Stop colloquializing mental illness

October 21, 2018

While browsing the internet recently, I came across a website selling a T-shirt that read, “I have crippling depression.” After ranting about it to whoever was unfortunate enough to be within earshot, I asked myself who would possibly pay money to wear such a thing. Then it occurred to me that I could think of several people, in my immediate social circle alone, who would proudly do just that.

We live in an age in which mental health is discussed more openly than ever before — higher numbers of people are receiving treatment, the stigma associated with psychiatric disorders is increasingly receding and scientific advancements continue to illuminate the biology of the brain, giving us new information as to how the mind works and how to best accommodate abnormalities. Unfortunately, this positive evolution has also resulted in the casualization of mental illness.

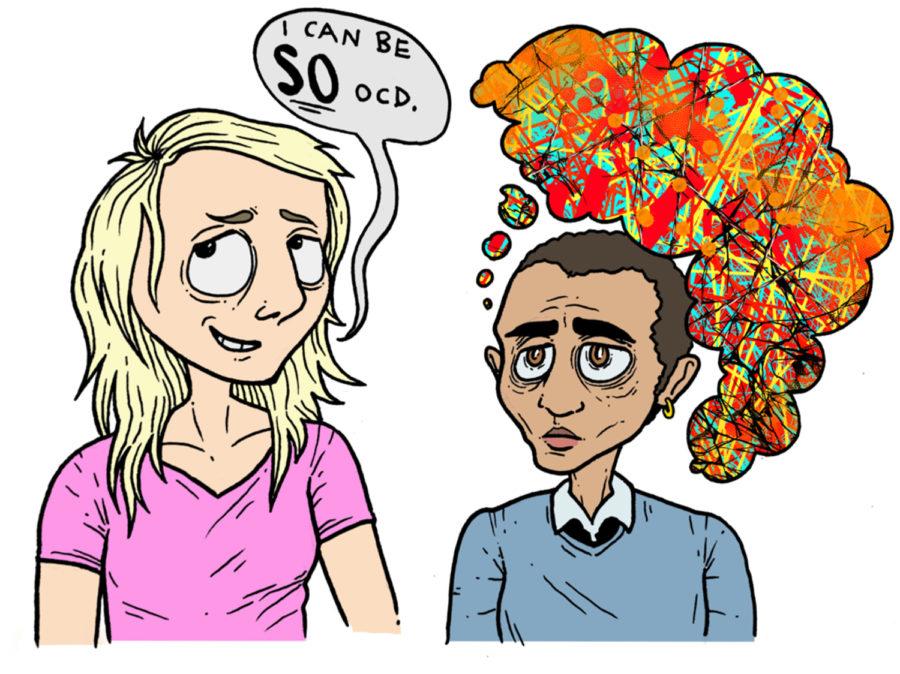

For instance, an overly neat person might be described as having OCD, or someone inconsistent or moody will be referred to as being bipolar. Saying things like, “That makes me want to kill myself” or “I wish I were dead” is not only common — it’s usually understood as typical millennial humor.

These kinds of generalizations trivialize the constant struggle that accompanies life with a mental illness, while also perpetuating stereotypes associated with certain conditions. Additionally, it becomes difficult to tell who actually needs help and who is just speaking in hyperbole. As such, these seemingly harmless colloquialisms jeopardize mental health treatment, as well as the progress society has made in taking these issues seriously.

A boy on Tinder once mansplained “dark humor” to me after he failed to pick up on my own sarcasm, so I’d just like to clarify — I get dark humor. I’m usually all for it. But mental health stopped being a joke for me a long time ago, because it got too real to be funny. I couldn’t say, “I’d rather die than do that,” to my parents anymore when I wanted to be dramatic. Before, they’d roll their eyes — now, the inpatient facility is only a 10-minute drive away.

Once I realized the effect those formerly harmless expressions started to have on the people close to me, I couldn’t unsee it — the stricken look on my mother’s face, my best friend’s concerned eyes. Careless dropping of the words “depressed,” “anxious,” “suicidal,” twisted grotesquely in my ears. It hurt that my reality, my everyday, seemed to be just an abstract idea to so many other people.

More than 43 million Americans deal with some sort of mental health or substance abuse condition. 75 percent of mental illnesses begin by the age of 24. One in five young adults will be affected by a mental health condition during college. Suicide is the third leading cause of death on college campuses.

Suicide rates are increasing on a national level, rising 30 percent since 1999. A 2015 survey study in Boston found that at least one in five college students experiences suicidal thoughts, and 9 percent confirmed that they had attempted suicide. Unfortunately, while suicide has developed into a domestic epidemic, its colloquial usage continues to crop up in everyday conversation, detaching it from its tragic nature and reducing it to a figure of speech.

According to the psychologist Howard Samuel, who founded the Los Angeles rehabilitation facility The Hills Treatment Center, laughing about mental illness not only minimizes a condition, but degrades sufferers in the process.

A passing comment you make could hit the person next to you like an invisible fist, and you might not ever know. You can forget you said it, but maybe one of your friends can’t. It’s still really hard to talk about mental illness, and hearing it being treated as a joke makes it even harder.

I understand that sardonic, bleak wit is a defining attribute of the millennial-Gen Z generation, as my friend from Tinder so kindly explained to me. But, as always, there’s a difference between being funny and being thoughtlessly hurtful. Every time you laugh about mental illness, remember how many people cry about it — and that they’re a lot closer than you think.

Kelly writes primarily about social and cultural issues for The Pitt News. Write to Kelly at [email protected].

If you or someone you know is in need of immediate mental health assistance, call the National Suicide Prevention hotline at 1-800-273-8255. If you’d like to seek further mental health resources, call the University Counseling Center at (412) 648-7930 or the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration hotline at 1-800-662-4357.