The year was 1893, and the eyes of America were focused on Chicago and the dazzling World’s Columbian Exposition, the most lavish world’s fair to date. Looking down from the Exposition’s icon, the 264-foot tall Ferris wheel, visitors saw a glimmering “city of lights” showcasing a still-novel invention — electricity.

A Pittsburgh-based engineer is to thank for the Exposition’s most famous icon.

“Pittsburgh has long remembered its relationship with the Ferris wheel because its inventor was living here at the time,” David Grinnell, coordinator of archives and manuscripts in the Pitt Archives and Special Collections department, said.

The origin of the first Ferris wheel is one of many western Pennsylvanian stories told in the new book, “From the Steel City to the White City” by Zachary Brodt, University Archivist and Records Manager for the University of Pittsburgh Library System. The book examines the Columbian Exposition, a defining event of the late 19th century, with an entirely Pittsburgh-based focus.

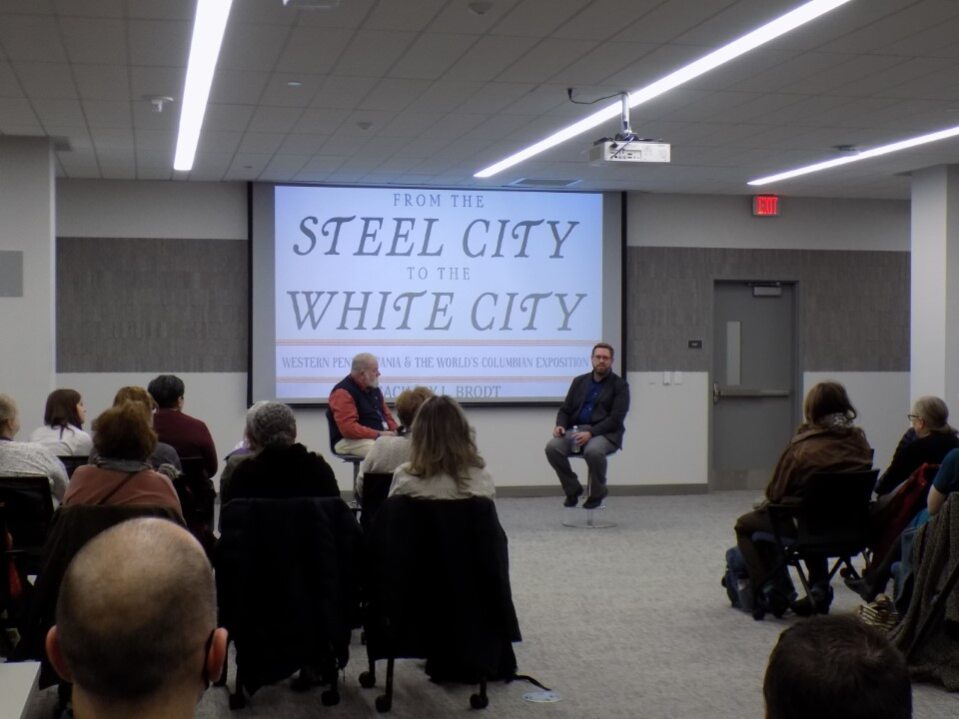

“Everything that was changing, everything that was developing in western Pennsylvania and across the country all tied into the Columbian Exposition,” Brodt said in a talk held Tuesday afternoon on the third floor of Hillman Library.

Following the 1889 Exposition Universelle held in Paris, in which the Eiffel Tower made its debut, fair planners knew they needed a memorable icon of their own for the Columbian Exposition. One partnership involving a Chicago engineer and Pittsburgh-based Keystone Bridge Company had a promising idea — a larger tower to upstage Eiffel’s.

“Everybody knew that the Columbian Exposition needed to build something better than the Eiffel Tower,” Brodt said.

Even though Andrew Carnegie was the largest stockholder in Keystone Bridge, he was less than thrilled when the press labeled the project “Carnegie’s Tower.”

“When Carnegie finds out, he’s livid,” Brodt said. “The way he sees it is that the company intentionally leaked his name as a way to get people to invest in the tower.”

With Carnegie’s lack of support, the tower deal soon fell through, and planners scrambled to find a replacement. Pittsburgher George Ferris had just the idea — a never-seen-before observation wheel, 264 feet tall, with 36 cars each the size of a trolley.

“[The Ferris wheel] becomes the icon of the Columbian Exposition,” Brodt said.

George Westinghouse, a well-known Pittsburgh inventor, won the contract to provide alternating current electricity to the fair after a hotly contested battle with competitor General Electric. Nicknamed the “city of light,” the fair blazed brightly thanks to Westinghouse electricity.

“[Westinghouse] saw it as an advertisement for himself, and he knew that it would lead to bigger and better things for him down the line,” Brodt said.

Another local exhibitor at the fair was the Western University of Pennsylvania, which eventually became the University of Pittsburgh. The University’s chancellor at the time even attended despite an unfortunate incident.

“The chancellor’s son had a firework go off and singe his face,” Brodt said. “He writes a letter saying, ‘Little Moorhead’s going to be fine, but we have to get on the train to the fair.’”

Among the exhibits of other Pennsylvania colleges, the University’s old name caused some confusion at the fair, possibly influencing the name change to the University of Pittsburgh in 1908.

“At the time they’re called the Western University of Pennsylvania, and right next door is the University of Pennsylvania exhibit,” Brodt said. “So fairgoers kept thinking that Western University was a branch campus of Penn.”

Following the Columbian Exposition, Oakland was an ideal testing ground for new ideas in urban design seen in the fair’s layout, and early Oakland buildings — including Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall and additions to the Carnegie Institute — were built with architecture made popular by the fair’s Court of Honor.

“As the Columbian Exposition is ending, Mary Schenley just donated the park a few years prior, and suddenly Oakland is open for business and ready for development,” Brodt said.

Another Oakland institution, Phipps Conservatory, brought pieces of the Exposition back from Chicago for display, forming the basis of the new conservatory.

“Phipps Conservatory takes some plants from the horticultural building out of the fair and brings them to Pittsburgh,” Brodt said. “So now there are parts of the fair sitting in Schenley Park.”

Luna Park, a short-lived amusement park in North Oakland that closed in 1909, was a direct descendent of the World’s Columbian Exposition. The park’s World’s Fair-inspired attractions made it appealing at first, said Brian Butko, director of publications at the Heinz History Center and author of “Luna: Pittsburgh’s Original Lost Kennywood.”

“Luna embraced the ‘World’s Fair’ architecture of the Exposition and kept customers there with the most recent ‘gee-whiz’ inventions and innovations,” Butko said.

However, the temporary nature of World’s Fairs was not sustainable in a permanent amusement park like Luna, and Butko says the opening of Forbes Field was detrimental to the park’s attendance. Forbes Field began a novel outdoor hippodrome that pulled visitors away from Luna Park, and the park soon closed in August 1909.

“Once people had seen the park, there was no reason to come back,” Butko said. “This forced such parks to tear down perfectly good rides every winter and build new attractions, cutting into profits.”

Although the World’s Columbian Exposition closed 130 years ago, its legacy will live on thanks to Brodt’s book, preserving the memories of western Pennsylvanian innovators who made the fair a reality.

“There are some great descriptions of people riding the Ferris wheel and seeing the White City decked out in electricity and laying before them,” Brodt said. “They called it a fairyland.”