Elliott Erwitt left his rented room at the downtown Pittsburgh YMCA in the fall of 1950, cameras in hand. The 22-year-old photographer walked up either Forbes or Fifth Avenue, documenting the people and places of the transitioning city along the way, before arriving at the Pittsburgh Photographic Library on the 30th floor of the Cathedral of Learning.

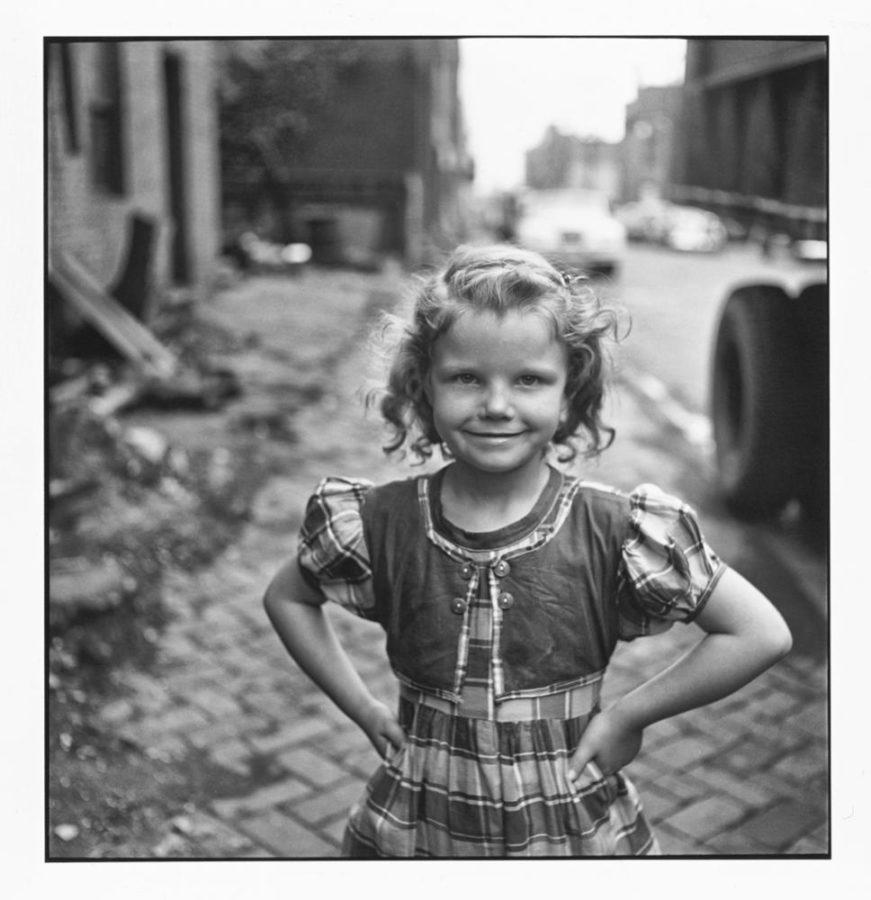

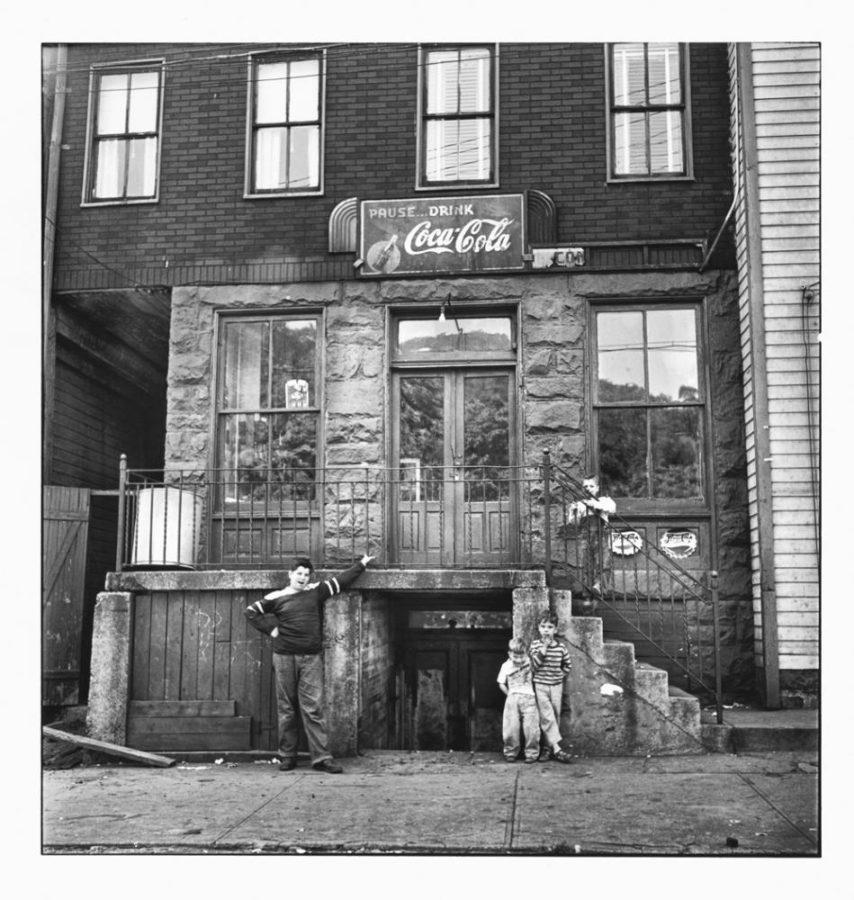

Erwitt documented scenes at parades and Pitt football games. He took portraits of workmen, beggars and children. He was tasked with documenting a city transitioning away from its gritty, purely industrial past — but his images were left largely unseen until now.

When Vaughn Wallace was a history major at Pitt in 2012, he was looking through photo archives at the Carnegie Library when he came across negatives, contact sheets and proofs created by Elliott Erwitt — by then a famous documentary photographer.

“It was pretty amazing to just get to be working with his original stuff,” Wallace, a former visual editor at The Pitt News, said. “It’s pretty cool to see his original annotations and captions.”

Library of Pittsburgh

Roy Stryker, best known for leading the Farm Security Administration documentary photography program during the Great Depression, was hired to build a photo collection — the Pittsburgh Photographic Library — that would show Pittsburgh in an era of transition. Stryker hired Erwitt as part of his team.

“[Stryker] had been hired to come and build up a core of photographers to document Pittsburgh in its post-World War II retooling, to put a new face on the city,” Wallace said.

Erwitt’s four month-long documentary project was largely forgotten after he received his draft notice in December of 1950.

More than 60 years after the photos were taken, Wallace was interviewing Erwitt for an unrelated project for Time magazine’s LightBox. He told Erwitt, now in his 80s, about the Pittsburgh archives containing hundreds of his photos. Wallace and Erwitt worked together over the next few years to compile and edit the photos, recently publishing them in a book — “Pittsburgh 1950.”

The project was commissioned by the Allegheny Conference on Community Development as business leaders and community members were worrying about losing talent and population in Pittsburgh after World War II. Their goal was to have photographers document four big initiatives to improve the city — getting rid of the smoke, cleaning up the water in the rivers, stopping the flooding and fixing blighted areas, according to Bill Flanagan, chief corporate relations officer at the conference.

Library of Pittsburgh

