Opinion | A leftist push won’t help Democrats

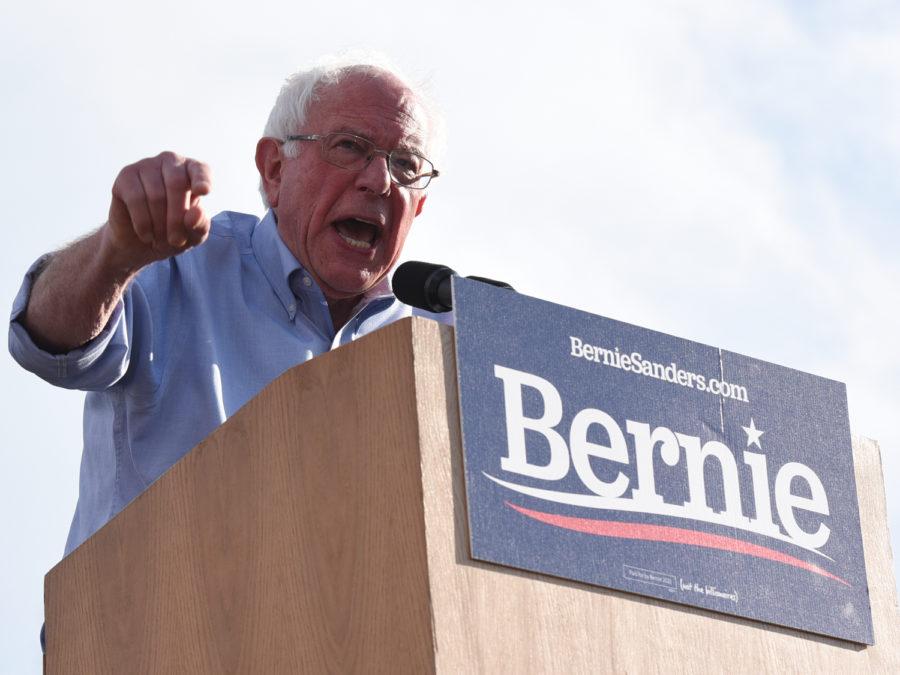

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) during a presidential campaign rally on Pitt’s campus on April 15.

June 25, 2019

The first of a dozen debates among candidates for the Democratic Party’s 2020 presidential nomination will take place tonight in Miami. Coming just eight days after President Donald Trump announced his own re-election campaign at the Amway Center in Orlando, Florida, this marks the true beginning of primary season, as well as an opportunity for voters to see which candidates can survive on a national stage. More to the point, it will be a competition to find out which, if any, of these 20 candidates are fit to replace Trump.

The shock that resonated across the nation, both among supporters and opponents, at the startling upset of Hillary Clinton in the last presidential election has not yet worn off. Owing to that, the party as a whole — voters, intellectuals and most importantly, candidates — are as focused on unseating the president in 2020 as they are to any of the other, highly specific goals in the party’s platform, which include universal health care, nationwide gun control and a radical environmental plan as litmus tests rather than a set of general principles by which to abide.

Some polls suggesting high popularity of socialism and many other progressive policies might tempt some to conclude that the party is making a permanent leftward surge. It’s true that surveys show a non-trivial share of Americans supporting many of these ideas, but as the popularity of their leading champion, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), has fallen, there is still room for a moderate to take the nomination and defeat Trump with swing voters, who seem to support moderation as a whole, even if some ideas poll well.

Still, the shift to the left is something to be taken seriously, and a few candidates, including former Maryland Congressman and 2020 hopeful John Delaney, have seen this firsthand. Most recently in the early days of June, Delaney argued that alternatives to the “Medicare for All” single-payer health care policy supported by many Democratic lawmakers are worth considering — a statement met with a torrent of boos from the crowd at the California Democratic Convention. Former Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper, another recent entrant to the race, received similar treatment for his remark that “socialism is not the answer.”

It merits asking whether former Vice President Joe Biden, as of now the lead candidate, will evade the same type of criticism of his history as a moderate, even as he has changed his views in one day on multiple occasions to win over voters. His push for climate action, unsurprisingly, mirrored that taken during the Obama administration — being mostly, and somewhat vaguely, based on incentives for private industry to increase clean energy usage.

His plan now, though, appears to be only a less intense version of the Green New Deal, a far-left plan to cut U.S. CO2 emissions to net-zero by 2030, which Robinson Meyer in The Atlantic noted was formed, sometimes to the word, around demands by activists. Whether Biden’s about-faces will prove popular is something only time will tell, but it is not effective policy. Looking to radical solutions as a first resort runs the risk of failing to achieve meaningful change at all.

The dogmatic acceptance of leftist rhetoric, if not substance, into the party’s messaging might risk alienating moderates and giving the upper hand to the GOP — no stranger to internal battles itself. Republican victories to take the House by storm in 2010 were largely driven by the ultra-conservative Tea Party, a faction which received as much opposition from moderates as Democratic centrists today. That charge, led by groups such as Justice Democrats, seeks to shift the party’s ideological makeup to the left.

Bernie Sanders disagrees that this philosophy is not popular. He instead believes “socialism” is an insult from Republicans looking to discredit his agenda, which, he says, achieves “political and economic freedom in every community,” among other things, making it immensely more palatable than it would be on its own.

Unfortunately, banal statements like this often confuse people with little understanding of the proposals and leave the issue muddied. A survey last year noting strong support for the ideas in the Green New Deal, for instance, found that 82% of voters had heard “nothing at all” about the plan.

This labeling attracts even the ire of those further down the left end of the spectrum, with Democratic Socialists of America clarifying that they do oppose capitalism and do not see a role for it at all in an ideal society.

“If we use the standard definition, democratic socialists don’t support capitalism: They want workers to control the means of production. In social democracies, by contrast, the economy continues to operate ‘on terms that are set by the capitalist class … Our ultimate goal really is for working people to run our society and run our workplaces and our economies.’”

There is no proposal among progressives in general for abolishing private property rights and moving to a planned economy (a relief to many), but critics even fear that a political environment that is too hostile to business would be a move too far away even from the Nordic model that many progressives support, which combines private enterprise and markets with a welfare state and is, in some respects, more market-friendly than America.

While it is certain that tonight’s debate will find much common ground between viewpoints, the traditional, constitutional role of the federal government as a protector, rather than a provider, of rights is one that will come under increasing scrutiny, with Bernie Sanders’ recent proposal for an “Economic Bill of Rights” causing strong reactions on both sides. These criticisms engender visceral images of the 1930s — some invoking the 1936 Soviet Constitution and those who, like Sanders, believe his vision only picks up where FDR left off 80 years ago with the New Deal.

Nevertheless, these debates will also allow each of these candidates to showcase their views on where the United States as a nation should orient itself, ideologically speaking, as some believe this model of a welfare state combined with mostly free markets (which is, to belabor the point, a hallmark of Nordic political economy) is insufficient. Candidates will suggest a range of solutions, from “progressive capitalism” that brings business under tighter supervision, to a newly-minted smorgasbord of state guarantees without consideration of financial costs.

Whichever way one feels about these issues — not least of which is the Trump presidency — the experience of the Tea Party, which rode to the forefront of politics for a very short time, only to be replaced by Trump, is a cautionary tale: unwavering radicalism, warranted or not, breeds populism. The Tea Party’s demands for small government, cuts to federal spending and debt and preservation of traditional values never materialized. Failing to recognize that and instead building a platform on platitudes and “this time is different” optimism will spell a similar death for the far left. The DNC would be wise to reject them.