Column | Pittsburgh gun bills fail civil rights and safety

Via PittsburghMayorsOffice | Wikimedia Commons

Three bills introduced in December by Erika Strassburger and Corey O’Connor meant to ban assault weapons and accessories contained parts of ineffective and outdated laws.

January 22, 2019

City Council members Erika Strassburger and Corey O’Connor introduced three bills last December that would ban assault weapons and various accessories and seize guns from suicidal or violent individuals.

But the gun control ordinances, crafted by O’Connor and co-authored by Strassburger, were cobbled together by cutting and pasting pieces from ineffective and outdated laws. The results are policies that experts say have serious civil rights implications — without making the City any safer.

What’s in the ordinances?

O’Connor and Strassburger have readily described the proposed ordinances as “common sense” gun laws but entire sections of the ordinances appear laden with details the council members themselves don’t understand.

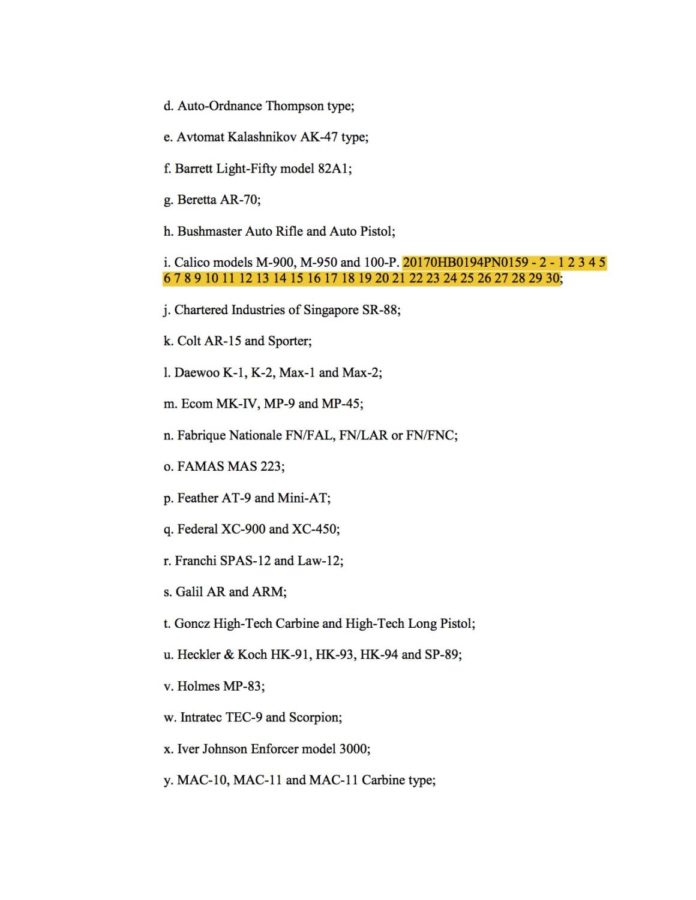

The ordinances would ban assault weapons, defined by firearms function, a features-based criteria and a list of guns banned by name. On item “i” of the list, the guns “Calico models M-900, M-950 and 100-P” are followed by a string of numbers and letters: “20170HB0194PN0159 – 2 – 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30.”

But these numbers and letters aren’t guns. “20170HB0194PN0159” is the bill code on the second page of Pennsylvania House Bill 194, which contains the same list of guns. The rest are the page number and the line numbers. Their inclusion in the ordinance is a remnant of a sloppy copy and paste.

The bill code, page number and line numbers of Pennsylvania House Bill 194 were inadvertently carried over to the proposed Pittsburgh ordinance when copying and pasting the list of banned guns.

The same list of guns followed by the bill code, page number and line numbers is found on the second page of Pennsylvania House Bill 194.

Strassburger was forward about the list’s origins, explaining it was “drawn from House Bill 194.” Copying and pasting isn’t an inherently careless way to write policies — as long as the copied content is analyzed — and it’s common in local government.

