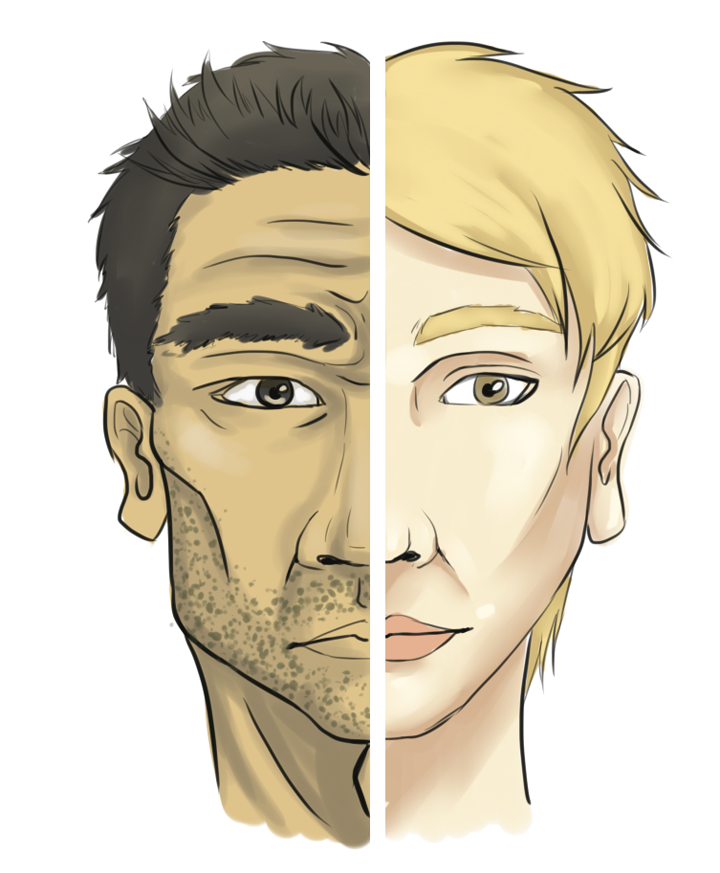

In September, Duke University’s Women’s Center began a nine-week program for men — called the Duke Men’s Project — to discuss masculinity, feminism and intersectionality. The program touches on several topics, including male privilege, sexuality, gender diversity, intersectional feminism and the language of dominance. While some see this as an attack on traditional masculinity, others see this as an opportunity to include men in conversations about women’s issues. Not sure what to think? Our columnists, Amber Montgomery and Jordan Drischler, give their takes on the project from opposing sides of the issue.

Amber Montgomery: Duke’s men’s program rightly includes men in the discussion

(Drischler’s argument begins at the end of this column)

Like many Pitt students, I spend a lot of time in Hillman Library scrolling through the internet in an effort to procrastinate actual work. One day, while getting lost in Reddit threads, I stumbled upon a frightful but exhilarating find: a thread called The Red Pill.

If you’re not familiar, The Red Pill is an online community for people to share their experiences in what they feel is a “culture lacking a positive identity for men.”

The name derives its meaning from the Matrix films, insinuating that its subscribers have chosen to take “the red pill” and recognize the true reality that they live in a female-dominated society. The main purpose of the thread is to provide an outlet for men to discuss topics such as ‘sexual strategy’ and ‘mastering game’ in an effort to court as many women as possible, but it also commonly verges into discussions about men’s rights.

So when I saw a post about a new program at Duke University called the Duke Men’s Project, a nine-week program aiming to facilitate discussions of male privilege, patriarchy and masculinity, I knew I had to write something about it.

The program was launched in September by Duke’s Women’s Center and it will be open to all male-identifying students on campus. According to organizers, the program was started as a way to engage men in working towards gender equality by encouraging men to discuss issues surrounding male privilege, such as rape culture, the language of dominance, pornography, gender diversity and intersectional feminism.

As expected, the idea has received a lot of criticism as a direct attack on all men. Perhaps my favorite line in the main post on The Red Pill expressed concerns that “[these programs] will never even recognize the existence of male issues if not in a perfunctory way, always and only for the sole purpose of dismissing them as relatively unimportant beside feminine imperatives.”

Criticisms like this are pretty far off the mark.

“Take a minute and listen. Most of the men who do not wish to be involved or are against programming like ours have not taken the time to really understand what we are working towards,” Duke junior and one of the leaders on the project Alex Sánchez Bressler told The Pitt News in response to these criticisms.

The project isn’t meant to attack men for their masculinity or to force them to deconstruct their identities. It’s an opportunity for male students to educate themselves about feminist issues — whether they are supporters, opponents or just curious about the movement — and to engage with notions about what it means to be masculine.

