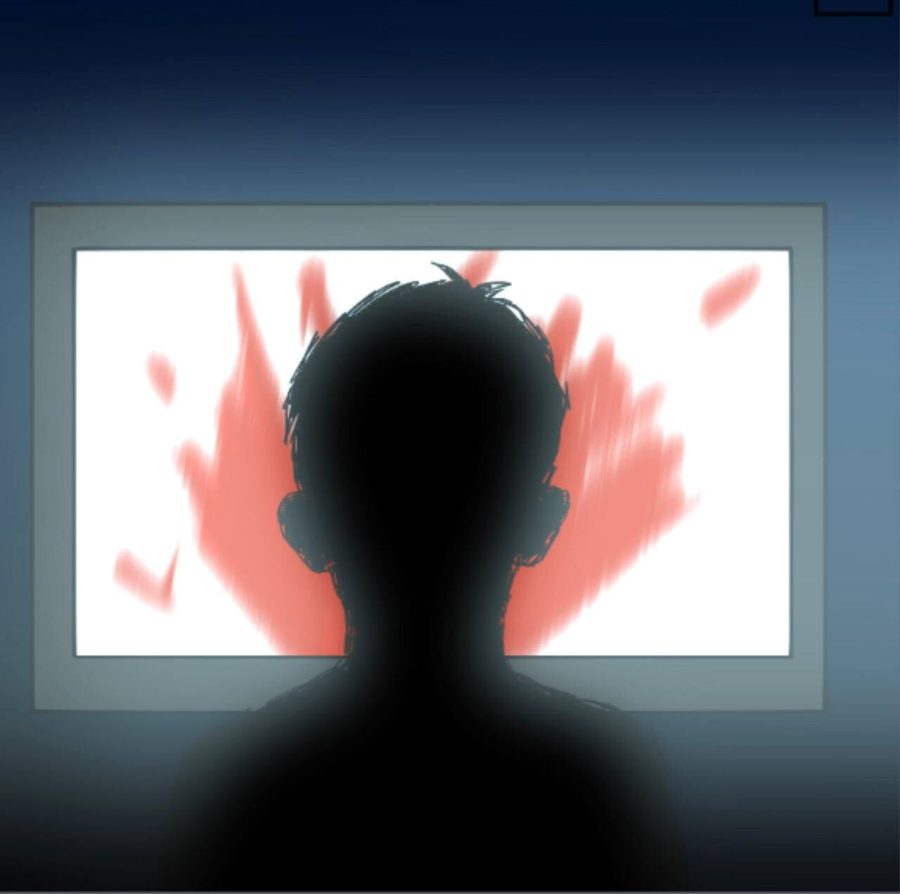

Have you ever watched a movie that feels like it’s getting off on women’s pain? Sometimes it seems that every time a woman gets hurt in a film, the director shoves it in my face. Close ups of the screams, the blood, the sadistic anger on the face of the man who did it. It’s like a reminder — “Have you thought about how you could become this victim at any moment?”

Violence in movies is quite common. Since the Motion Picture Association of America lifted the Hays Code in 1968, violence has become a staple of film, leading to the modern horror genre. I don’t necessarily have gripes with violence being shown at all, but I do wonder sometimes if violence against women needs to appear often and in as much detail as it is.

I watched a film for a Shakespeare class about a year ago which still haunts me — Roman Polanski’s Macbeth. Usually I love to watch Shakespeare adaptations since I find the adaptation process a great study, but thinking about this movie feels like pushing at a loose tooth with my tongue — a pain that I just can’t stop inciting.

In Shakespeare’s plays, almost all violence takes place offstage, even in violent events like coups and battles, since violence could not realistically and safely appear onstage. Thus, many deaths are announced to the audience after the fact, making the reaction to death much more important than how it happened. Film, however, is not held to the same limits as the stage. Camera tricks and post-production special effects can make violence appear very real on a screen. In making his movie, Polanski apparently decided that, although the story of Macbeth didn’t necessitate showing violence, it was something he was going to do anyway — and he truly took it to extremes.

As a film major, I have definitely watched my fair share of violent movies. I’ve always had trouble stomaching violence — I fought back tears as a kid after a character got stabbed in Marley and Me — but I’ve definitely built up thick skin these past few years. Despite all my experience, nothing I’ve seen can hold a flame to the relentless brutality in Polanski’s Macbeth. Gore was around every corner. Heads, arms, legs, all sorts of limbs were rolling on the ground. Blood was absolutely everywhere. Most of these terrible images I’ve managed to block out of my mind, but one moment has stuck with me, unforgettable. In the midst of a violent takeover of a castle, the offending army raped a woman.

It was in the background of a shot, like a throwaway moment, just a small detail adding to the ambiance of the scene. It felt thrown in with such a flippant, blasé attitude, as if to say “this is just how things go” — when a castle is taken over in a battle, the offending army rapes the women who happen to be inside. This is realism.

And while rape has happened in battles, that is not any sort of excuse to immortalize that image on a screen. I am traumatized from seeing that. I can’t get it out of my head. I don’t think I ever will. It felt like a threat, like Polanski was reminding me that this is what happens to people like me — we get attacked when we’re in the wrong place at the wrong time just because of the bodies we have.

Knowing anything about Polanski makes this enjoyment in women’s suffering less surprising. Polanski very famously fled the United States after finding out he faced jail time for statutory rape. Rather than facing the consequences of assaulting a 13-year-old girl, he fled like a coward and has lived in France for decades since, continuing to make films. Despite making Macbeth before he committed this assault, it all paints a very clear picture that Polanski has always been someone who enjoyed watching women — and literal children — suffer, at his behest.

And not only did he enjoy this suffering, but he also made this enjoyment available to others by putting it on the silver screen where anyone could see it. Often movies depict women’s abuse with a blasé attitude, that the audience must see this suffering to understand how terrible these women’s lives are. But any time an image of a woman getting abused is put into a film, it creates an opening for any audience member to actually enjoy that image. Not everyone watches women get hurt and feels sorry. Some people delight in it.

So if a movie actually intends to make you feel bad for the women getting hurt — to make you genuinely empathize with them — it must focus on the aftermath of the abuse rather than the image of it. The movie Women Talking, released last year, performs this with perfection. This drama, directed by Sarah Polley, tells the story of a group of women in an isolated religious colony who must decide how to reckon with the recent sexual assaults against many young girls. They must stay and fight, or flee. In this colony, almost all the women have experienced abuse of some kind, but Polley never puts it on the screen.

We only see the aftermath — the bruises, the conversations with other women, the rage in their eyes as they imagine their daughters going through the same thing — and this is the true condemnation of violence. Watching women change after what they’ve gone through and exhibit the fierce need to prevent that from ever happening again while wrestling with the love they have for the men in their lives tore me to pieces.

Polley knew the only honest way to depict violence against women was showing the way women pull together afterward. She made a movie about women and survivors, not about abusers.

Many women will face violence in their lives — as many as one in three women will face domestic violence. But violence is preventable. We cannot accept films that show cheap violence against women. We cannot allow people to enjoy the idea of causing pain anymore.

Anna writes about Taylor Swift and films she hates. You can reach her at ane45@pitt.edu.