It was like jumping feet-first into cold, clear water on an August afternoon when it happened — when the stars aligned and the Wellbutrin sloshed around in my stomach just right with some breakfast and a good night’s sleep, when I sat at my parents’ kitchen table and felt the anvil on my chest, my old friend, melt away just like that. All the misery of the past months crumpled onto the floor to join my aging dog and sprinklings of stale Christmas tree needles. I sat and I wrote and I wrote, and I marveled at the words springing forth from fingers that had been stiff for so long.

I’ve been stuck in writing purgatory for the past few months, pulled between a love of words and a vitriol for my own, a desire to do something real and a conviction that everyone would be better off if I didn’t. Not only is that kind of self-aggrandizing, it’s also obviously untrue. I didn’t hate my writing — I hated myself, and my words just happened to be the most personal output.

Yet no quantity of logical interventions from other people, no kind words about things I’d written in the past, could have pulled me out. The fog just sometimes lifted long enough to spit out the couple thousand impersonal words I needed to pass a class.

When you build your identity, even a comparatively low-stakes one like your undergraduate major, around your ability to generate a creative product, it’s terrifying to feel like you’ve lost that ability. Your friends are taking internships in New York and writing theses and submitting their poetry to literary magazines with weird names, and you’re left crying in your studio apartment where the heat never quite reaches the city code minimum, trying to figure out where you went wrong.

In its worst form, depression seems insurmountable, a tsunami taunting you moments before it crashes down. Every time you resurface and get a breath in, you feel silly and regret everything you said, all the time wasted, all the people you pushed away. But when you’re trying to outrun the flood, it doesn’t help to know that the wave is actually only three feet tall. You’re still drowning. And you feel like the first person ever to do so.

