Oakland is a nomadic place. Students, businesses and trends come and go, but the one thing that stays the same is the architecture.

There’s a strange and rich history left behind in each home by the residents who pass through. Relics of Oakland’s past can be found in surprising corners of homes — a fireplace in the bathroom, a mural in the basement, a pong table hanging from a ceiling — yet often, there is no one to explain the origins of these curios.

Past tenants or landlords can offer insight into the lives of these Oakland homes. Between do-it-yourself music venues, multi-story nightclubs and even quiet dentist’s offices, Oakland homes have been just about everything.

The Bates Hardcore Gym

Through Oakland, across the Boulevard of the Allies and down the long Bates hill, there is a vacant home next to the Highway 376 on ramp. Neighbors are few, barring the one nightclub next door.

But as recently as two years ago, the soft hum of punk music would leak through the home’s walls on weekend nights. Students and fans of Pittsburgh’s do-it-yourself music scene would make the long trek through Oakland to experience a night of musical debauchery. The residents called it the Bates Hardcore Gym.

The tenants, four Pitt students who met through the University radio station, WPTS, knew they wanted to host shows when they started looking for homes in their sophomore year, but they didn’t know where to do it. Zach Luettgen, one of the four tenants, said it was difficult to find a space that would work.

“One of the largest problems with a house venue is obviously noise,” Luettgen said. “If you are in a heavily residential area, people call and complain.”

After searching long enough, they found the perfect spot.

“We found this cool house, but it was really far away,” Luettgen said. “We were so secluded. On the sidewalk you couldn’t hear even the loudest band. There was nothing.”

Over the next year, the Bates Hardcore Gym hosted shows as many weekends as it could, showcasing everything from soft acoustic solo acts to blaring hardcore punk bands — sometimes in the same night. Huddled in sweaty proximity, kids would mosh just feet from the bands playing, bashing into the walls and trying not to level the band members to the ground. Off to the side of the bands there was a bathroom without a ceiling. In the back, there was a circle of couches for showgoers to catch their breath. If they needed more of a break, there was always a calm gathering outside on the backyard patio. Never too much of punk fan himself, Luettgen said he liked to stand above the patio and admire the scene below.

“I enjoyed the fact that we provided that space for people,” Luettgen said. “It was good to see.”

As the Gym got more popular, people turned to Facebook for information. The hosts spread their plans through social media and word of mouth, and, quickly, the Bates Hardcore Gym was becoming a household name. The showrunners were not prepared for how popular the space would become.

Luettgen said after one year, the venue’s Facebook page hit over 1,000 likes.

“My roommate’s proudest memory was getting those likes,” Luettgen said. “In relative terms for a house venue, that’s pretty big.”

Eventually, the venue could be found on websites including Songkick and Bandsintown, bringing in both popular local acts such as Trash Bag, a punk outfit, and more well-established touring acts like the lo-fi band, Homeshake.

Popularity, or perhaps notoriety, became too much for the hosts midway through October 2015, and eventually the Bates Hardcore Gym came to an end. Luettgen said he was home alone washing dishes when a knock came on the door.

“It was someone from a state liquor, firearms and tobacco board,” Luettgen said. “It was basically them saying, ‘People have launched complaints against you,’ and ‘If I were you, I wouldn’t put on another show.’”

After posting a somber status declaring, “an indefinite hiatus” for shows on their Facebook page, the Gym members never put on another show. Luettgen said the group has all moved out at this point, and no one has occupied the space since.

“Only the ghost of the Gym’s past lives there now,” Luettgen said.

From Teeth to Tattoos

Tattoo and piercing spots litter Central Oakland. There are multiple parlors in South Side and two on campus, but there’s only one that does its work in retired dental cubicles.

Today, Empire Tattoo and an apartment above it share the duplex that was once Thomas Blaze’s dentistry office.

Blaze opened his dental practice at 230 Meyran Ave. in 2001 after purchasing the century-old home that now resides next to the vacant AD’s Pittsburgh Cafe. When he opened the practice, he didn’t expect to interact much with Pitt students and said they typically don’t seek out Oakland dentists.

“Undergrads go home to see their dentists, so I expected more local residents,” Blaze said.

When first looking at the home, Blaze learned an apartment had been split away from the downstairs unit years before. It came as an extra challenge to Blaze then, that now he’d be adopting a second profession — he would become a landlord.

