Pittsburgh Pipers: The forgotten champions

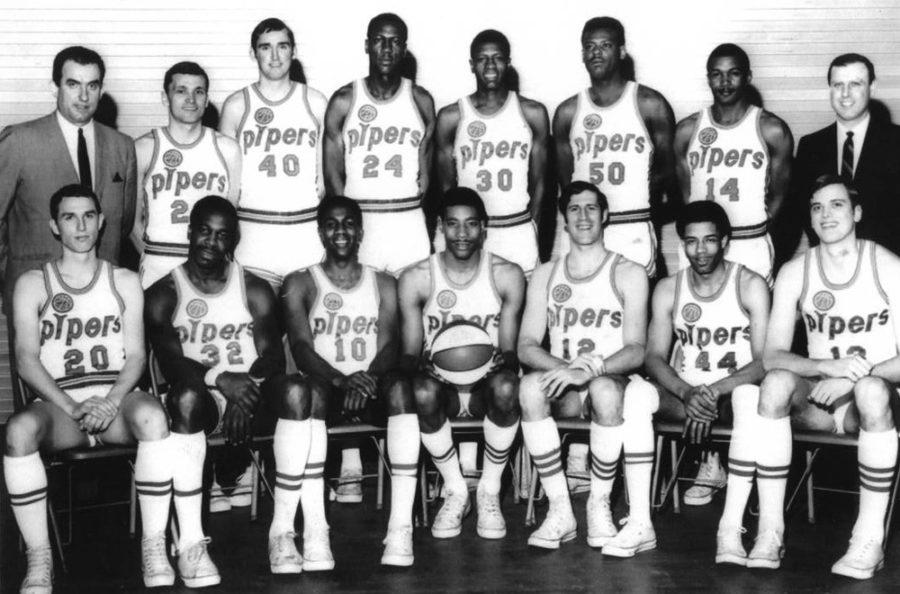

The Pittsburgh Pipers were the ABA champions in 1968. Now, 50 years later, the players reflect on their time on the team — a footnote in steel city sports history. (Photo courtesy of Heinz History Center)

November 8, 2017

Pittsburgh is often considered one of the premier sports cities in America — laden with a prosperous history of baseball, football and hockey championships. But the city was once home to a championship basketball team, too — a small blip in the timeline of Steel City sports.

The Pittsburgh Pipers were the inaugural champions of the American Basketball Association in 1967 — 50 years ago this year. They won the league’s first title in a seven-game series against the New Orleans Buccaneers.

For Steve Vacendak, one of the guards on the team, the seventh and final game against New Orleans stands out as a moment of hope and accomplishment.

“I think the final game in Pittsburgh was such a wonderful conclusion to the season to have the fans turn out like that and for us to win in such a dominant manner,” Vacendak said. “That last game stands out because it’s what we had been working for all season.”

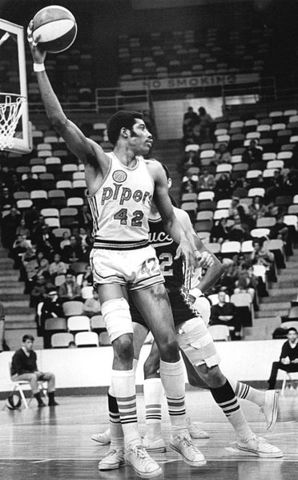

Connie Hawkins lead the Pipers to their ABA championship in 1968, leading the team with 26.8 points per game. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The summer of ‘68 would be the only one in Pittsburgh for the Pipers before they moved to Minnesota when Minnesota-based lawyer Bill Erickson purchased a majority share of the team. The Pipers replaced the Minnesota Muskies, another one of the ABA’s founding teams that failed because of lack of fan support.

The team returned to Pittsburgh in 1969, but never found the same support or success. While they are often overlooked today, the ‘67-’68 Pipers were a seminal team in a league that would eventually help change the way basketball is played.

During its first season in 1967, the ABA had 11 teams in several markets the NBA hadn’t reached yet. The teams included New Orleans, Houston, Denver and Oakland in the Western Division, and Minnesota, Indiana, New Jersey and — of course — Pittsburgh in the Eastern Division.

The league was a new brand of basketball in comparison to its counterpart in the NBA — which was established in 1946 — defined by an exciting style of play. Ira Harge, who played center for the Pipers during their championship season, recalls the innovations the ABA introduced — including its iconic red, white and blue colored ball.