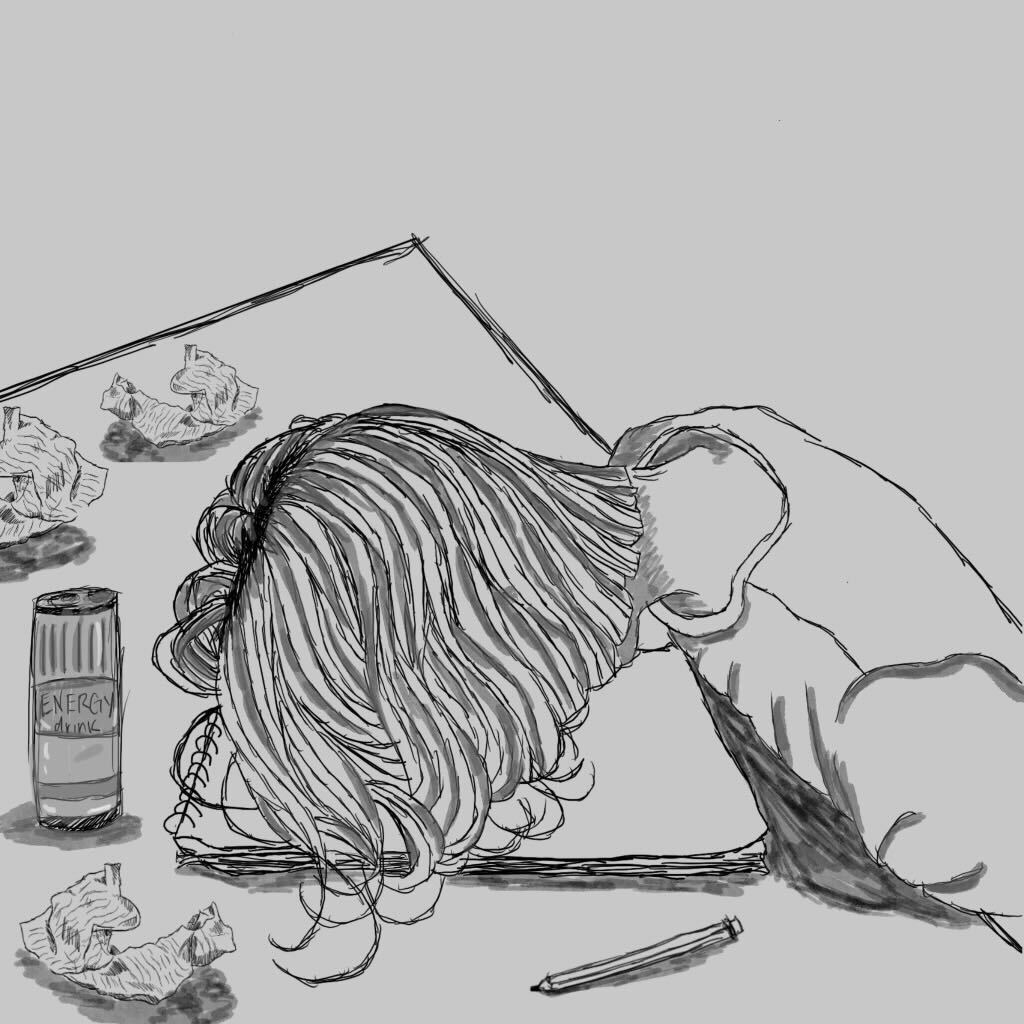

I’ve felt so much anger at myself for not writing. I’d tell people in a self-deprecating tone how absurd it was that I was a writing major who started crying every time they tried to start a paper, attempting to spin my frustration into something funny. I genuinely believed something in my brain had broken and made me a fundamentally uncreative person.

A depressed mind tears apart your writing before you even start, injecting loathing into the arteries that flow to your fingertips, scoffing at every word that could be more elegant, dragging you to the overflowing Wix portfolios of people you don’t know to show you how pointless it is to even try.

It convinces you that creative writing is a magical ability some people possess and others don’t. It makes you self-absorbed enough to believe everyone is waiting with steepled hands for the moment you finally let slip how mediocre a writer you are. It doesn’t want you to finish something and be proud of it, it wants you to prove it right. To protect yourself, you don’t write at all.

I even felt angry that I couldn’t exploit my feelings to use as writing material. I was envious of writers who wrangled their mental anguish into beauty and meaning and perplexed at how they did it. Why could Virginia Woolf and Albert Camus channel their angst into thought-provoking classics and I can hardly write a discussion post? Admittedly, they didn’t have millions of strangers with cameras and two cents salaciously vying for their attention inches away. But in the throes of “Woe is me,” not being able to make art out of pain feels like yet another personal failure, more proof that I don’t have the gene.

None of it is true. There is nothing but you and the finite number of words you know and the college newspaper that might print what you say. There is nobody waiting to jeer at your word choice or hackneyed topic or conversational tone. Shiv Roy, by god, you were right — “There’s just people in rooms trying to be happy.”

I wish I had an answer to the pain of mental illness, a real one with steps — for anyone who’s been through the same, but also for myself. You and I both know how empty advice and cheery encouragement ring when you’re low enough, and I won’t disrespect you by pretending to have something profound and transformative to say.

But you do have to hold out for change. That’s the one platitude I’ll hold us to, partly because it’s true, but also because it doesn’t try to gaslight you out of feeling pain in the moment. It’s something you can cling to at your darkest without cognitive dissonance.

As for the creativity block, minimizing self-hatred might have to happen before you can feel secure enough to try again. Fill pages with lists of your good attributes, things that you value or foods that you’d like to eat. Make collages of sweet texts people have sent you and photos from times you felt real pride. Do anything you can to untangle your self-worth from your ability to produce.

Practice distress tolerance by reminding yourself, no matter how awful you feel right then, that you had the capacity to love something before and that you will love something once more. Trust that your brain, that frustrating, enigmatic, spongy monstrosity, is not broken, and it will serve you again. Those neural pathways are still there. An audience for your creations can’t wait to see what you make next. The joy you used to feel will return, in small moments and big. Now that I’ve experienced it for long enough to write this column, I know it’s possible.

Doing the simplest, messiest, most mediocre version of whatever you used to enjoy keeps creativity in your life in the meantime. It’s easier said than done when you feel like you can’t do anything, but I’m talking toddler-level simplifications — doodle silly little creatures, hum along to familiar songs, knit one ridiculously long scarf in garter stitch. I don’t know if I can be a writer right now. But I can write some weird journal entries.

Livia Daggett is finally branching out from copy editing other people’s work to write her own. If you’re so inclined, write to her at LED88@pitt.edu.