Students studying on the ground floor of Hillman Library Saturday afternoon may have been a bit surprised to hear African drumming, poetry readings and the sounds of stamping feet and clapping hands coming from the Digital Scholarship Commons room.

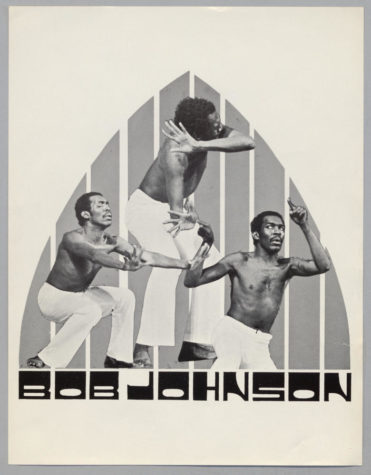

All this performing was in honor of Robert Johnson, a Pittsburgh-based artist and former Pitt Africana Studies faculty member who died in 1986. The event — attended by about 120 of Johnson’s family, friends, colleagues, students and members of Hillman’s library staff — also celebrated the addition of the Bob Johnson Papers — a collection of documents relating to Johnson’s work at the university and outside of it — to Pitt’s special archives collection.

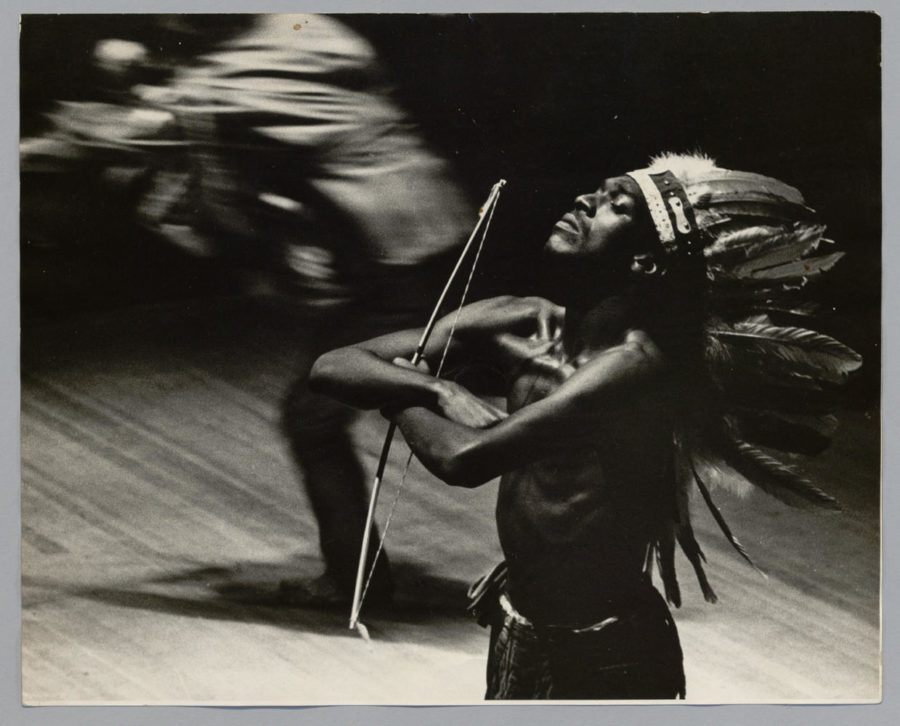

Bob Johnson was a Brooklyn-born dancer, choreographer, actor and director whose career and life’s work were based in Pittsburgh. Johnson founded the Pittsburgh Black Theatre Dance Ensemble and taught in the Africana studies department at Pitt from its early years in the 1970s until his death in 1986. Johnson also toured nationally and internationally as a dancer with Sun Ra and his Arkestra.

The Bob Johnson Papers include poems written by Johnson, posters, programs for plays he helped create or starred in and photos of classes he taught at Pitt. Johnson’s son and daughter, Samba Johnson and Marimba Johnson-Bright, donated the collection.

William Daw, liaison librarian to Pitt’s theatre arts department, worked on putting the collection together and organized the event celebrating its release. He said Johnson was part of the larger Black Arts Movement throughout the 1960s and 1970s and through it influenced the Pittsburgh African dance community and the University’s dance, theatre, history and Africana studies departments.

“I don’t think that there is any argument that Mr. Johnson led a vastly unique life, traveled the world, performed all over the world, but his home was here in Pittsburgh,” he said.

Johnson-Bright said they chose to donate their father’s papers to Pitt because of Johnson’s involvement in the Pitt Africana studies department where he did most of his life’s work.

“His start was at the University of Pittsburgh, and this is where he passed, and all of his life’s work was here in Pittsburgh, particularly in the Oakland area,” Johnson-Bright said. “It was best fitted that [the collection] came here for students and the community to research his information.”

A display of various pieces of Johnson’s collection — including photos, letters and programs — was situated at tables for guests to examine Saturday. Large pictures of Johnson and his dancers were scattered around the room. Televisions continuously played footage of Johnson’s choreography, including one of him dancing alone on roller skates.

Johnson-Bright said her mother started creating a collection for her husband in 1995. She enlisted a family friend who worked as an archivist to help put it together, but due to family issues and the death of her mother the project was ultimately put on hold.

Oliver Byrd, one of the speakers at the event, reflected on Johnson’s love for dance and the independent approach he took when crafting his choreography.

“Johnson would always say, ‘I just want to dance. I don’t want to have to dance to somebody else’s tune,’” Byrd said.

Another speaker, Malaya Rucker, recited one of Johnson’s poems “I am the original dance machine.” She performed accompanied by drums, a horn and the energized clapping and snapping of the audience.

“I am the original dance machine/There is no imitation of me/You are the original dance machine,” Rucker recited.

Johnson-Bright said her father loved Pitt and helped raise money for the African-American heritage room in the Cathedral of Learning. He was also extremely passionate about teaching.

“My father was really dedicated to his students,” Johnson-Bright said. “He impressed upon mentoring students and just being a part of the African-American community.”

Johnson-Bright said she was emotionally overwhelmed by how many people showed up to celebrate Johnson’s work.

“It’s is a true testament on how my father impacted so many people’s lives,” she said.

Beyond research, Samba Johnson said he hopes the papers and his father’s legacy will inspire those who want to learn about dance and black history at Pitt.

“We hope that his legacy will be shared with incoming [first-year students] and inspire people who want to learn more about dance, want to learn more about black history at the University of Pittsburgh in the early ‘70s … to learn about a man’s passion for diversity and to share his love with everybody he came in contact with,” Samba Johnson said.

Samba Johnson said if their father were able to be at the event he would be thrilled to be honored by the people he spent years working with and teaching.

“He would be very excited, very humble and just very appreciative that the University of Pittsburgh gave him an opportunity in the early ‘70s where a lot of African Americans didn’t have the opportunity to do what he did,” Samba Johnson said.