Reconstructive technologies developed to aid veterans injured on the battlefield

October 24, 2013

Most people will never have to imagine what life is like without a face.

But for more than 16,000 military service members severely wounded in battle in Afghanistan and Iraq, coping with burns, amputations and injuries to the head and face are part of everyday life.

In 2008, the U.S. Department of Defense established the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine program and chose the University of Pittsburgh and UPMC, along with Wake Forest University, to receive $45 million to develop new technologies for healing the types of wounds that became common in Iraq and Afghanistan. This year, the department announced that it would spend a total of $75 million for the second phase of the project.

Rocky Tuan, the director of the Center for Military Medicine Research, a joint program of Pitt and UPMC, said there is a real need to research ways of repairing tissue.

“Because of excellent body armor now,” Tuan said, “most injuries are not lethal.”

He went on to say the survival rate for injured U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan has been greater than 90 percent.

“It’s very rare to get internal organ injuries,” he said. “Therefore, the injuries are in the extremities, the limbs and the head.”

Tuan is Pitt’s executive vice-chairman of orthopedic surgery, the associate director of the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine, and the director of the Center for Cellular and Molecular Engineering.

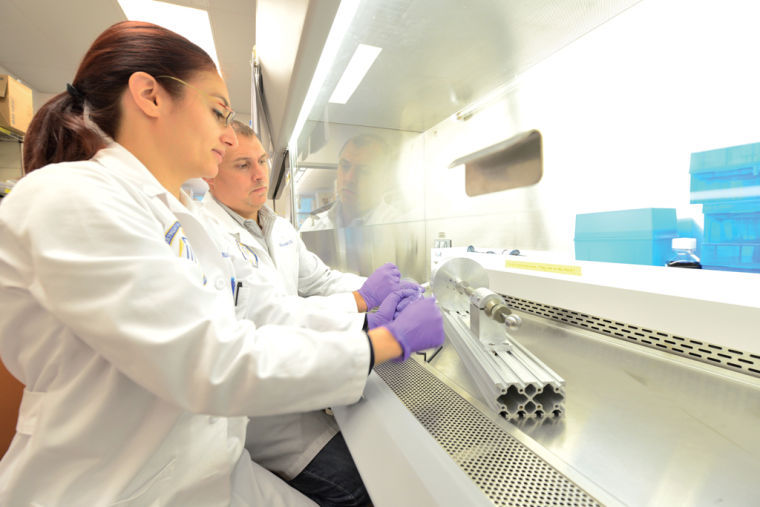

The Pittsburgh research team is focused on treating injuries in five different areas: treatment for craniofacial injuries, which affect the face and head; limb and digit salvage; burn treatment; scarless wound healing, and dealing with compartment syndrome, which occurs when pressure builds up from swelling or bleeding within a healed wound.

One new procedure the Pittsburgh team developed for treating burns involves a device that researchers refer to as a skin gun. The skin gun was developed by the Pittsburgh research team during the past four years, and is presently used in clinical trials.

“You put stem cells into a spray gun,” said Tuan. “The stem cells can be sprayed upon the wounded area or the burn area, and we can reconstruct the skin.”

These stem cells come from the bone marrow or fat tissue of the wounded person. Stem cell research is a big part of his team’s approach, not only in burn healing, but also in facial regeneration and in restoring function to injured joints.

Another new procedure that is presently going through clinical trials is a total hand transplant. It’s a difficult procedure not only because of the complex surgery but also because of the immune system’s tendency to reject a foreign limb. In addition, there is only a small window of time during which an organ donor’s limbs would be viable. According to Tuan, UPMC is the most advanced hand transplant institute in the U.S., having completed eight transplants.

Matthew Hannan is a U.S. Marine Corps veteran and the president of Pitt Vets, an on-campus support and mentoring network for student veterans. He is also a research assistant at Pitt’s Human Engineering Research Laboratories, where he works with wounded veterans.

Hannan said that maintaining independence and reintegrating with society are often two of the biggest challenges for injured veterans. These new regenerative therapies could help veterans to overcome those challenges.

Hannan could think of many examples of veterans who could benefit from new procedures.

For example, Hannan said that a veteran who receives a limb transplant might therefore not need to rely on a motorized wheelchair or a robotic arm to assist in handling objects. Or in the case of burn victims, a successful craniofacial procedure may make a veteran more comfortable going out in public and less likely to be sunburned when exposed to sunlight.

“My father is a Vietnam vet,” said Hannan, “and the big thing with veterans is we’re humble. We don’t want to admit we’re weak or sick or hurt, but we want to be independent.”

He said there was a serious risk with some of the new procedures. For example, a surgery that doesn’t go well could further isolate or demoralize a veteran. Hannan noted that these procedures are optional treatments that require patient consent before they can be conducted.

According to Ron Poropatich, the executive director of the Center for Military Medicine Research, research on regenerative medicine, while focused on helping veterans, will ultimately benefit all of society.

“Every problem we have in the military exists in the civilian sector, as well,” said Poropatich. “So the relevance doesn’t change, it’s just that the priority is greater.” Poropatich is a retired U.S. Army colonel who has worked for 30 years in military medicine research and acts as a facilitator for both military and Pitt researchers. He described a new technology called high-definition fiber tracking, which will help treat traumatic brain injuries.

High-definition fiber tracking takes MRI images and processes them through a complex algorithm. The data is uploaded to a portable device such as an iPad, allowing veterans with traumatic brain injuries to work with rehabilitators to see precisely what areas of the brain are damaged — a process that can lead to highly customized rehabilitation.

“[A traumatic brain injury] is like cancer,” said Poropatich. “There are different degrees and different levels, [but] you have to treat it in a very individualized way.”

He also said that high-definition fiber tracking would also have implications in treating Alzheimer’s and autism.

“The whole thing comes down to an academic-government partnership,” said Poropatich. “We have a lot of scientific experts at Pitt. By collaborating, we can come up with solutions a lot faster.”