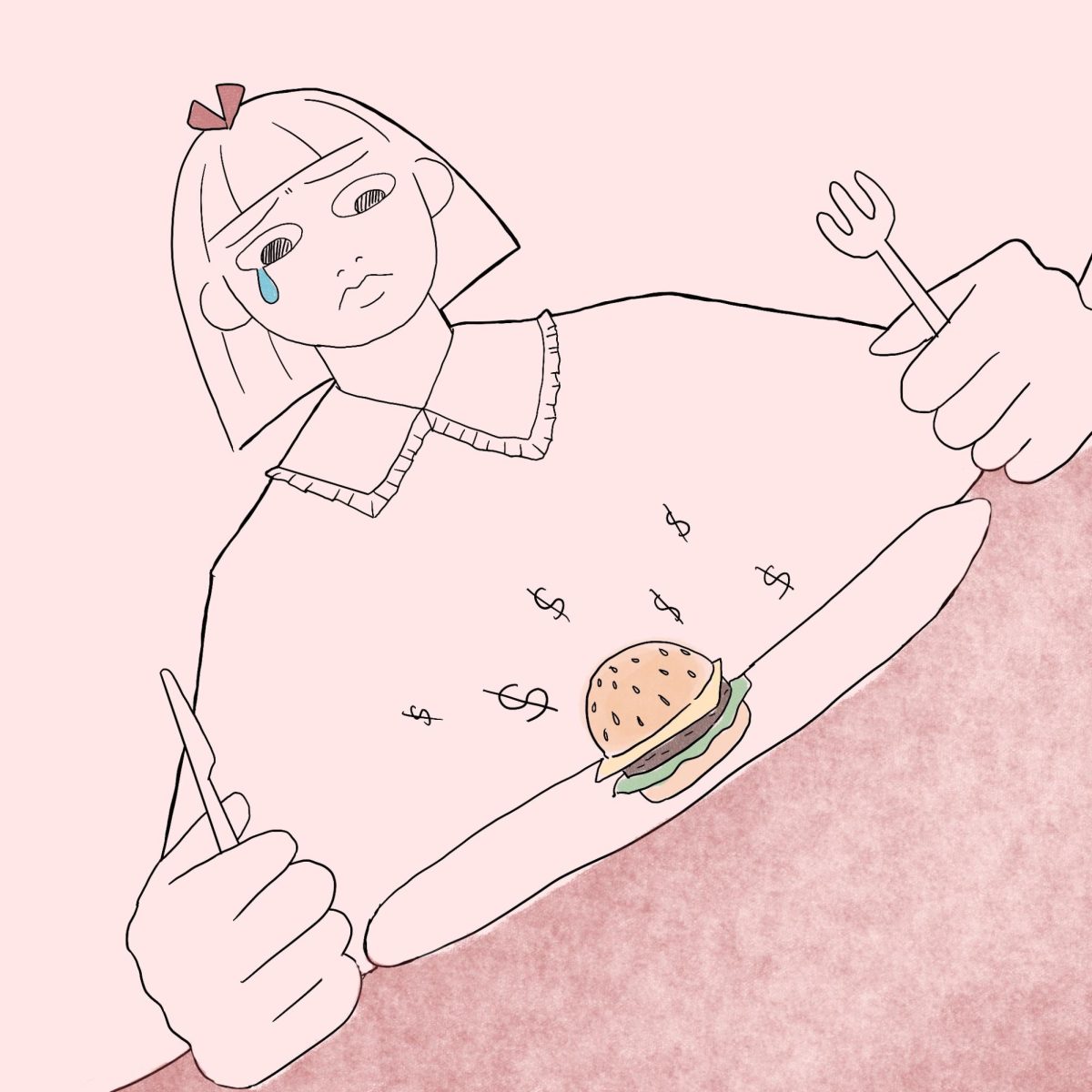

Wasting away in Margaritaville: Get real about the economy

September 12, 2014

It feels that, often, this country’s understanding of the economy is like an episode of “South Park.”

