Professors examine gun violence, mental health correlation

November 27, 2018

Adam Lanza, James Holmes, Elliot Rodger and Nikolas Cruz have all been considered mentally ill. But unlike most of the 43.8 million adults who live with mental illness in any given year, these four men were in the news for mass murder — brought about by gun violence.

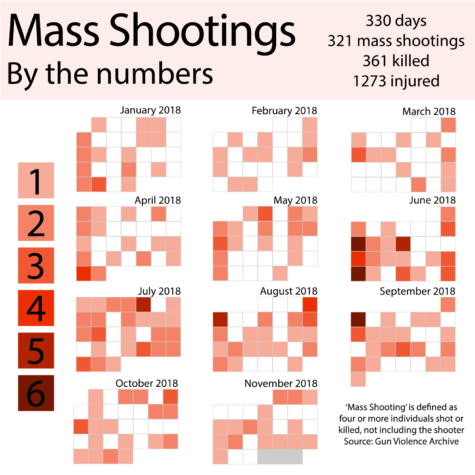

After 346 mass shootings in 2017, 321 have occurred so far in 2018 — and studies continue to show an increasing number of these incidents, most of which are committed by men. When it comes to understanding the individuals who pull the trigger, their intentions are often linked to mental illness by politicians and members of the public, like was the case with the recent mass shooting at a Pittsburgh synagogue which claimed 11 lives.

While that can be the case, some experts believe other conditions play themselves out in the head of the mass shooter that make it difficult to prevent these events from happening.

Daniel Walsh | Staff Illustrator

Daniel Walsh | Staff Illustrator

According to a 2016 study published in the Annals of Epidemiology journal, only four percent of gun violence can be linked solely to mental illness. Edward Mulvey, a psychiatry professor at Pitt, said the American public tends to associate mass shooters with mental illness — but he disagrees.

“I don’t believe the mass shooting phenomenon is driven by mental illness,” Mulvey said. “The idea that there’s some kind of magical thing that if mental health could just take care of [mass shootings] it would go away, is a myth. These people aren’t usually engaged in treatment, they aren’t usually diagnosable.”

Richard Garland, a Pitt assistant professor of public health practice, said prejudice against an individual or a group of people that can stem from different places — including home, school and the internet — is often at the root of violence.

“One of the first things [people] say is [the mass shooter] has to have a mental health problem,” Garland said. “But hate is the thing that drove him to do what he’s done.”

While it can be difficult to diagnose mass shooters by looking through a diagnostic lens, Mulvey said looking retrospectively at certain patterns and behaviors allows professionals to make connections. He said instances of “leakage” — where someone considering violence tells another individual about their violent beliefs or intentions — usually occur before someone commits a mass shooting.

According to Pitt psychology professor Daniel Shaw, a common thought process individuals undergo before deciding to commit mass murders is “depersonalization” of victims. He said depersonalization — the process of allowing oneself to not see someone else as a human being — is what allows a shooter to justify what they are doing.

“You don’t see someone as a person,” Shaw said. “You start using a name, you call them ‘the people,’ things like that. That’s beginning to think of someone as subhuman, when they become an ‘it’ or a thing or a pronoun, it becomes much easier to see that person dead. If you’re socialized to see people as not human … that’s really dangerous.”

Often behind this depersonalization is the shooter’s explicit belief that the victims of these events deserve this kind of violence, Shaw said. Mass shooters believe certain groups or individuals are “somehow beneath” them, which to them justifies their actions and allows for depersonalization.

According to Garland, these thought processes can often be traced back to childhood.

“There’s something that’s been going on at home or in the community that we missed,” Garland said. “People will say when they look at [the mass shooter’s] history that they have been bullied, they have been picked on, shunned by their community … it causes them to snap, but we don’t find out about it until after they’ve done something.”

While it’s helpful to examine behavior leading up to the event, Mulvey said analyzing the behavior of mass shooters isn’t enough to prevent these incidents from occurring. Garland, Shaw and Mulvey all said stronger legislative action is needed to deter mass gun violence.

“The easy solution is to say it’s mental illness and we need more mental health services,” Mulvey said. “But that’s really the politically easy thing to say. If you think about it in terms of actually changing the landscape on how we deal with these problems, that isn’t going to do it.”