Blaze said adjusting to the job wasn’t too difficult. It all came down to the residents.

“I quickly learned how to evaluate the tenants — if they were good kids,” Blaze said.

For the next few years, Blaze cleaned teeth by day and managed the property upstairs by night. After a decade, he decided he was ready for retirement, selling most of the dental equipment to another Oakland dentist and the downstairs space to the owner of Empire Tattoos.

Walking through the home’s basement now, there are empty file cabinets that once held patient records, used office furniture and old signs that read, “PARKING FOR DENTAL PATIENTS ONLY.”

The upstairs apartment has been through several renovations in the past 110 years, leaving bizarre hints to the building’s past. The closet has an unusual amount of depth due to its origins as a staircase. The bathroom is carpeted.

Haley Timple, one of Blaze’s current tenants, said people are always surprised at the oddities of the house, especially the bathroom.

“It’s the first thing that everyone notices when they come in here,” Timple said.

Today, most of the dental equipment has been moved to a new dental practice, but the tattoo parlor still uses the dental cubicles to do tattoos. Blaze said the house had been through many changes before he got there and would probably go through many more.

“It’s old,” Blaze said. “There’s a ring outside where you can tie a horse.”

Club Laga

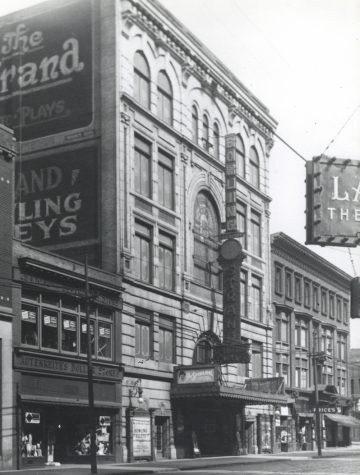

Farther up Meyran and around the corner is the Strand building, home to the Forbes IGA, which overlooks the heart of Pitt’s campus. Students today visit the building to buy groceries or grab a six-pack of beer from the owner, Ron Levick. Some students even live above the grocery store and rent their apartments from Levick as well.

Scanning the entrance to IGA, however, reveals a bit about the building’s history — a Macy Gray poster signed “Ron” with a heart, a clock with the signatures of Public Enemy and a photo collage of sweaty 20-somethings dancing under a stage. Levick wasn’t stocking shelves 15 years ago — he was running a nightclub.

Ron Levick leased the third floor of the Strand Building on Forbes in 1991, creating the Attic, a sports bar in a time he calls “the days of satellite TV.”

“People couldn’t watch things at home, so they came to the Attic,” Levick said. “We were packed for Penguins games and Steelers games.”

Seeing his success, Levick eventually leased the fourth floor in 1996 for Club Laga, an all-ages music venue, and then the second floor in 1999 for the Upstage, a dance club. Overall, he was managing three floors and 35,000 square feet of clubs.

Levick said Club Laga was a massive success. It had an industrial look, with exposed scaffolding, bright spotlights and a large dance floor. Upwards of 600 people would cram into the club to dance and drink. Levick said that multiple magazines called it one of the top college bars in the country. He disagreed, though, that Club Laga appealed to college students. Although he made a barricaded area where over-21 patrons could drink alcohol, Levick said it still didn’t keep college students around.

“Thing about Club Laga was that it was all ages,” Levick said. “There was a caged-off area where you could drink, so it tried to cater to everybody, but college kids didn’t want to come here because there were high school kids and older people.”

As time passed, Levick said, the kind of students that went to Pitt changed.

“It used to be people got drunk seven nights a week, but that doesn’t happen anymore,” Levick said.

When Levick noticed the falling attendance at shows, he eventually decided to move on to a different business venture. Oakland had a lack of grocery stores, and he had an overabundance of space, so in 2004, Levick closed the clubs, gutted the space and transformed the building into apartments and a grocery market.

“I wanted to cater to the Oakland community,” Levick said.

The apartments have large rooms, high ceilings and clean hallways. Students who live there, like senior Sneha Iyer, don’t see many remnants of the building’s action-packed past.

“We had no idea until one day it came up as an Instagram-suggested location,” Iyer said. “Club Laga came up, and we thought it was a joke.”

Levick has no interest in reopening any kind of club. He said he still gets emails saying he should bring Laga back, but to him it simply doesn’t make enough money anymore — groceries and apartments do.

“Instead of getting people drunk, now I sell produce,” Levick said.