Faculty braces for Pitt’s union “stalling tactics”

When Ann Cudd arrived at Pitt in August to become provost, new faculty asked her at an orientation session whether she and the rest of the Pitt administration supported a faculty union, which organizers are trying to form right now.

“Faculty members own this institution, and they are the people who govern it,” Cudd said. “[But] I’m not really clear what the need would be.”

And in 2017, at a University Senate meeting, Chancellor Patrick Gallagher was equally lukewarm about a faculty union.

“My guess is that a fair analysis would show pros and cons,” he said. “Again, there’s probably things we could be doing better and they might feel they get more leverage through a union than without. But I think sometimes unions don’t always represent everyone equally well … Also, there are union dues and other things that cost the faculty for that representation.”

But despite these comments from the top, many organizers said they know better than to think administrators have their best interests at heart. Tyler McAndrew, a prominent organizer and visiting lecturer in the English department, said he and others in the union effort are gearing up for a battle in the coming months. And up to this point, the process has been hard work.

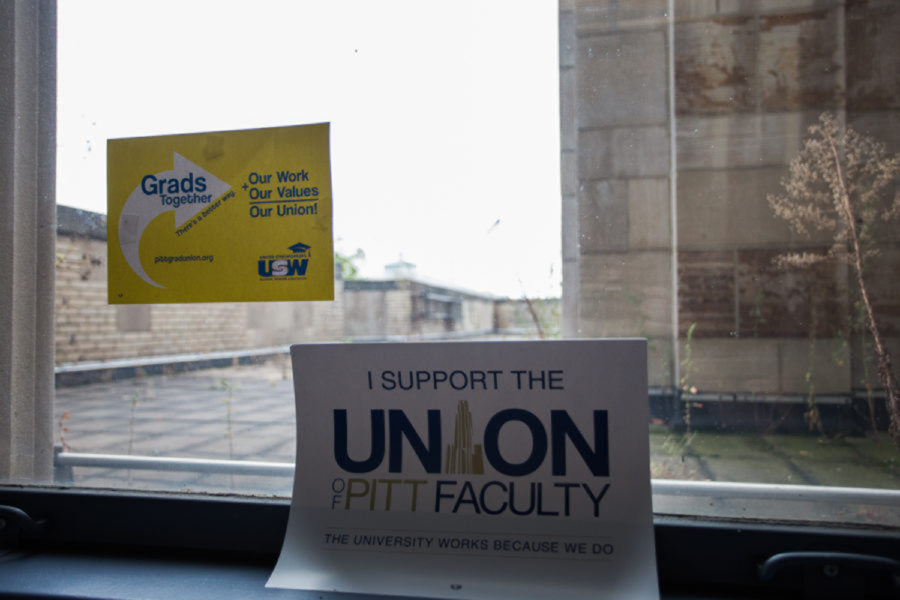

Unionization efforts were well underway by the time Cudd delivered her speech. After several years of on-the-ground campaigning, organizers began collecting signed authorization cards from more than 3,500 Pitt faculty in January 2018, citing many pay- and job-security-related concerns. They filed for an election with the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board, or PLRB, exactly one year later with more than the requisite 30% of faculty needed to prompt an election.

The University responded swiftly, hiring Ballard Spahr, a Philadelphia-based law firm that offers “union avoidance training,” according to its website. In a teleconference with union leaders and United Steelworkers representatives in March, Pitt administrators demanded two major alterations to organizers’ proposed bargaining unit: include the medical school and its 3,600 employees, effectively doubling the size of the union, and exclude chairs, whom the University claimed held “supervisory positions” similar to those of administrators.

“These are stalling tactics, pure and simple,” McAndrew said. “The medical school is a separate bargaining unit … and it’s been that way for decades. This proposal doesn’t make any sense.”

The PLRB ruled in 1976 that the School of Medicine was a separate bargaining unit due to its different funding and employment structure, a decision the board reaffirmed in 1990. For one, McAndrew said, many medical school faculty are jointly employed by Pitt and UPMC, whereas conventional Pitt faculty are employed solely by the University.

The medical school also receives close to three-quarters of its funding from grants and various other outside sources like the National Institutes of Health, not the University, according to Guillermo Romero, who teaches biochemistry in the medical school. That fact alone, he said, defeats the medical school’s interest in a union, because faculty could only bargain with the University for a fraction of their incomes.

And that’s partly why, Romero said, the medical school’s bargaining unit, the Faculty Association of the School of Medicine, or FASM, has remained dormant since its inception — the same year Pitt faculty tried and failed to unionize for the first time.

“I can tell you just by talking to my peers … the medical school doesn’t want a union,” Romero said.

A number of other university faculty unions, like Temple University’s TAUP, which represents 13 of the university’s 15 schools, also exclude the medical school. TAUP vice president Jennie Shanker said she would fully support a union of medical school faculty, but that they’ve never expressed any interest.

“Medical schools aren’t exactly cash-strapped,” Shanker said. “I think some professions are just more corporate and can rake in cash more easily … They just don’t have much of an interest in collective bargaining.”

But Cudd said the faculty union should encompass all Pitt faculty, and leaving out the medical school because of an outdated ruling defeats the campaign’s purpose.

“The idea that [the medical school] would be excluded from the bargaining unit seemed inconsistent with the overall goal of the unionization effort, which is to represent all of the faculty,” Cudd told the University Times in March.

USW researcher and organizer Robin Sowards said if the medical school wanted an active union, it could start campaigning within the one it currently has. Logistically, he said, decertifying FASM, which the University petitioned to do last month, and joining the two bargaining units adds needless complication to the entire process — but he thinks that’s part of the University’s plan.

“This kind of move — packing the [bargaining] unit — is so standard that it happens in at least half of all organizing campaigns in all sectors,” Sowards said.

