What it means to be a human doesn’t warrant a black-and-white response.

Monday’s “Poetry and Race: How the Humanities Engage with Social Problems” will highlight this theme by examining how African-American poetry engages with contemporary social issues, like police violence.

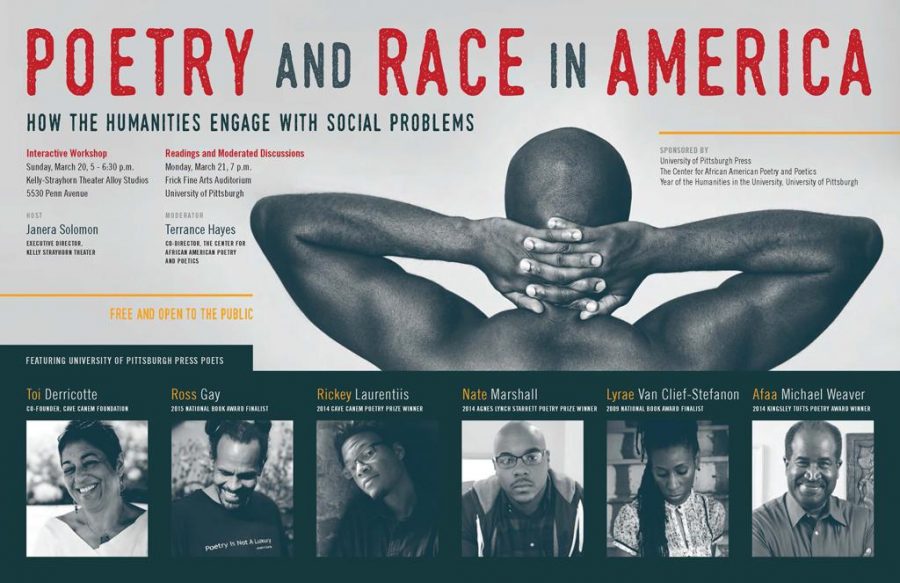

As part of Pitt’s “Year of the Humanities” theme, the Frick Fine Arts Auditorium will hold readings at 7 p.m. by six poets published in the University of Pittsburgh Press. A discussion on the humanities’ role in race and society will follow.

For Terrance Hayes, the event couldn’t come at a more pertinent time.

“[African-American poetry] does change. We’re in a different moment,” the event’s moderator and acclaimed Pitt English professor and poet said. “The conversations are deeper, and nuanced, and maybe surprising to people who haven’t thought about it very much.”

The discussion comes at a critical time in our nation’s recent history. In the event’s release Hayes cited instances of “systematic police violence against African Americans” in New York, Baltimore and Ferguson, Missouri, that make “Poetry and Race” a timely necessity.

In addition to serving as a platform for African-American art, the event is also the first endeavor for Pitt’s new Center for African-American Poetry and Poetics, which will officially open in the fall. The center, where Hayes and associate professor Dawn Lundy Martin will serve as founding directors, aims to be a “creative think tank” for African-American poetics as well as an artistic incubator for writers, scholars and other artists, according to its website.

Poets Toi Derricotte, Ross Gay, Rickey Laurentiis, Nate Marshall, Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon and Afaa Michael Weaver — all of whom the University of Pittsburgh Press has published — will read excerpts from their individual works.

“We wanted to highlight the great work of the press, the work that the poets have been doing, and to bring that to the city and to the students,” Hayes said.

The idea for “Poetry and Race” has been in the works since the fall, following Provost Patricia E. Beeson’s April declaration that the 2015-2016 school year would be the Year of the Humanities. Hayes worked in collaboration with Peter Kracht and Ed Ochester, the University of Pittsburgh Press’s director and editor, respectively, to organize “Poetry and Race.”

In line with the CAAPP’s and the Year of the Humanities’s mission, “Poetry and Race” is about rethinking how society treats the humanities, particularly in regard to social interactions.

“Listening to how [the poets] express themselves through the poetry might increase [students’] awareness of how the arts are connected to all of us and to social issues, and to the humanities,” Maria Sticco, the University of Pittsburgh Press’ publicist, said. “These poets are offering a real insight into the issues of race and how we can all better understand each other.”

In order to capture a holistic portrait of African-American poetry’s social commentary, Hayes, Kracht and Ochester chose poets from across three generations.

“We had a lot to choose from, and we thought that would be an interesting way to build it,” Hayes said, emphasizing their variety’s value.

Not only do the poets’ generations set them apart, but so do their native regions — which include Chicago, New Orleans, Indiana, New England and Pittsburgh — and the styles in which they write.

“Even though they’re six poets of African-American descent, their other identity claims are different,” Martin said.

Derricotte, Weaver and Gay are all recipients of the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, one of the most prestigious awards for contemporary poetry, which comes with a $100,000 grant.

As an art form, Martin said poetry specifically has a distinctly different effect on listeners and society than visual art.

“Poetry often happens in public space. It’s an aural form, often, so it has the power to affect in a different way than say, looking at a work of art on a gallery wall,” Martin said. “It has the opportunity and power to reach a broad base of people.”

Echoing the Year of Humanities’s initiative, Hayes emphasized language’s role in helping us better understand the humanities, and each other.

“Poetry’s major engine is language, so, of course, social change doesn’t really happen without the effect of communication,” he said. “Language is the key to everything. It’s at the root of the humanities.”

Martin also noted how current events have shaped the way she writes her poetry.

“Increasingly, my own poetry looks more directly at racial injustice in this country, because it’s more at the forefront of our lives,” she said. “We’re at a particular historical moment where things are really changing, and racial strife has kind of re-risen to the surface of our culture.”

According to Martin, there is no one particular point to “Poetry and Race’s” readings. Despite its African-American poetics, the event is more a celebration of the six poets’ accomplishments than a “themed seminar.”

“Although they’re African-American, or of African-American descent, they might all approach the issue of race and social change, and race and what it means to be human, in very different ways,” Martin said.

Hayes anticipates that some people may expect the event to be a cliched conversation, one that’s been done before. He wants to make sure that “Poetry and Race” exceeds those preconceptions.

“My challenge as a moderator is to not have it confirming what everybody believes it’ll be,” he said. “I want to surprise people and deepen their sense of what it means to be looking at these poets in this contemporary … to make that a little deeper than what people’s preconceived notions are.”

“Poetry and Race’s” theme and efforts may seem inspired by recent unsettling violence, but the reality is actually more uplifting.

“This conversation really contributes significantly to this question of what it means to be human,” Martin said.