Old News: When Pitt and ROTC clashed on anti-gay policy

Old News is a bi-weekly blog dragging up ancient Pitt history. Here, we’ll retell some of the weird, interesting or relevant stories we find in The Pitt News’s archives at Documenting Pitt.

More stories from Emily Wolfe

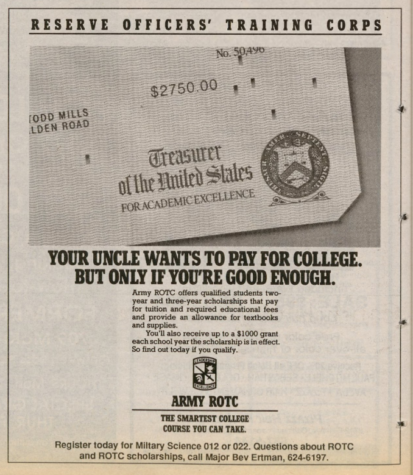

There’s an ad that popped up a lot in the 1990 pages of The Pitt News.

“YOUR UNCLE WANTS TO PAY FOR COLLEGE,” it said in bold capital letters. “BUT ONLY IF YOU’RE GOOD ENOUGH.”

Above the message was a picture of a $2,750 check from the United States Treasury and four words — Reserve Officers’ Training Corps.

In the spring of 1990, 44 students at Pitt were here on full scholarships from the Department of Defense. The deal appealed to many, like it still does today. ROTC covered books, fees and tuition for the selected students — on the high end, about an $8,000 value each year — in exchange for a few years of military service as a commissioned officer after graduation.

But like his ad insinuated, Uncle Sam only wanted a certain type of cadet. In order to enroll in third- and fourth-year ROTC programming and hold on to scholarship benefits, each ROTC scholarship student had to sign a statement indicating they weren’t gay or lesbian. Students who were later discovered to be gay would face not only dismissal from the military, but might end up footing the bill for their college education after all.

This was four years before the introduction of “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” the Clinton-era policy that lasted until 2011, when President Barack Obama signed an act making sexual orientation-based discrimination illegal in the military. Pitt ROTC officers admitted freely at the time that if they found out an ROTC student at Pitt was gay, the student would be kicked out of the program.

“I’m obligated to disenroll them,” Michael Cassetori, an ROTC military professor, said. “I don’t have a choice.”

Universities across the country had already started to look askance at the ROTC policy by 1988, when Pitt added “sexual orientation” as a protected category in its nondiscrimination statement. When Pitt administrators were asked about the contradiction between the new University stance and the ROTC anti-gay regulation, though, they got cagey.

Wesley Posvar, then the University’s president, said in 1990 Pitt didn’t have jurisdiction over ROTC because it was an “outside” program and Pitt’s nondiscrimination statement only applied to faculty, staff and students. Although ROTC instructors at Pitt were listed as professors of military science, Posvar said that was an honorary title.

Posvar didn’t like ROTC’s discriminatory policy, but he wanted to take a national approach to the issue. Ending the ROTC program at Pitt would just hurt the students enrolled in it, he said.

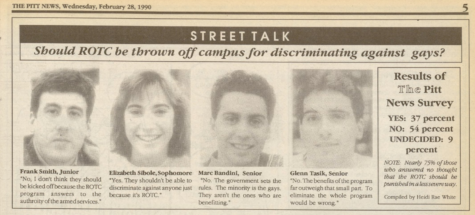

Everyone on campus seemed ready to take a position on the issue. BiGALA, the lesbian, gay and bisexual student organization, advocated for ROTC to be pushed out of Pitt if it didn’t start allowing lesbian and gay cadets. The College Republicans said they agreed with Posvar that scrapping the ROTC program wasn’t the solution. Individual students wrote in on both sides.

It was around this time that the ROTC’s recruitment ads, maybe unsurprisingly, disappeared from the paper for a while.

On April 16, near the end of the semester, the issue made its way to a University Senate Council meeting, where some members of the Senate disputed Posvar’s claim that ROTC policies were outside of Pitt’s control. Several faculty members voiced discomfort with the fact that ROTC students received Pitt credit for high-level ROTC-specific classes — courses which, though technically open to non-ROTC students, were in practice essentially limited to students who had signed the statement affirming they were heterosexual.

