‘Dandy Andy’ tour takes a look at Warhol’s queer history

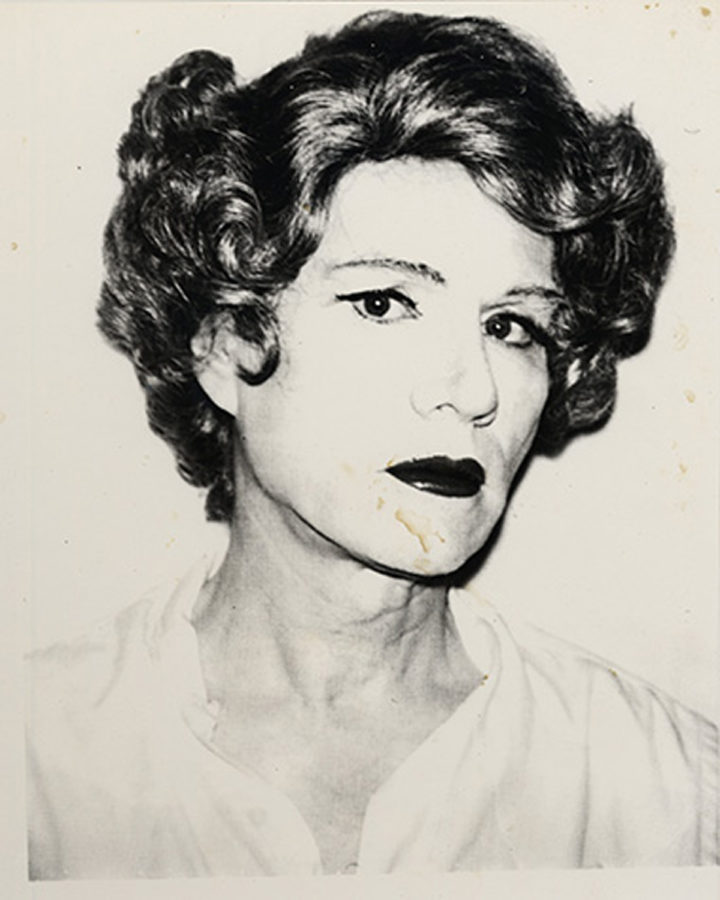

The Andy Warhol Museum’s “Dandy Andy” tour focuses on Warhol’s identity as a gay man in relation to the gay rights movement in the United States. (Photo courtesy of Andy Warhol, Small Acetate (Self-Portrait in Drag), 1980, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

Most people have heard about or seen Andy Warhol’s work at some point in their lives, from his renditions of the “Campbell’s Soup Cans” to his famous pop art portraits.

And Warhol himself is just as recognizable today to American audiences as his popular art. But while literature is constantly updated on Warhol’s professional career as an artist, there are still chapters of his life that go unmentioned.

The Dandy Andy tour, which the Andy Warhol Museum on Pittsburgh’s North Shore began in 2014, looks to bring to light the hidden history of Warhol’s often-unnoticed romantic relationships and queer art. The tour differs from regular museum tours by allowing visitors to learn more about Warhol’s boyfriends, his life as a gay man in New York City and how his art was subsequently influenced by the men in his life and the queer community.

Grace Marston works as a gallery educator at the Andy Warhol Museum and came up with the idea of the monthly tour focusing on the artist’s personal life. She said her journey into uncovering the truth to Warhol’s queerness began by looking at his romantic relationships.

“I began doing research into Warhol’s boyfriends and saw that these relationships spanned his entire life,” Marston said. “And they had all contributed to his artwork in some way.”

Edward Wallowitch was a Pittsburgh-born photographer who met Warhol in New York and would later have a relationship with him in the late 50s. Many of Warhol’s early drawings were based off of street photographs produced by Wallowitch, including his early work with the Campbell’s soup can.

Similarly, in the ’60s, Warhol filmed poet and boyfriend John Giorno for a number of film projects, including his 1963 film titled “Sleep.”

Warhol’s creative muse in the ’70s and partner of 12 years collaborated with and edited two of Warhol’s films, even directing “Andy Warhol’s Bad.” But one of the only mentions of Jed Johnson within the Warhol Museum is a small placard in a glass case on the second floor next to a few pages of his handwritten letters.

The placard explains how Johnson started off as a telegraph delivery boy for Warhol, then worked as his assistant and would later visit Warhol every day while he was in the hospital after being shot by author Valerie Solanas in 1968. What the text does not mention is that Johnson lived with Warhol for almost a decade before their breakup in 1980.

The men in Warhol’s life were often subjects of his photographs and films, as seen in his polaroid depictions of the nude male form. These men were friends, creative partners and actors in his films.

Programs Coordinator Paul O’Brien said when observing Warhol’s behavior, it is apparent he had a method for getting the attention of handsome men and forming partnerships — often asking to film, photograph or draw them in order to start a dialogue.

“You can really see the template for how he would produce relationships,” O’Brien said. “He was really self-concious and really shy, but he was confident in his art. And he would use that as a sort of flirting.”

When speaking about these relationships on the daily tours, museum educators encountered an unusual challenge when considering the authenticity and presentation of Warhol’s work.

For O’Brien, it was all about showing Warhol’s art the way he would have wanted. That is, letting the work speak for itself.

“Andy answered most interview questions with, ‘I don’t know. What do you think?’ He didn’t want to tell people how to take the artwork,” O’Brien said. “So we thought, without coloring how people are looking at the artwork, how can we make sure this information is put out there?”

The Dandy Andy tour offered a perfect alternative educational opportunity for those looking to “color” in the spaces of Warhol’s life and safely engage in conversations about the LGBTQ+ experience.

“Rather than queering the artwork and doing a particular read of the artworks, what we could do is have a chronological order of the contemporary gay rights movement,” O’Brien said. “So we can put a cultural context to the work he is producing.”

And not only does the tour allow for Andy’s queerness to be more than just a footnote to his story — it also presents the gay rights movement to guests as they descend through the chronologically curated works.

“For the queer community, it was amazing to be able to see drag queens and gay men on screen,” Marston said. “So even though he wasn’t explicitly political, he was being himself and gave others the opportunity to be themselves.”

If there’s one thing Andy is most famous for doing, it’s unapologetically expressing himself and his art. He captured the world’s imagination while he was alive, and he continues to do so today.

Christopher Harding, a customer care specialist at Panther Central, went on the tour last February. For him, the tour made him consider how Warhol’s sexuality factored into his art and shed some much needed light on the artist himself, making him seem like any other person who fell in love and had romantic relationships throughout life.

“I began to see more of Andy, the person, and all the vulnerabilities he had,” Harding said.

The Dandy Andy Tour runs at 3 p.m. on the last Saturday of every month at the Andy Warhol Museum, 117 Sandusky St. in Pittsburgh’s North Side.