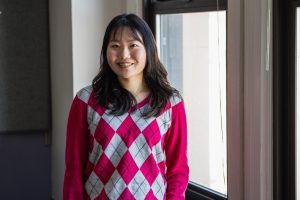

“My name is Janna. Like Janna Banana,” I announced, fidgeting nervously, to my classmates on the first day of fifth grade in suburban Alabama. I braced myself for impact. Maybe today, I could get past the introductions unscathed. Unfortunately, the onslaught of questions did not spare me from the cruel spotlight.

“Where are you from?”

“I was born in Washington State.” How else was I supposed to answer?

“No, like where are you actually from?”

“I’ve been living in America since I was born,” I responded, not even bothering to be subtle about my annoyance anymore.

“Okay, then where are your parents from?”

“They’re from Korea.”

“Oh, so you’re Korean! I thought you were Chinese. Is it true y’all eat dogs?”

I was stunned by the attack. This sort of response was not new to me, but every time, it still left me defenseless and dejected. As I looked down, I decided to let it go, convincing myself that it could have been worse anyway.

***

I walked into the bright classroom at my new international school in Korea, uncertain of what to expect. As I looked around at the sea of faces, I felt an odd sense of relief wash over me as I observed the majority of the students had features similar to me — black hair and brown eyes. For the first time in a long time, I was not nervous to introduce myself.

“Hello everyone, my name is Janna.”

“Hey Janna,” one of the students yelled, rather condescendingly, “what’s your Korean name?”

I hesitated for a second, considering the implications of the question for a moment. My Korean name was just something that was so foreign to me, even though it belonged to me.

“Um, I have one but I prefer to go by Janna.”

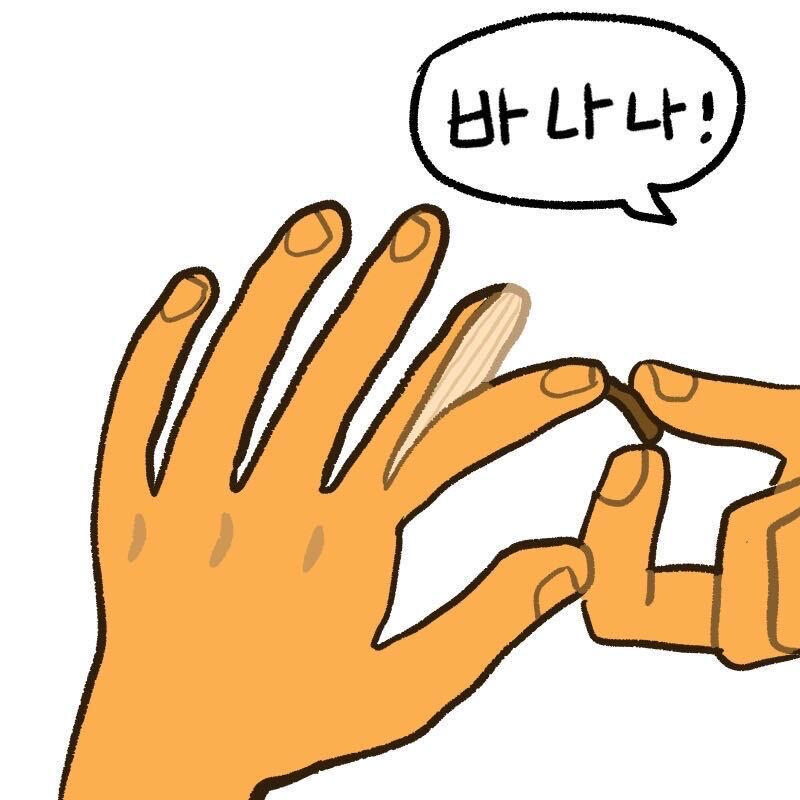

“Oh, well here, we mostly go by our Korean names (written in English). You’re a banana, aren’t you?”

“What do you mean?” I stammered. I had always taken pride in my American name, as I was spared from the frustration of having to correct other people from butchering it during roll call.

“Like a gyopo. Oh, I bet you don’t even know what that means.” They laughed.

I had no idea how to reply, so I forced myself to laugh along as I found an empty seat. A quick Google search later told me that a gyopo was used to define an ethnic Korean born in another country; yellow on the outside, white on the inside, like a banana.

***

“You’re not a true American.”

I could speak the language with no accent. I had an American name and celebrated American holidays. I watched the same television shows as the other kids to maintain social relevance. I threw away my smelly lunch that my mother packed for me. I’d constantly pinch my nose upward and roll my eyes — up, left, down, right — because I thought it would make my nose slimmer and my eyes bigger. I rebuffed any attempt to learn about my other culture. But it was never enough. Every year, when it was time to introduce myself to the class all over again, it was as if all efforts to whitewash myself quite literally washed off.

“You’re not a true Korean.”

The subtle jabs and reminders that were thrown at me, from scrutiny for speaking English in public to being spoken to like a toddler, or worse, being laughed at for my Korean, bothered me. It was starting to become embarrassing to realize how out of touch with the culture I had become. I soon started to do my makeup to fit traditional Korean beauty standards, watched countless K-dramas to improve my Korean, and danced along to K-pop music videos with friends to lyrics that I could barely understand at the time.

Growing up in rural Alabama, it was hard to contextualize the general ignorance and racism I encountered. Stuck at the convergence of two cultures that I was unsure of which to properly claim, it was only when I learned to value my own self-acceptance and the unique identity I possessed as a Korean American that I was able to stop being constrained to the boxes that people forced onto me — a way that provided them an easier narrative to digest and define me. Slowly but surely, I am stitching together my fragmented identities because I cannot be just American or Korean; I am both and I could not exist without either end of the yarn of my identity.