Protestors sit down, urge Pitt to stand up for justice

April 9, 2014

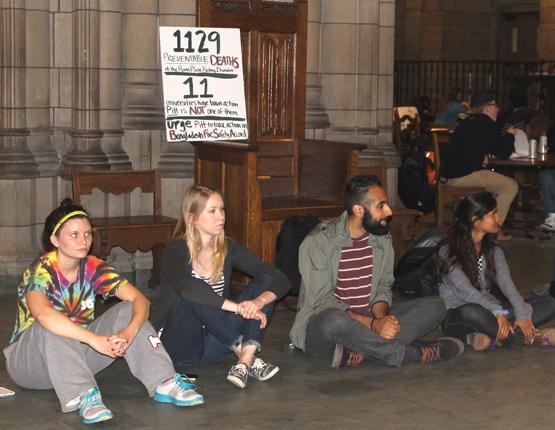

Students attempting to stage a “die-in” yesterday to draw attention to recent advocacy efforts were forced back to life by University administrators and campus police.

About 25 Pitt students, including members from two student groups focused on social justice, participated in a passive protest by attempting to lie down in the Cathedral Commons to simulate dead bodies.

The students intended to protest the University’s lack of response to calls to sign the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, an independent and legally binding agreement that holds corporations accountable for workers in their factories in Bangladesh.

The groups included Americans for Informed Democracy, an advocacy group at Pitt, and members of No Sweat: Pitt Coalition Against Sweatshops, a student group affiliated with AID.

According to Joe Thomas, cofounder of AID, the simulation symbolized lives lost to poor factory safety.

The Accord was developed last summer after the collapse of Rana Plaza, a Bangladeshi garment factory, causing the death of 1,129 factory workers.

“This is how students have to communicate with administrators,” Thomas, a senior biology and political science major, said.

But before the students could lie down, campus police, Vice Chancellor for External Relations G. Reynolds Clark and Kenyon Bonner, director of student life and associate dean of students, delayed the protest by 15 minutes.

Instead of allowing the students to lie down in protest, University officials let them stage a sit-down protest. For about 20 minutes, demonstrators sat on the floor of the Cathedral of Learning common room in two lines.

According to University spokesperson John Fedele, the demonstrators were not allowed to lie down because it would be considered a tripping hazard.

The students would have had to reserve the Cathedral Commons for their event in order to lie down, Fedele said.

Julie Radomski, AID’s vice president, said the goal of the “die-in” was to get the University to sign the accord.

“We want to prove this is something that Pitt students really care about,” Radomski, a senior anthropology and economics major, said.

AID organized the protest after feeling unheard in their efforts to lobby the University into signing the accord, Radomski and Thomas said. The organization has submitted letters and a petition with hundreds of signatures to Chancellor Mark Nordenberg urging the University to sign the accord.

To further progress on signing the accord, Radomski and other members of AID have been meeting with Lori Burens, coordinator of licensing in Pitt’s Athletics Department. However, the decision to officially align with the accord lies in the hands of University officials, Radomski said.

Following Burens’ suggestion to approach the chancellor about aligning with the accord, Radomski met with Nordenberg “informally and briefly” at a reception and dinner for the Bellet Teaching Award about two weeks ago. Radomski said she felt that Nordenberg did not think the issue was relevant to Pitt.

Fedele said Pitt officials are currently considering the matter of signing the accord and are in the process of reviewing the accord with the Collegiate Licensing Company, which coordinates licensing agreements between suppliers and Pitt.

“Students will be notified when a decision has been made,” Fedele said in an email.

At 12:45 p.m., after discussing the matter with campus police, Clark and Bonner, about 25 students were finally allowed to sit in the Cathedral Commons for their protest.

The 15-minute discussion between AID, the police and administrators received more attention than the actual protest. A small crowd of about 10 protesters gathered in front of the main entrance to the Cathedral to talk to the administrators, obscuring the doorway.

During the 20-minute protest, Nick Goodfellow, a junior and AID board member studying communications and rhetoric, passed out fliers asking passersby to sign the group’s petition.

Goodfellow said he finds it concerning that Pitt has waited this long to start talking about this issue.

“I think we got a response from the administration,” Goodfellow said after the protest. “My Pitt apparel shouldn’t come at the expense of workers’ lives.”

The accord aims to encourage stricter regulations and safety procedures to prevent a collapse like the one at Rana Plaza from occurring again by committing retailers to be more diligent about safety and fair pay.

The Worker Rights Consortium, an independent organization monitoring labor rights around the world, issued a recommendation to all aligned universities to sign the Bangladesh Accord in September 2013. Pitt aligned with the consortium in August 2013 but has yet to sign the accord.

The accord is an independent agreement that requires all garment factories in Bangladesh to have safe work environments by holding retailers responsible for safety issues and workers’ wages. By signing the accord, Pitt would require the licensees of its apparel to be held accountable for the conditions of their workplaces in Bangladesh.

Currently, 11 Pennsylvania universities have already signed the accord, including Temple, Penn State and the University of Pennsylvania.

Clark said that there is a long process before the University can decide whether to sign the accord or not. Clark said the University has shown that it takes students’ considerations on this matter seriously by first aligning itself with the Worker Rights Consortium.

“We weren’t dragging our feet,” Clark said. “Our decision will be based on what’s in the best interest of the University of Pittsburgh.”

Liza Boulet, a senior environmental studies major, also participated in the protest.

“I think it’s not good we haven’t signed an agreement yet to make it official,” Boulet said.

Mohammad Mozumder, a doctoral student teaching an undergraduate course on social change, lived in the Mirpur area of Dhaka in Bangladesh, near the shanties where garment workers stayed.

He said that the shanties usually lack electricity, gas and access to safe water, and there can be four to five people renting a tiny space to save money.

“[Garment workers] often cannot even afford the necessary food to keep them healthy,” Mozumder said in an email. “I think the accord is an important one, because it legally binds the stakeholders to take responsibilities.”

Mozumder said that many poor and unemployed people are ready to work for whatever wage their prospective employers offer and in whatever working conditions are available.

“The Western companies and local suppliers capitalize on the vulnerability of those poor people,” he said.

Editor’s Note: In an article published on Thursday, April 10 titled, ‘Protestors sit down, urge Pitt to stand up for justice,’ The Pitt News reported that Pitt spokesperson John Fedele said, “ … the demonstrators were not allowed to lie down because the commons is a reservable space, and it would be considered a tripping hazard.” Fedele never said that the Cathedral Commons is a reservable space. The Pitt News regrets this error.