Sowards cited Yale’s graduate student unionization campaign as one of the most consequential examples. Yale’s graduate employees petitioned for separate bargaining units in several different departments in 2017, which would allow grad students to opt out of the union, but the University demanded each department be combined into one large unit. Organizers then pulled the petition, suspecting they’d receive an unfavorable ruling from the Trump-appointed chair and general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board, thereby setting a poor precedent for grad unions nationwide.

Read: Pitt faculty see future in union

According to the NLRB, many employers threaten legal delays to dampen morale, drum up legal costs and ultimately defeat unionization efforts.

“[Pitt’s administration’s] purpose in raising objections appears to be to deprive the faculty of their right to a prompt election by introducing months of needless litigation,” Sowards said.

But Pitt’s decision to exclude supervisors, namely chairs, from the union rests on better legal precedent than trying to include medical school faculty, Sowards said.

McAndrew maintains that chairs are faculty, and exist to advocate for their departments despite performing some administrative tasks.

“The chair is a rotating position … It alternates every two to three years,” McAndrew said. “And at least in the English department, the chair is elected by faculty.”

It works the same way in other departments, according to Pitt statistics chair Satish Iyengar. Iyengar assumed his position at the beginning of this year, and said he’ll serve as chair next year before taking a sabbatical the following year. He declined to say whether he signed a union authorization card, and admitted he’s not sure which way he’ll vote once the PLRB determines an election date. But he said regardless of the decision, he tries his utmost to advocate for faculty in his department.

“First and foremost my duty is to my department,” Iyengar said. “I’m a professor because I like teaching and research, and I want to make those things easier for other faculty in my department, who I’m sure have the same goals.”

Just like many other chairs, Iyengar’s administrative tasks include recruiting part-time faculty, assigning work to faculty, defending candidates for tenure against upper management and monitoring the department’s finances.

For these reasons, Pitt believes chairs should be classified as administration, according to University spokesman Joe Miksch.

“Faculty members who fill these important roles should be classified as management,” Miksch said in an email. “[But] having managerial duties and being classified as management is a legal determination and has nothing to do with whether chairs are advocates for faculty.”

Iyengar remains unsure if chairs should be labeled as administrators, but said he can see arguments on both sides.

“It’s true that I see myself as a professor in most contexts,” Iyengar said. “But it’s also a fact that I perform administrative tasks … It’s a tough decision without an easy answer.”

Incoming English chair Gayle Rogers declined to say whether he supported the unionization effort or believed chairs should be included in the main bargaining unit. He said the entire point of the union vote was to ensure chairs don’t speak for faculty in their departments.

“As an entity itself, the English department, like any department or unit of the University, is neither pro- nor anti-union,” Rogers said in an email. “Many of our colleagues helped launch the unionization effort, but no individual or collection of individuals speaks for ‘the department,’ myself included … The nature of holding a vote itself is that everyone wants individual faculty to decide for themselves.”

Still, the question of whether chairs represent faculty or the administration has been hotly contested in several faculty union contracts, especially in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education, which has a single union to represent all 14 of its member schools, not including state-related universities like Pitt, Penn State and Temple, incorporates chairs within its bargaining unit.

By contrast, the TAUP fought the university over that very issue, with legal assistance from the American Federation of Teachers, and had their chairs removed from the union. Shanker, who was on the front lines of that battle, said losing chairs has created more of an adversarial relationship between chairs and faculty.

“It’s like they’re stuck in limbo,” Shanker said. “Most chairs’ natural instinct, because most of them have their roots as faculty, is to stick up for the faculty in their department … But now, they worry about advocating for things like faculty pay raises, which is unfortunate and it’s a barrier to our progress [in the union].”

To some extent, it’s arbitrary which faculty unions get to keep their chairs, Sowards said. Some colleges grant chairs more administrative power than others, and some are given career-long appointments.

“Since [Pitt’s] department chairs often rotate in and out, and are often elected by their colleagues, we believe that they remain fundamentally faculty members, not supervisors,” Sowards said.

During a hearing with the PLRB, which is currently scheduled for multiple days in July beginning on July 10, Sowards said USW organizers and attorneys plan to debate the NLRB’s criteria for determining supervisory status. That includes a 1990 PLRB decision that determined all faculty who serve on the University Senate, a shared body of governance between faculty and administrators, were supervisors. For the medical school issue, organizers will supply witnesses and documents to highlight the stark differences between the medical school and the main faculty unit.

Read: Pitt faculty file for union election

In the meantime, while organizers prepare for the hearing, McAndrew said they’ll probably have to fend off anti-union propaganda from the University in the coming months.

“It hasn’t happened much yet, but looking at a lot of other union campaigns, I think we’re gonna see a lot of messaging calling the union a third party that swoops in and takes away agency from faculty,” McAndrew said.

But McAndrew emphasized repeatedly that the union will be made up entirely of faculty, who will all have a say in the decision-making process. Shanker said prior to Temple’s adjuncts voting for entrance to TAUP in 2015, the university sent out emails and fliers telling professors a union could make their lives more difficult.

“Not so,” she said with a laugh. “I think adjuncts at Temple are on cloud nine compared to where they were five years ago … The contract we negotiated a couple years ago gave part-time faculty more than a 30% raise.”

Shanker said her three years as an organizer could be grueling at times, but seeing the impact of her and other organizers’ work has made it worthwhile. McAndrew hopes the same will be true of his time at Pitt.

“It’s messy to deal with … but at the end of the day, this is nothing we weren’t expecting and I’m optimistic we’ll get through it,” McAndrew said. “I hope this time next year, I can talk to you as a proud member of Pitt’s faculty union.”

Neena is a senior staff writer at The Pitt News who has covered Pitt's graduate student and faculty union campaigns since January 2019. Originally from...