“I mean, I voted, but why does it matter? London will never listen.”

When I asked my new Scottish friend about the United Kingdom’s recent election, he responded with pure ambivalence. He truly cares about the issues at hand, but he, like many other Scots, has long struggled with misrepresentation in government.

And this feeling isn’t just isolated to Scotland. Through my time studying abroad so far, I’ve come to the realization that me and my peers’ disgust toward politics isn’t uniquely American. The world is faced with the rising force of far-right populism, and while it may seem scary, we can look forward to the world that will be led by today’s young people.

And particularly, Americans today are more Scottish than they might think. To understand why — why Scottish attitudes toward England and the looming question of Brexit are analogous to young Americans’ feelings about the recent election — a bit of Scottish history is necessary.

The Kingdoms of England and Scotland have long struggled to find balance in their relationship, and fought a series of bloody wars from the 1300s to the late 1500s. This continued until 1603, when King James VI of Scotland became also King James I of England in the Union of the Crowns, a symbolic and strategic joining of the two kingdoms. It took until 1997 for Scotland to achieve home rule from England.

But home rule doesn’t mean full independence, and in 2011 Scotland finally voted on an independence referendum led by the Scottish National Party — and it failed. This made Scotland the first and only nation to reject an offer of independence from another.

Today, the threat of Brexit makes many Scots — a majority of whom voted to stay in the European Union in 2016 — rethink their votes against independence. People I’ve spoken with while abroad have voiced serious complaints that their voices simply don’t matter, and seem resigned to the fact that England will continue to rule them without concern.

And it’s this that strikes a chord with me. I, and so many people that I know, went out on Nov. 8 and cast our ballots for Hillary Clinton, and did so confidently. We didn’t believe Donald Trump could win office. We tried to make our voices heard — 55 percent of us voters age 18-29 voted for Clinton — but we were drown out by party politics and international interference into our election.

And much like Scotland, young America is now faced with leadership that they can’t affect and the growing shift of political debate from conservative vs. liberal to nationalist vs. globalist. The U.K.’s exit from the EU is eerily similar to Trump’s campaign calls for a border wall, institution of travel bans and exit from the Paris climate agreements — each of these things symbolizes nationalization.

The new far-right nationalists don’t seem to believe that cultural cooperation can result in benefits for all, or that membership in wider international organizations or treaties is worth their time — a scary thought for the average Scotsman, or young American.

But we can learn from each other, I think. Over 70 percent of voters age 16-24 voted to remain in the EU in 2016, and young voters overwhelmingly supported Scottish independence in 2014. And while votes for independence may seem nationalist, they in fact are votes in favor of self-determination, a clearly globalist point of view. These voters are the ones that would fight for other countries’ independences and freedoms, and would vehemently stand against the greedy.

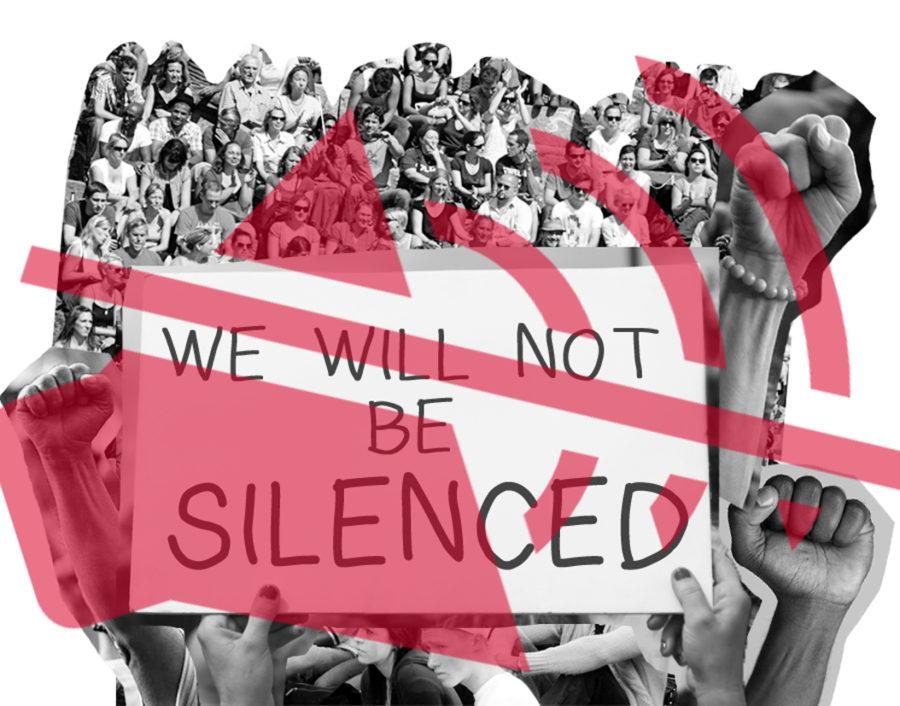

The scariest part about nationalism, or isolationism, is that to be against your country is to be alone, isolated. It’s why revolutions are so difficult to start, and why it feels like our young voices are so hard to make heard. We are yelling amid the crowd of an entire nation, but are met only with assertions that our president will make America great again.

We are not alone though. America, Germany, Holland, France and the United Kingdom are among the many nations faced with the newest wave of populist international politics. This seems frightening at first — more and more countries are showing isolationist tendencies and grappling with issues of adequate representation for their populations.

But in fact, there’s something comforting about all of it. What would be truly terrifying would be if young Americans were the only young demographic terrified of the threat of populism. But in Scotland and the broader United Kingdom, young voters mirrored their American counterparts in the fight against nationalism over the past few years, and similar trends are shown around the rest of Europe.

Of course, that’s not a comfort today, nor is it a comfort tomorrow.

It’s a comfort in the long run. Young people may feel slighted or alone up against their entire countries, where naturally older voters hold the power. But we are never alone.

Try as they may, politicians cannot take away from us the world we have at our fingertips, and try as they may, older generations cannot live forever. Soon, young people all around the world will be the ones with power, and hopefully we will be able to change a system that never favored us. This may be idealistic, but I hope that we can learn from the way our voices are ignored and change that oppressive system for the better.

Amid our own turbulent politics, a lot of Americans might not know why Brexit is so important, and I’m sure few of my peers know the details of Holland’s latest election. But these are more important than ever. If we want to continue building a more global, more cooperative world, we have to be invested in the things that affect us all, not just the nationalist view of what affects our fellow citizens. We must do what our elected officials cannot, and lead by example — one of the few things in our control.