Prisoners deserve to be evacuated too

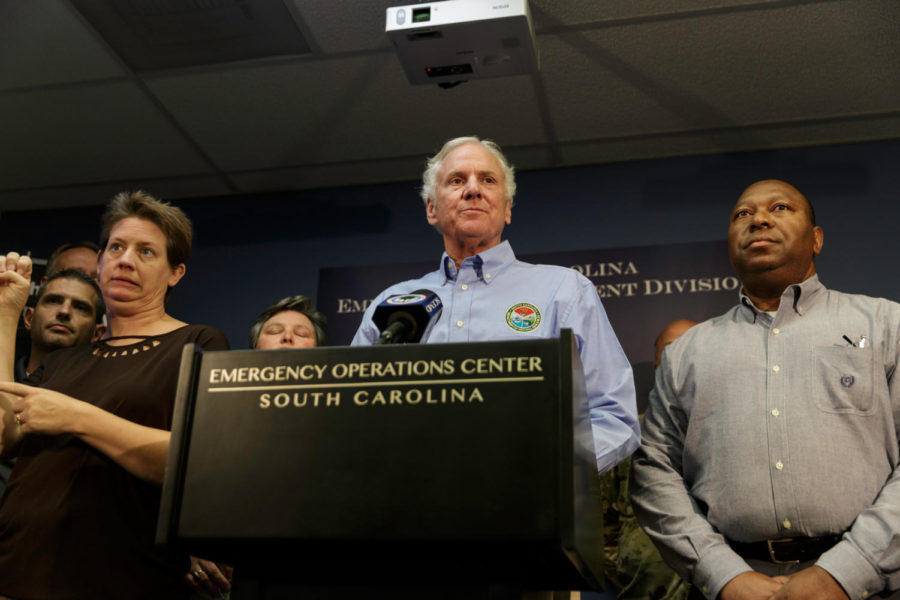

Several South Carolina correctional facilities remained occupied during Hurricane Florence despite mandatory evacuation orders from Gov. Henry McMaster. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

September 27, 2018

As Hurricane Florence battered the East Coast and citizens evacuated in droves, more than 600 men in a minimum-security prison at MacDougall Correctional Institution in South Carolina remained at the location, despite mandatory evacuation orders from the state’s governor Henry McMaster.

“Right now, we’re not in the process of moving inmates. In the past, it’s been safer to leave them there,” Dexter Lee, spokesperson for the South Carolina Department of Corrections, said in a statement Sept. 10.

But this simply isn’t true. In past storms, prisoners have suffered when they haven’t been evacuated, and during Florence two people in custody died while being supervised by two police officers. The issue isn’t one of safety — it’s one of morality.

Incarcerated persons’ lives should not be left in the hands of Mother Nature during natural disasters, especially when there are mandatory evacuation orders, which apply to all citizens. Shaundra Y. Scott, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union-South Carolina, agreed.

“This storm is slated to be one of the worst we have ever seen, and if Gov. McMaster truly does not want to ‘gamble with the lives of the people of South Carolina,’ he needs to make sure that the prison system is up to par, or evacuate the inmates just as he has ordered the rest of us to do,” the statement read.

When Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast in 2005, 7,000 prisoners from the Orleans Parish Prison were left behind, while thousands of others followed mandatory evacuation orders — including the sheriff and correctional officers responsible for the prison. Sheriff Marlin Gusman announced that the prisoners would have to “stay where they belong” and ride out the storm from inside OPP, where they had generators to keep essential functions going.

By the time Katrina hit the next day, the generators had failed. At the same time, at least 50 levees designed to keep the cost from swallowing New Orleans broke, and OPP began to flood. According to inmates kept at OPP in 2005, water on the ground floor was chest deep just two days after officers left.

Though Sheriff Gusman claims no prisoner deaths occurred during Katrina, witnesses inside the prison claim they saw dead bodies floating in the floodwaters. They had not had access to clean water or food for days and had no help from prison staff.

“They left us to die there,” Dan Bright, an inmate at OPP during Katrina, said.

It took four days for buses to finally arrive at the prison, during which time thousands of records had been destroyed, including physical evidence that could have exonerated those waiting for an appeal. Some of the inmates at OPP weren’t even convicted criminals — they were waiting trial and couldn’t afford bail.

Hurricane Katrina set records for the levels of destruction, causing more than $100 million in damage. Few had time to prepare, as the storm changed course to hit New Orleans — and the OPP — three days before landfall.

But Hurricane Florence was different. Officials knew how destructive Florence had the potential to be, and although floodwaters have yet to receed, it appears as though no one has learned their lesson from OPP. Thirteen years after 7,000 men were left to die in Louisiana, similar calls were made in South Carolina, repeating the mistakes of 2005.

While Gov. McMaster urged residents to evacuate, incarcerated persons died. Two women who were involuntarily committed mental health patients died in South Carolina when the sheriff’s vehicle they were shackled to was overrun by floodwaters on Sept. 18. This occured after the deputies escorting the women chose to drive around a barricade and onto a flooded road.

The two deputies were able to free themselves and attempted to rescue the women, but could not open the doors to the van because of how quickly the waters rose. The women were unable to free themselves because they were shackled to the floor.

The deaths of the two South Carolina women indicate that officials have little regard for the lives of the incarcerated. Prisoners are left with limited protection against the elements throughout South Carolina. A short statement released from representatives of SCDC said inmates were given food, water and other essentials to ride out the storm, although it took multiple calls and emails from both The New Yorker and families of inmates to get a response from SCDC.

Whether awaiting trial in Orleans Parish Prison during Hurricane Katrina or being transported in a sheriff’s van as a mental health patient in South Carolina or even serving time as a convicted felon, the state and federal governments alike have a responsibility to evacuate inmates in the event of natural disasters.

Subjecting inmates to possible days spent in floodwater without food, without drinking water and without help will lead to death. It is not just irresponsible and unethical to not evacuate prisoners — it’s immoral.