“It was easier to track [the ball],” Harge said. “You didn’t have that big brown thing floating in the air. We had more of a running game, a fun game. Our teams were running up and down the floor with this red, white and blue ball and shooting the three pointer.”

The 3-point shot was first introduced in the less successful American Basketball League in 1961, and was forsaken when the league dissolved in 1963. The ABA reintroduced the idea in 1967, along with the first dunk contest — two ideas the NBA would eventually adopt.

In its inaugural season, the ABA drew a respectable total attendance of 1,200,439 compared to the NBA’s 2,935,879 the same year. Some ABA franchises, like the Indiana Pacers, had impressive turnouts. The Pipers, though, weren’t exactly packing the Civic Arena with fans.

Jim Jarvis, who played point guard for the Pipers, remembers the unimpressive crowds the Pipers drew in the first season, but he says it never bothered him.

“The crowds were not that big, but we had a lot of good guys on that team,” Jarvis said. “The crowd situation was not something I remember being a big issue with us. We just loved to play basketball.”

The first Dr. J

Fans who did attend were treated to a show from one of the best teams in the league. The Pipers started the season strong with a 24-12 record by the end of December, thanks in large part to star player Connie Hawkins and head coach Vince Cazzetta.

Cazzetta only coached the Pipers in that first season and was forced to leave after a contract dispute led to his resignation. He passed away in 2005 on the 37th anniversary of the Pipers’ ABA title win. His players respected him and praised his ability as a coach.

Connie Hawkins won the MVP trophy in the 1968 ABA championship. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

“I don’t think Vince played the game, but he understood the game,” Jarvis said. “He had to have the ability to get across what he wanted to have done and have the players do it even though there was a difference in personality on the team.”

Two guards from that ‘67-’68 Pipers team, Arvesta Kelly and Steve Vacendak, also remember Cazzetta as a great leader and coach.

“He was a tremendous communicator, and he knew the game,” Kelly said. “He knew the Xs and Os of the game.”

Vacendak said the coach’s experience in raising children “kind of helped him in dealing with [the players].”

“He was a great father, and I think he had wonderful relationships with his children and his entire family,” Vacendak said. “He had the gift of being able to communicate … in a way that made you accept it and want to execute it.”

Just as the season was reaching its halfway point, the Pipers made sweeping changes to the roster, ending the season with just four of the players who began it. But Hawkins, one of the best players in the league, led the team through the personnel mix-up.

Hawkins led the ABA in scoring that first season, and is enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame for his accomplishments in the ABA and later the NBA. He passed away this year on Oct. 6, but his teammates have clear memories of his game.

“He was really the predecessor to today’s game with his physical abilities,” Jarvis said. “He could run the floor, he could rebound. He wasn’t a deep shooter, but he could turn and face the basket.”

Jarvis, Harge, Vacendak and Kelly all remembered Hawkins the same way — as the best player they ever shared the court with.

“He’s the top of the list,” Jarvis said.

“I always thought Connie was the best thing that happened, not to [disparage] Julius Erving or Rick Barry or anybody,” Harge said.

“Connie Hawkins was the first real Dr. J,” Vacendak said.

“He’s definitely the best ball player that I’ve ever played with,” Kelly said.

Kelly also remembers Hawkins’ struggles with a leg injury during the second half of the ‘67-’68 season.

“Connie was the one that really kind of spearheaded everything. And I think he was hurt, there was something wrong with his leg, but he played and he said, ‘Come on, we got to win this,’” Kelly said.

If Hawkins was bothered by injuries, it didn’t show. In the second half of the season, the Pipers found momentum, finishing with a 54-24 record. Hawkins averaged 30.9 points per game over the last 30 games and won the first ever ABA MVP award.

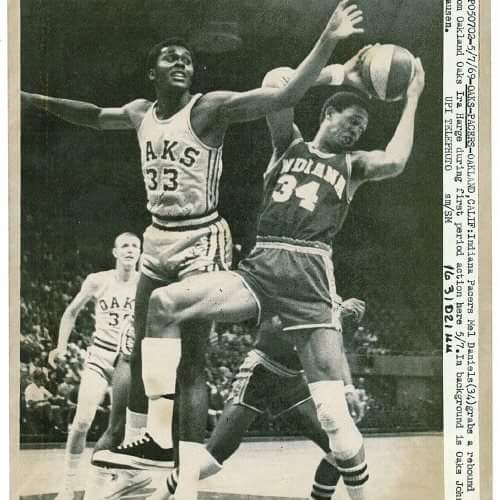

Harge was one of the players who was traded during the midway point, ending up at the Oakland Oaks. That trade meant he was forced to match-up against the 6-foot-8 star when the Oaks faced off against the Pipers.