“It eventually led to a treasure trove of photography — of the community, of the big civic changes, of the transformation that was underway in Pittsburgh at the time,” Flanagan said. “[The conference] was doing something that was really big, something that had never been done before. They wanted to make sure there was a photographic record of it.

Wallace spent much of his junior year at Pitt looking through that record and trying to learn more about Erwitt’s role in the project. Wallace said Erwitt’s work documents Pittsburgh’s transition away from a dirty, industrial city, but also focuses on the people living here at the time of transition.

“There’s a lot of straight documentary of a city in transition — buildings being torn down, new highways being built,” he said. “But interspersed in that is a lot of what’s notable in Elliott’s career — his humanist eye.”

In addition to the human focus of his work, Erwitt’s photos also document the physical transition of the city as well — specifically the transformation of the Point into Point State Park as Pittsburghers know it today. This development was one reason the Allegheny Conference on Community Development hired Stryker and his photographers.

The redevelopment of the Point from an industrialized area to a park was a focus of the Allegheny Conference’s effort to rebrand Pittsburgh, said Gil Pietrzak, who runs the Pittsburgh Photographic Library in Carnegie Library’s Pennsylvania Department.

“[The conference] came up with this idea of a photo collection to, more or less, use it as a PR tool to attract business and industry to come here and people to live here,” Pietrzak said.

Library of Pittsburgh

Wallace notes that Stryker — who was leading the project for the Allegheny Conference — filed many of the Pittsburgh Photographic Library’s photos in the “kill file” if they didn’t meet the project’s mission. Stryker was known to frequently hole punch the negatives he didn’t like, rendering them useless. For whatever reason, he didn’t do that in Pittsburgh, allowing history buffs like Wallace to dig through the photos decades later.

“Pittsburgh is a really awesome city in terms of being able to really see and feel its history,” Wallace said. “As a history buff it was a really neat city to live in.”

As Wallace points out, Erwitt’s Pittsburgh work focused on the people in the city more than the developments. Many of his photos are found in the human interest category in the library’s collections, which Wallace calls “an ironic understatement of Elliott’s timeless visual approach to the world” in an essay at the end of the book.

“I think Pittsburgh has a sound,” Wallace quotes Erwitt in the essay. “Pittsburgh conjures up something. Maybe it’s just the name — but I don’t know Springfield would do the same.”

“Pittsburgh 1950” by Elliott Erwitt is available through Gost Books for $65.