“Programs like our own are liberating for everyone, including men, since we encourage healthier alternatives to toxic masculinity that allow for more emotional expression, alternatives to violence and healthier relationships.” Bressler said to The Pitt News.

To understand this as an attack on men entirely misses the point. Feminism isn’t so much about men and women as it is about the unconscious understanding that what is “feminine” is weak and trivial, and what is “masculine” is strong and assertive. Just as there are dangerous stereotypes about what women should and should not do and be, this binary between masculinity and femininity also creates unfavorable stereotypes for men.

“[The goal of the initiative is for men to] critique and analyze their own masculinity and toxic masculinities to create healthier ones,” Duke junior Dipro Bhowmik told the Duke Chronicle, one of the four students leading the Project.

The criticisms aren’t completely wrong. At least in a sense, they echo the notion that men often face negative impacts from the way masculinity works and shapes society. Society dicates men should be strong, brave and pursue as many women as they choose. To fit outside of that mold means to be something other than a proper man.

Where critiques diverge is that they frame women and the feminist movements as disinterested with these problems because they affect men and not women.

But this isn’t the case — or at least it shouldn’t be.

While intersectional feminism is important for highlighting the experiences of all different kinds of women, it’s also just as important to incorporate all different kinds of men into the narrative, because feminism is about improving life for all genders.

“It is simply not possible to think about feminism today without thinking about male masculinity,” Todd Reeser, the director of the Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Program at Pitt, told The Pitt News. “The feminist project requires a concerted intellectual effort by men as well as those who do not identify as men.”

While there’s still a long way to go with feminism in regards to women’s issues, we’ve also come a hell of a long way. Sure, the wage gap sucks. My male colleagues still interrupt me in class, and I still get catcalled every time I walk down Atwood Street. But at least I, as a woman, and feminism, as a movement, recognize that these are big societal issues, and we have outlets to make a lot of noise about them.

There’s not really anything like this for men and masculinity.

The current patriarchal system is set up to benefit men more directly. Men are interrupted less, they hold more political and corporate power and their concerns are taken more seriously. But this system still comes with its own set of rigid social norms that men must uphold in order to be considered a worthwhile man. Pressuring men into such a firm box has real negative consequences.

A 2011 study by the American Psychological Association found that while women are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety or depression, men are more likely to experience antisocial disorders and develop substance abuse problems. It makes sense, since men are encouraged to keep quiet about their feelings and emotions, and it’s harder for them to find outlets to do so. They more commonly turn to substances like alcohol and drugs as a method for coping with pressures they’ve grown up thinking makes them weak.

While women are 20 to 40 percent more likely to be diagnosed with psychological disorders and to attempt to take their own lives, men committed 77.9 percent of the suicides in the United States in 2015. The reason for this large difference is uncertain — perhaps keeping with our two separate realms of masculinity and femininity, it’s much more common for men to use methods that will ensure death, such as firearms or suffocation, while women often resort to poison.

I won’t say that because of this we should stop focusing on women’s issues or even that men, on average, have a harder time than women in society. Institutional sexism recognizes men as superior and inherently more valuable, but on the flip side, it doesn’t acknowledge that men, like women, are complex creatures, capable of all the same feelings and emotions and affinity for femininity that women are.

While the goal of intersectional feminism is to incorporate all viewpoints when fighting patriarchy, perhaps these criticisms and forums like The Red Pill highlight that we haven’t done an active enough job of ensuring men’s voices are heard in feminism.

In a society, and especially a college culture, where sexual assault is running rampant, it’s important to acknowledge where these issues come from and work to tackle the root causes.

“We recognize that while sexual violence is perpetrated against people of all genders, the perpetrators of this violence are overwhelmingly male. We also recognize that the unhealthy and violent parts of masculinity enable the perpetration of such violence, either directly or indirectly.” Bhowmik told The Pitt News. “Therefore, talking about masculinity and encouraging men to express their manhood in healthier ways tackles one of the root causes of campus violence.”

This is exactly what the Duke Men’s Project aims to do by providing an environment where men can discuss these issues amongst themselves and come to terms with their own masculinities, accepting which parts are true and which parts have been cultivated by society, then take responsibility for how this affects women.

Duke’s Men’s Project and Pitt’s Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Program give me hope. It’s what we should be doing for all privileged groups in society, not just men. Heck, sign me up for the White Project, the Middle Class Project, the Protestant-Christian Project. Those are all discussions worth having.

Duke’s program isn’t using feminism to attack men. It’s about encouraging men to take their rightful and needed place in the movement of intersectional feminism so that society can move forward together. Leaving them out only fuels the misunderstandings that the network of the manosphere and The Red Pill is built upon.

Come on in, and don’t be shy — feminism is for the benefit of everyone.

Amber primarily writes on gender and politics for The Pitt News. Write to her at [email protected].