“At the local level and at the level of several of the smaller states, where legislators are part-time or have limited resources, [copying and pasting] is a very common practice,” Ben Bratman, professor of legal writing at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, wrote in an email.

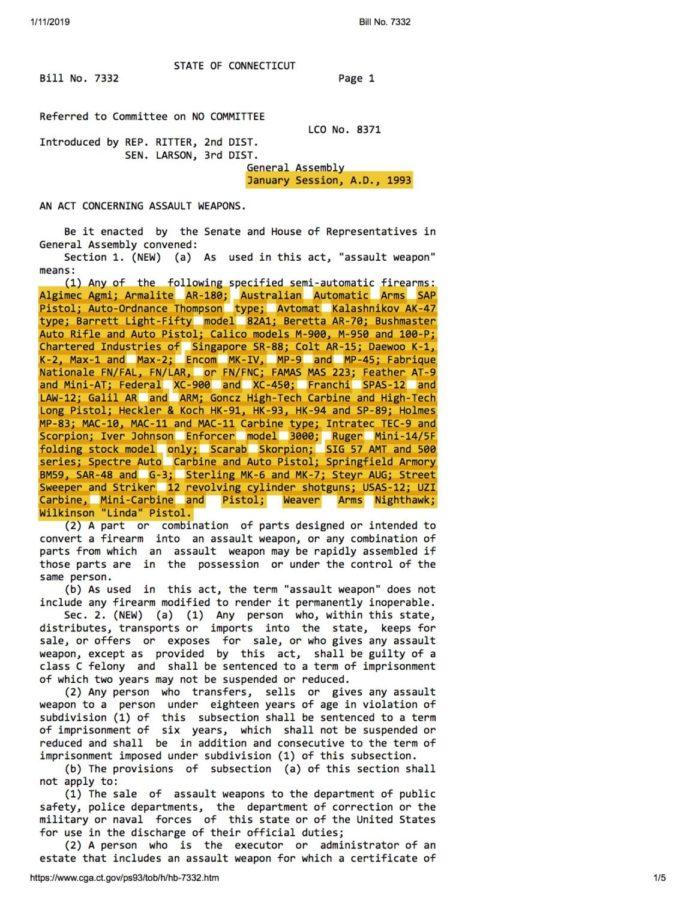

But it seems O’Connor neglected to research the listed guns, which also appear in a Connecticut law introduced in 1993. Despite Strassburger’s claim that the list represents guns with “proliferation and prominence of segments of the firearms market-share,” most of the guns have not been made in years — and in many cases, decades.

Connecticut’s 1993 assault weapon ban contains the same list of guns as the proposed Pittsburgh ordinance.

“Only about 12 or so of the approximately 75 firearms listed by name in the proposed ordinance are still produced in any iteration that I am aware of,” Joshua Rowe, a Pittsburgh gunsmith with two decades of experience in the firearms industry, wrote in an email. “Frankly, this list is so far off the mark that it could easily be a bad-guy prop list from some 1980’s B–list action flick.”

The firearms list is likely not the only section copied from other legislation. The “prohibited accessories and features” portion of the accessories ordinance is word-for-word identical to a California assault weapons ban, banning guns with features like “thumbhole stocks” and “a forward pistol grip.”

The assault weapon criteria in the accessories ordinance differs from that of the assault weapon ordinance that bans guns with a different set of features like “bayonet mounts” and “threaded barrels.”

When asked why cosmetic features like bayonet mounts qualified guns as assault weapons, Strassburger seemed stumped.

“That’s a really good question, you got me,” Strassburger said. “I don’t have a good answer for that.”

A video interview with O’Connor scheduled for Jan. 18 was canceled the day before. O’Connor’s chief of staff and legislative director both declined to give phone interviews.

What will the ordinances do?

The proposed ordinances are ostensibly aimed at making Pittsburgh safer from gun violence. But experts see the policies as ineffective, unenforceable and prone to civil rights violations.

