A little sweat and exercise can preserve brain tissue and help prevent Alzheimer’s disease, according to a new Pitt study.

UPMC and the University of California, Los Angeles, co-published research last week in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease that claimed exercise can protect against cognitive decline over a five-year period. Delaying dementia onset by five years could cut the prevalence of the disease by nearly half, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

This is the first study to take all forms of exercise into account rather than prescribed forms, such as the number of blocks walked. The authors converted all of these different activities, including swimming, running and playing various sports like tennis, into a common unit — calories — which they then related to cognitive decline and changes in the size of different brain regions.

The National Institutes of Health estimates that 5.3 million Americans currently have Alzheimer’s disease, and by 2050, the NIH expects that number to nearly triple as the median age increases. There is currently no treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.

The study consisted of 876 participants over the age of 65 drawn from a previous large scale, multi-site study conducted in the 1990s that initially assessed cardiovascular health in seniors. These authors repurposed the data to ask how exercise impacts brain structure and cognitive decline.

From 1998 to 1999, subjects of the earlier study received a structural MRI brain scan and cognitive assessment and recorded time spent exercising. Five years later, 326 participants at the Pittsburgh site followed up with another cognitive assessment.

The researchers found that the more calories a person burned, the larger certain parts of their brains were. They also found a connection between calories burned, brain preservation and cognitive decline over the five-year study.

“The parts of the brain that are affected by exercise are also the ones that can protect you from subsequent decline,” said co-author James Becker, a professor of psychiatry, psychology and neurology at Pitt. “Exercise improves the brain. The brain is what holds off the dementia. And that is new.”

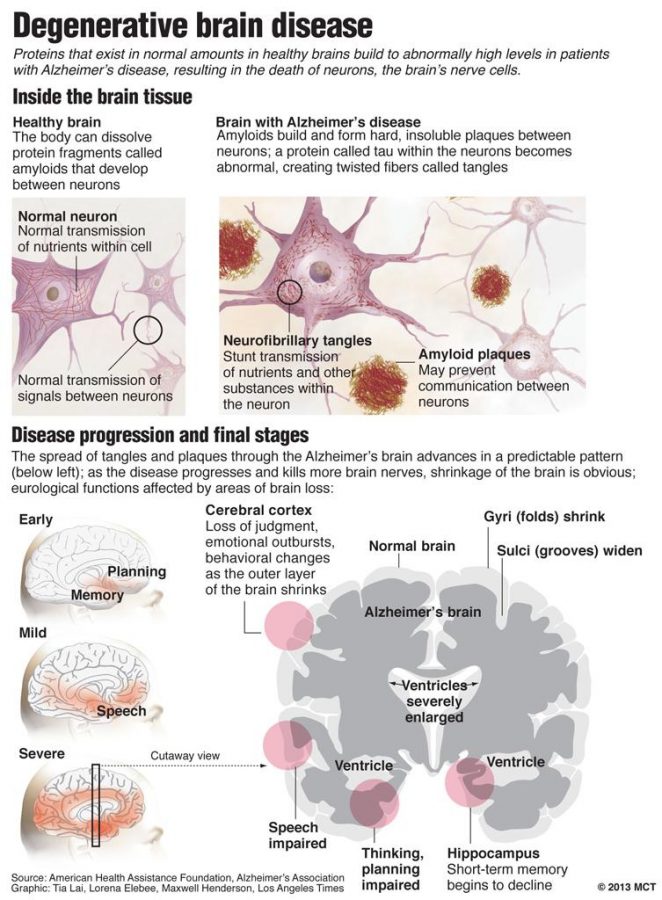

The researchers found that the hippocampus and precuneus were among the brain areas found to be larger in people who burn more calories than those who don’t exercise as much. Both areas help store memories and contain recall functions, which is the most obvious impairment of Alzheimer’s patients.

According to the study, burning calories, regardless of the type of exercise, may reduce the loss of neurons in structures of the brain central to memory, which delays the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Seniors see the connection between exercise and cognitive decline firsthand.

“The majority of my friends are [active], and the one or two who aren’t … I can really see the difference,” said Karen Miyares, age 74.

For some seniors, the threat of mental decline drives them to be active.

“I don’t want to get to that point. That’s why I keep moving,” said Florence Williams, age 79.

Miyares and Williams both attend weekly fitness classes at the Stephen Foster Community Center in Lawrenceville. Class offerings include line dancing, tai chi, yoga, aerobics and strengthening. Neither woman pays out of pocket for these classes, thanks to the SilverSneakers program from Medicare, which is an initiative aimed at encouraging seniors to be more active.

“I’ve been doing this for about 20 years, and I think I’ve come across only two or three [people] that ended up having Alzheimer’s,” said Nancy Klinvax, a fitness instructor at SFCC.

Klinvax said this research could motivate seniors to be more active.

“It’s very hard to get across to them … that it’s good to sweat,” Klinvax said.

And the sooner seniors start to sweat, the better, according to lead author Cyrus Raji, a resident in diagnostic radiology at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center.

“No study has shown that exercise can reverse cognitive decline if you already have Alzheimer’s, but the rate of decline is slowed,” Raji said.

Becker said primary care doctors should discuss lifestyle changes with their patients at midlife because it might be too late otherwise. According to Raji, some clinics, such as one at Cornell University, are already starting to use exercise as a way to prevent Alzheimer’s.

To co-author Kirk Erickson, professor of psychology at Pitt, exercise is a fitting prescription.

“I think [exercise] is one of the most promising interventions and treatments that we have right now,” Erickson said, “and one of the only ones available.”