“He gave me a little fake and he went by me and he said something to the effect of ‘Well, I’m glad you didn’t stay with us in Pittsburgh ‘cause here I am on one leg and I went by you,’” Harge said.

“Did you see me block that shot?”

The Pipers beat the Indiana Pacers and Minnesota Muskies in the Eastern Division playoffs to reach the finals against the New Orleans Buccaneers. In the finals, Pittsburghers jumped on the bandwagon.

Ira Harge was traded to the Oakland Oaks mid-season and matched up against Hawkins and the Pipers. (Photo courtesy of Ira Harge)

“I remember that we did have a pretty good crowd for that series,” Jarvis said. “I don’t know if they gave away tickets or what.”

“Those last games that we played, the arena was packed,” Kelly added.

According to Kelly, the final series against the Buccaneers was tension filled and — on one occasion — that tension led to a fight with a fan.

“We were going into the locker room and one of the fans was heckling Art Heyman,” Kelly said. “Art Heyman punched him and we had to get the police to give us an escort out of the stadium. I will never forget that as long as I live. Art was always doing something.”

Heyman was famous for his eccentricity. Jarvis, who roomed with him on the road, recalled a habit Heyman had after games.

“Art was the guy that constantly needed praise. After a game he’d come back in the motel room late and wake me up and say, ‘Gosh, what did you think of that pass I made, wasn’t that a great pass? Did you see me block that shot?’” Jarvis said.

“He’d call you up at two or three in the morning, I’m saying ‘dude go to bed,’” Kelly said.

Even with Heyman’s antics and Hawkins’ leg injury, the Pipers pulled through to win in game seven against the Buccaneers, beating New Orleans 122-113. Hawkins was the MVP of the series.

Forgotten legends

The Heinz History Center has a small display case dedicated to the championship Pipers squad. (Photo by Aaron Schoen | Staff Photographer)

Pittsburgh hardly had a chance to celebrate the new champions — there were no parades, no rallies. The players left after game seven and most never returned to the Steel City.

“I think most of us left Pittsburgh during the summer months and weren’t back there, so soon as the season was over you loaded up your car and went across the country,” Jarvis said.

By the start of the next season, the Pittsburgh Pipers were the Minnesota Pipers. The franchise never capitalized on the success of its first year in Pittsburgh.

The Pipers weren’t able to draw any bigger crowds in Minnesota, and Erickson and co-owner Gabe Rubin lost more than $250,000 on the team. Rubin decided to move the team back to Pittsburgh at the end of the ‘68-’69 season. By that time, Hawkins was in the NBA and support for the team had further died down.

The team changed its name in an attempt to create a buzz around the team. By 1971 they were the Pittsburgh Condors, but the name change failed to attract more interest. According to Kelly, the move in 1968 may have been the death knell for professional basketball in Pittsburgh.

“We left and then we came back without Connie, and that was a big reason why the team did not succeed,” Kelly said.

Vacendak agrees with Kelly. He thinks the franchise even had potential to join the NBA through the eventual NBA/ABA merger in 1976 if they had stayed in Pittsburgh.

The ABA championship trophy sits in the Heinz History exhibit. (Photo by Aaron Schoen | Staff Photographer)

“I don’t think there’s any question about it,” Vacendak said.

Instead, the Condors never even made it to 1976. The ABA shut the team down in 1972 due to the lack of fan support.

It’s been 50 years now since the Pipers won that title, and all the City of Pittsburgh has to show for it is a small display at the Heinz History Center. Even the Basketball Hall of Fame makes no mention of the Pipers, Kelly noticed.

“The last time that I was at the Basketball Hall of Fame, they didn’t even have a picture or nothing about the Pipers and us winning the first championship of the ABA,” Kelly said.

Now, Kelly feels like the team he spent so long playing for has been left behind by history.

“It’s like we were the forgotten team,” he said, “I don’t understand that, when we were the first team to win the ABA championship.”