The features-based criteria of the assault weapon ordinance is identical to that of the 1994-2004 nationwide federal assault weapons ban, and a 2004 Justice Department-funded study on the federal ban found no clear evidence it saved lives.

“Should it be renewed,” the report concluded, “the ban’s effects on gun violence are likely to be small at best and perhaps too small for reliable measurement.”

Any effect the ordinance may have on mass shootings is just as dubious. In a 2016 study, Dr. Benjamin Blau of Utah State University analyzed almost 200 mass shootings over a 30-year period and examined both federal and state assault weapon bans.

“Unfortunately, we were unable to identify any particular law that meaningfully lowered the probability of these events,” Dr. Blau wrote in an email. “With regard to assault weapon bans, we didn’t even find that these bans deterred the use of assault weapons during the mass shooting.”

Not only do research studies cast doubt on the ordinances’ effect on gun violence, the proposed measures are almost unenforceable, according to Nicholas Johnson, a professor of law at Fordham University’s law school and a nationally recognized expert on gun policy.

“Nothing would prevent a resident from purchasing outside Pittsburgh and bringing the gun in to Pittsburgh,” Johnson wrote in an email. “If it’s a private sale, there is no real chance of enforcement.”

Inconsistent enforcement of gun laws has serious civil rights and racial justice implications. In 2016, 51.3 percent of individuals convicted of federal gun crimes were black, a racial disparity larger than any other federal crime — including drug crimes. Similar disparities in sentencing because of the proposed ordinances would likely also occur.

In an op-ed to the Los Angeles Times, Adam Winkler, professor of constitutional law at the UCLA School of Law, argued that magazine bans are more likely “to be enforced primarily against racial and ethnic minorities, who are disproportionately the target of police investigations, searches and suspicion.”

“We would have every reason to anticipate that there will be racially disparate enforcement of these new ordinances,” said Clark Neily, vice president for criminal justice at the libertarian Cato Institute.

What’s next?

In a letter to O’Connor dated Jan. 9, Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen Zappala made his opposition to the ordinances clear.

“I believe that City Council does not have the authority to pass such legislation,” Zappala wrote, concluding that “the legislation currently before the Council, if passed, will be found unconstitutional.”

Zappala also voiced his concerns over arrests from the ordinances.

“Once you start arresting people, there are constitutional implications to that, there are civil rights implications,” Zappala said to CBS Pittsburgh.

Despite the letter, O’Connor has not changed his intent to pass the ordinances.

“He has every right to his own opinion, we are still going to move forward,” O’Connor said to CBS Pittsburgh. “Whatever happens after that we will find out.”

O’Connor likely doesn’t have to wait to find out what will happen. The Pennsylvania preemption law that prohibits local municipalities from passing their own gun laws has been upheld in court multiple times and legal experts agree Pittsburgh lacks the authority to pass the ordinances.

“The ordinance would violate the Pennsylvania preemption statute,” Johnson wrote. “Philadelphia mayors pushed similar laws over the years mainly to make a political point. Lynne Abraham, the District Attorney at the time, refused to waste time on enforcement noting that the Philadelphia [assault weapons ban] was a plain violation of state law.”

What it means for Pittsburgh

Many City leaders supporting these measures have a candid interest in finding the best solutions to gun violence. Strassburger herself has consistently been receptive to criticism of the ordinances. But the crude blunders made when crafting the ordinances may leave residents questioning the integrity behind this latest push for gun control.

Between his call for gun control in early November and his introduction of the bills in December, O’Connor had more than a month to craft his ordinances. A bogus description of the content within the ordinances and the oversight in allowing a remnant of a sloppy cut and paste make its way into proposed legislation all cast doubt on the level of sincere effort O’Connor is willing to invest in preventing gun violence in his own City.

The carelessness displayed by City leaders in cobbling together a remedy to gun violence is more than just a failure to proofread their work. It’s a failed commitment to Pittsburgh.

Jeremy primarily writes on law enforcement issues and violent crime (and tacos) for The Pitt News. Write to Jeremy at [email protected].