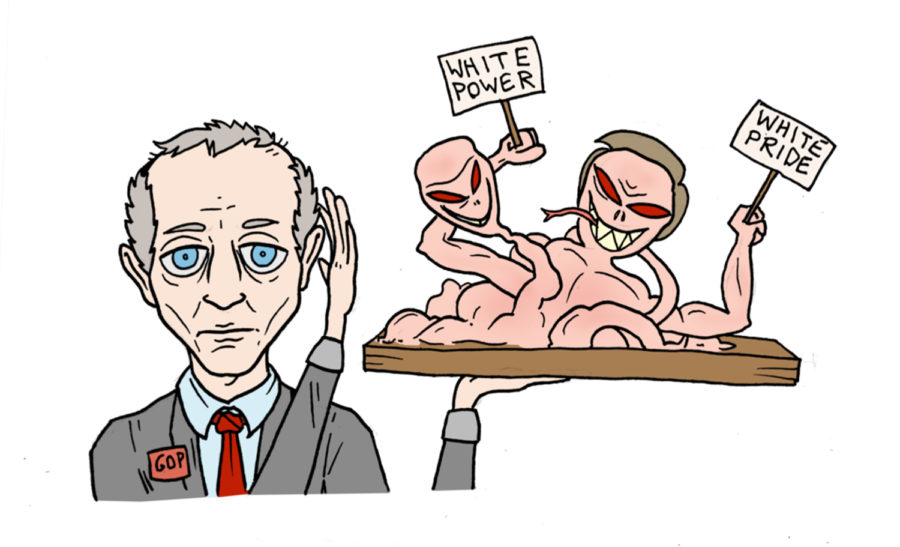

The GOP’s white nationalism problem

November 8, 2018

The 2018 midterm elections were an informal referendum on many things, from President Donald Trump’s administration’s policies to Republican attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

But one of the issues the Republican party focused on in these midterm elections was immigration — and Republican rhetoric on this issue continued to reveal how white nationalism, a kind of nationalism centered on the supposed inferiority of minorities, is seeping into the party.

The Republican party has had members who ascribe to this ideology among its elected officials for a long time. Iowa Congressman Steve King, first elected in 2002, has made a number of controversial statements over the years. He suggested on the House floor in 2006 that the top of a border fence should be electrified to discourage people from fooling around with it because “we do that with livestock all the time,” and in 2008 declared that an Obama victory would result in “al-Qaeda … dancing in the streets in greater numbers than they did on September 11 because they would declare victory in this war on terror.”

As recently as the 2016 Republican National Convention, King asked a panel on MSNBC to go back through history and find an example of “contributions that have been made by these other categories of people.”

King is not alone in making these kinds of statements. In 2016, Maine Gov. Paul LePage said “You shoot at the enemy. You try to identify the enemy. And the enemy right now, the overwhelming majority of people coming in are people of color or people of Hispanic origin.”

But since the election of President Trump, these figures have gone from the fringes of the party to a central part of Republican rhetoric. The president famously began his campaign saying Mexicans are “bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists and some, I assume, are good people.” He took several days to denounce the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, declaring that there were “fine people” on both sides.

This sets a precedent — and in 2018, we saw the effects of such rhetoric.

In Illinois’ 3rd Congressional District, Republican candidate Arthur Jones had a section of his website titled “Holocaust?” that featured documents denying the Holocaust ever even happened.

And Russell Walker, the Republican candidate in a heavily Democratic North Carolina state House district, stated on his website that Jews are satanic and openly believes that “someone or group has to be supreme and that group is the whites of the world.”

Both of these candidates lost their bid for election. But Jones was able to secure almost 27 percent of the vote and Walker was able to secure 37 percent of the vote.

Jones and Walker ran in districts that typically go Democratic and don’t usually run Republican candidates, but this phenomenon is not merely confined to this kind of district. The Republican nominee for U.S. Senate in Virginia, Corey Stewart, referred to his fellow Republicans as “weak” for apologizing too quickly following the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. Rather than denounce the rally as a display of racism, he made several joint appearances with the organizers of the rally. Even though he did not win, he received 41 percent of the vote.

These increasingly racially charged statements were not confined to losers either. Florida’s next governor, Ron DeSantis, invoked racial slurs when he said voters should not “monkey this up” by electing his African-American opponent, Andrew Gillum.

The Republican party cannot stop these candidates from running for office. But there are many things the Republican party and its leaders could be doing to distance themselves from these candidates. The Illinois Republican party said nothing as Jones gathered signatures to run, did not challenge the signatures when he submitted them and didn’t even run any other candidates against him in the primary. The party even failed to organize a write-in campaign for the general election, leaving Republicans in the district with little choice but to support a Holocaust-denier for Congress.

Jones ended up getting more than 56,000 votes. While he was officially denounced by the Illinois Republican Party, it undertook no action to demonstrate to voters that he does not represent Republican, conservative values. In Virginia, Stewart wasn’t even denounced. After his victory in the June primary, Trump pronounced loud support for him.

This does not mean that all members of the Republican party are inherently racist by nature. But the 2018 campaign season has proven that racists, bigots and white nationalists are beginning to see the Republican party as a place for their platform. The Republican party must say one thing loud and clear — racism and bigotry in any form should not be accepted in the Republican party, and candidates like Jones and Stewart do not represent American values.

The GOP must take coherent action to stop candidates like these from using their platform. Until it does, we must continue to vote against it in every election.