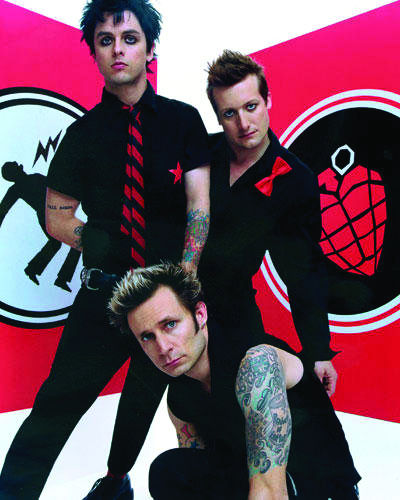

Time Capsule: ‘American Idiot’ captured the zeitgeist like no other, catapulted Green Day to arena status

September 29, 2014

“I don’t want to be an American idiot.”

This phrase is probably still uttered 10 years later under disenchanted breaths when citizens discover that the government spies on them and that the United States launched airstrikes at ISIS.

Green Day’s anthemic 2004 album American Idiot channeled bleeding-heart anarchy, capitalist oppression and Iraq War dissatisfaction into a record that metamorphosed the band from basement-dwelling Oakland, Calif. punks into a global rock band phenomenon.

Vulgar, brash, secular, heavy and hard-rocking, American Idiot made a strong political statement in rock opera form. In the vein of The Who’s Tommy, American Idiot took Green Day’s previously grungy and later poppy punk and solidified it into a massively crescendoing record detailing the story of “Jesus of Suburbia.” Even though it was its first-time foray into concept album writing, Green Day dropped an atomic bomb on the American public.

I consciously remember longtime Green Day fans’ reactions. They hated it. They denounced it. They said Green Day sold out because “American Idiot” charted at No. 1 in more than 10 countries. Moms who never knew or cared about the pot-smoking misfits before “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” belted the words to “Wake Me Up When September Ends” on the pop radio stations. It was seminal. It was radioactive. It was utterly inescapable in that year.

It begins with a punch in the face on the track “American Idiot.” Billie Joe Armstrong patronizes, “Don’t wanna be an American idiot/ Don’t want a nation under the new media/ And can you hear the sound of hysteria?” setting the tone for what follows is not typical Green Day schmoozing — it’s a calculated, organized and belligerent assault on the state of affairs both lyrically and instrumentally.

What follows from this initial outburst is the nine-minute long, five-movement anthem “Jesus of Suburbia,” which rewrites the band’s entire musical repertoire. It could easily be culled from The Who, the Rolling Stones and “West Side Story” as a highly experimental mix, establishing it as one of the most compelling songs on the album because of its unexpected novelty. Sonically, its meridian movements “City of the Damned,” “I Don’t Care” and “Dearly Beloved” depart so far from Green Day canon that the teenaged suburban angst turned off the band’s early followers and inspired a brand new breed instead.

A similar deluge, “Homecoming,” serves as the climax of the album with another five-piece momentous structure. It emphasizes the phrase, “We’re coming home again,” amidst booming timpani and military-precision snare drums — a chilling proclamation, especially when compared to the actual homecoming of soldiers, as the last ones in Iraq did not return until 2011. The denouement — the anticlimactic but resolute “Whatsername” — maps out the wonder of lost connections, in a perfectly somber and sincere tone contrary to the riotous intro.

American Idiot stands not only as a hugely influential rock album but also as a cultural artifact. The response was nationwide: Depressed youths clung to the figure of Jesus of Suburbia, musicians started copying Green Day’s sound and look and people realized it was okay to criticize the Bush administration, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and propagandist media. The explosion resonated in the societal sphere. For months, it was the only CD in the Discman.

American Idiot toured the world extensively, leading to a live album called Bullet in a Bible. The tour played straight through the first half of American Idiot before branching out to some older hits from Dookie (1994), Insomniac (1995) and Nimrod (1997), signaling the band’s dependence on the American Idiot brand and the fans’ willingness to consume it. The record turned them from a moderately successful club band into arena superstars.

In 2009, Green Day wrote the follow-up to American Idiot titled 21st Century Breakdown. It tried, very hard, to be American Idiot Pt. II, but it lacked the anti-political, anti-war, post-industrial fervor that rocked the U.S. in 2004, and coupled with mediocre songwriting, the album disappointed thematically and aurally, despite profound sales figures.

Most importantly, 21st Century Breakdown’s epic grandiosity lent itself to the kind of songwriting Armstrong wanted in the musical adaptation of American Idiot. Numerous tracks, including “21 Guns” and “Know Your Enemy,” amended the soundtrack for the Tony-winning Broadway version that staged five years after the album’s initial release.

Absolutely brilliant onstage, the “American Idiot” musical added the bodies necessary to facilitate a kinetic and anarchic punk-rock opera. Just like the hazy acid trips in “Tommy,” “American Idiot” offers whirlwind sights, gags and color under the guise of narcotics.

After the success of American Idiot, Green Day’s trajectory changed forever and not in a promising way. In its feverish denouncement of capitalism, the members of Green Day have arguably become some of the best-selling artists in the country, fettering their integrity for the sake of politicizing. It might be a “phase,” but the music matures along with its writers — a little less “Walking Contradiction,” a little more “Good Riddance.”

There aren’t too many future “classic rock” bands I can foresee, but Green Day tops that list. Green Day will probably never recreate American Idiot’s successes without the same historical context. The album marked a decisive change for the band, so it’s only a matter of time to see what comes next for Green Day, the government, the economy and the world.

Sometimes, everything isn’t meant to be OK.