Specifically, it’s like the one in which Randy Marsh convinces the entire eponymous town to spend money on nothing but “the bare essentials. Water and bread and margaritas,” to appease the economy and bring prosperity back.

Sadly, as evidenced by the past five years of recession, things are a bit more complicated than that. GDP is increasing, and the stock market is reaching new heights. But these numbers don’t indicate much for the everyday person on the street. All we see is the unemployment rate, which is still more than 6 percent — high for the “prosperous” times indicated by more abstracted measures.

The one thing “South Park” got right in its analysis of the recessionary mindset is the search for a scapegoat. When a slowdown occurs — or continues to occur, for that matter — people need to throw blame at somebody’s feet — especially in an age of 24-hour media coverage. So, who shall we ready the pitchforks for? The president of course!

Yes, it is a tradition that goes back to 1876 to blame the sitting president — and his ruling party — for an ailing economy. In that year’s election, the Panic of 1873 — “panic” being old-timey English for depression — had led to 7 percent unemployment. The ruling Republican Party’s candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, almost lost the election to the party of the Confederates and secession, the Democrats, a mere decade after the end of the Civil War.

Then there was Herbert Hoover, who was thrown out of office in favor of Franklin D. Roosevelt because of the Great Depression and a 20 percent unemployment rate. And even Ronald Reagan, though known now as some sort of conservative superman, had his disapproval rating touch 50 percent in the early ‘80s as the economy slowly recovered.

Thus, the general rule, as backed by a 2010 Pew study, is that if unemployment is going up, presidential disapproval will, too.

But this is unfair to any president, even Herbert Hoover. No president can single-handedly change the economy in a constitutional manner. It requires, at first, agreeable lawmakers from both the local and the federal level, not to mention a willing public.

These are incredibly difficult conditions to meet. Yet it was able to happen once in our history with FDR. In 1933, after his election, he was able to pass bill after bill to try and fix the economy, because he had the right conditions — lawmakers and a public willing to do anything to get out of the depression. And it worked, at least, to an extent.

While economists can argue for days about the exact cause, GDP rose, and unemployment fell following FDR’s election. That said, the Supreme Court eventually stepped in and found the main New Deal program, the National Recovery Administration, unconstitutional. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve — also not under FDR’s control — raised interest rates, thus increasing the price of much-needed private investment. In 1937, the economy plunged again.

What the history of the relationship between the presidential approval rating and employment shows are the issues that led Winston Churchill to utter his often-quoted expression, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.”

We, as Americans, whether liberal or conservative, want our government to be ready to react to every recession, passing the exact laws needed to get everyone their job back with a 15 percent raise. But to fight a recession in such a manner, the government would need to be acting under a unified plan that takes no regard for precedent or for even the good of the people, except as a whole — like FDR’s New Deal.

The price of living in a country with freedom is that nothing can be done overnight, and nothing can be attained without sacrifice. Compromise is the lifeblood of the democratic process. Unfortunately, our current Congress seems to enjoy treating every issue as if it were a life and death struggle over the very ideals of the republic and that any step back would certainly end in the destruction of America.

This is unhealthy for our national mindset and unhealthy for the economy.

Take the government shutdown in 2013, for instance. Inaction on key issues, such as healthcare, inhibits business owners from planning accordingly for the future. This means no investment, no expansion and no consistent sources of new jobs.

Stable government policies encourage economic growth — realistically, this doesn’t mean rigid policies. Congress will have to adjust taxes periodically and tweak regulations. Passing and implementing policies, such as healthcare, is stable while threatening to make the government shut down over policy change is not.

Yet, stability for the economy should not be seen by the public as a constant straight line. Things like tax rates can fluctuate from 0 to 40 percent and people, acting as both consumers and producers, will know how to take these changes into account for their business or their budget.

There will always be imperfections in the regulations (or lack thereof), but legislators must change them later on. The government does not have to get the economy right the first time. The economy can help itself.