When John J. Audubon, the famous wildlife artist, came to Pittsburgh nearly 200 years ago, he paid specific attention to the passenger pigeon.

Audubon, however, was more concerned in 1817 with the aesthetically pleasing aspects of the brown, blue and red, sleek birds than the scientific accuracies of their feeding patterns.

“He did it pretty wrong in that painting. It’s a beautiful painting, I actually have a print of in my house. But in that, he shows the female feeding a male and the male is in a begging position,” Chris Kubiak, the director of education at The Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania, said. “We now know that is false. It would’ve been the female begging, it’s a sort of mating ritual.”

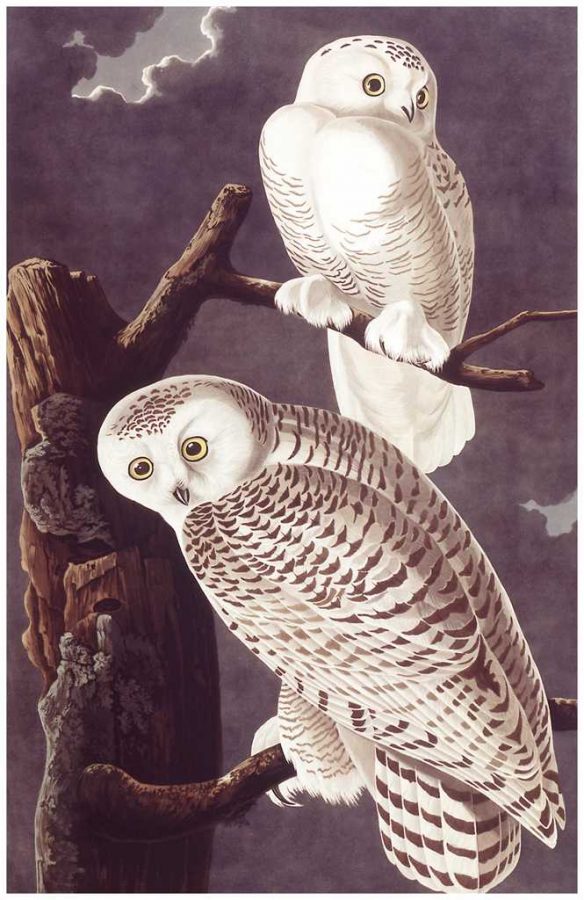

Audubon’s work — noted not for his scientific renderings, but rather his artistic ones — will be on display in Hillman Library on Friday, Nov. 6, in honor of the fifth annual Audubon Day. In the late 1800s, George Bird Grinnell named the National Audubon Society after the artist because of his contributions to the study of birds and their habitats. The University initially created Audubon Day in 2011 and other later institutions followed suit in celebrating the artist who focused on wildlife in the United States.

The University is one of a few institutions — including the Carnegie Library — in the world to own a complete set of Audubon’s “Birds of America” prints. “Birds of America” is one of the largest records of bird species found in the United States during the early nineteenth century.

Anthony Bledsoe, a lecturer on ornithology at Pitt, said Audubon’s style of presenting the birds was ahead of his time.

“Audubon used what we like to call today as the barrel-of-the-shotgun method,” Bledsoe said. “After he killed the birds, he would use a complex system of wires and strings to position the birds. Previous artists would draw the birds in a stiff position, but Audubon was different. He drew the birds in dynamic ways, by positioning them how he would observe them in the field.”

Birders, historians and artists revere the prints for their hand-painted and printed artistic finesse.

Jon Darlington was an attorney from Pittsburgh in the late 1880s who had a keen interest in American history. His vast collection of maps, lithographs and works of art included the entire set of Audubon’s “Birds of America,” prints that date back between 1827 and 1839.

The Darlington family donated the prints as part of The Darlington Memorial Library in 1918 and 1925.

Eighty years later, the Darlington Digital Library — a digital collection of Pitt’s special collection that includes the earliest books, manuscripts and maps in Western Pennsylvania — displays a series of 25 prints from Audubon’s “Birds of America” collection once a year. The collection includes 435 original prints. Pitt has one of the 120 complete sets that exist today in its Darlington Memorial Library.

The Audubon celebration at Pitt on Nov. 6 will feature guest speaker Allan Stypeck, owner of Second Story Books in Washington, D.C., and an appraiser of Pitt’s Darlington Library Collection at 10 a.m. in room G-47 of Hillman Library.

According to Stypeck, most first edition collections of Audubon’s “Birds of America” separated over time and are now sold as singular prints. Full collections like Pitt’s are rarely for sale on the artistic market.

Stypeck said a “fair insurance value” for a collection in good condition would be around $11 million for replacement value.

“If the items are very difficult to obtain, like the subscription issues and the first complete folio editions of the ‘Birds of America,’” Stypeck said, “the value will increase based on the market interest.”

Jeanann Croft Haas, the head of the special collections department at Pitt, described the long process Audubon undertook to complete each print.

“When Audubon set out to do this in the nineteenth century it was such a huge endeavor,” Croft Haas said. “He basically hunted the birds, posed them, painted them and then he had to hire an engraver and a team of colorists to then color the engravings.”

After immigrating to the United States from France in 1803, Audubon dedicated his life’s work to observing and cataloguing natural life in the United States. He spent the next 20 years traveling the country, documenting and capturing the birds of the nation.

Kubiak, the guest speaker at last year’s Audubon Day in the Amy E. Knapp room in the Hillman Library on Nov. 21, remarked that Audubon would not necessarily be considered an ornithologist — someone who studies birds — by today’s standards.

“One of the things he gets criticized for is that he really wasn’t a scientist. He was an artist first and foremost,” Kubiak said. “Back then he would have been considered, for lack of a better term, they were called ‘gentleman scientists.’ Again, someone who didn’t really have formal scientific training.”

Audubon’s depictions of birds in the early twentieth century are one of the only visual records ornithologists have today of the bird species that inhabited the United States during that time.

For Haas, Audubon’s work can not be confined as either artistic or educational because it encompasses both.

“It’s significant from an artist’s perspective, and it’s significant from an ornithologist’s perspective,” Haas said. “I think it’s one of those works that transcends boundaries. It’s an interest to almost everyone for a different reason.”

Editor’s note: Because of an editing error, an earlier version of this story referred to John James Audubon working in 1917. Audubon was working in 1817. An earlier version of this story also said the Darlington Digital library was started eight years after the family donated Audubon’s prints. The Digital library was started 80 years after the family donated the prints. The story has been updated to reflect these changes.