In the last development in the narrative before the close of the school year, the Senate voted to create a committee of faculty and students to explore the question. When school picked up again with no mention of ROTC breaking Pitt rules, it seemed like the issue might have disappeared for good.

Pitt moved on. It was August of 1990, and ROTC started recruiting in the pages of The Pitt News again. People argued about new things in the opinions section, like whether or not it would be OK for Pitt to start charging for basketball tickets. The Gulf War started and ended. Pitt announced that John Dennis O’Connor would replace Posvar, who was retiring from his role as president.

Then, on May 22, 1991, the Senate council’s committee returned its result. ROTC was a University program and had to follow University rules, it said. The members of the committee recommended that O’Connor phase out the program by 1997 if the Department of Defense refused to change its policy. The Senate Council voted in June to endorse the recommendation.

Give me some time to think about it, O’Connor said.

Eight months later, he announced that he was rejecting the suggestion to get rid of ROTC. O’Connor would take other action advised by the committee, including acknowledging that ROTC was a University program and that its anti-gay discrimination conflicted with University policy, but he argued getting rid of the program entirely would “harm a segment of our community” without any real result.

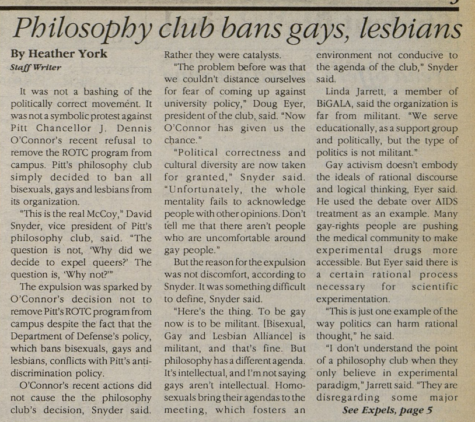

While SGB issued a statement expressing its disapproval of O’Connor’s choice, some students took a different tack. Doug Eyer and David Snyder, the president and vice president of Pitt’s philosophy club, put their heads together and decided in early March to ban all bisexuals, gay men and lesbians from their organization.

“The problem before was that we couldn’t distance ourselves [from homosexuality] for fear of coming up against University policy,” Eyer said. “Now O’Connor has given us that chance.”

But when Snyder moved later that month to institute the same ban at Pitt’s pre-law society, of which he was president, he was more straightforward about the point he was making.

“All we’re trying to do is get the administration to confront the issue,” he told the members of his club at a meeting. “When you have a society that is not doing it symbolically, the administration is forced to face the issue.”

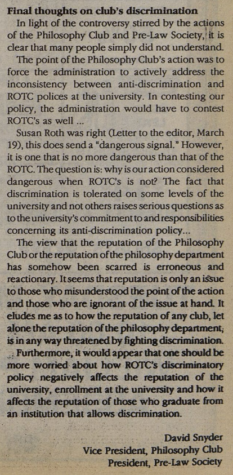

The rest of the pre-law society rejected Snyder’s proposal instantly, and Eyer wrote in a letter to The Pitt News that the philosophy club did not plan to follow through on its proposed ban. Snyder, disappointed that his plan had not had the effect he wanted, wrote in as well to explain his reasoning.

“Why is our action considered dangerous when ROTC’s is not?” he said. “The fact that discrimination is tolerated on some levels of the university and not others raises serious questions as to the university’s commitment to and responsibilities concerning the university’s anti-discrimination policy …”

Eyer and Snyder’s scheme was the last great effort to get Pitt’s administration to take action on the ROTC conflict — at least during this episode, and at least according to the archives of The Pitt News.

At the end of 1992, though, speculation was high that President-elect Bill Clinton planned to get rid of anti-gay discrimination in the military altogether — though that turned out not to be true — and campus groups and students seemed, once again, “to be sharply divided on the issue,” The Pitt News reported.

“This policy is mean-spirited and will [one day] be long forgotten,” Mark Smith, a graduate student, told the paper at the time. “In the meantime, it will cause more campus unrest and civil disobedience.”

Most of the information in this story was originally reported by Scot Ross, Jennifer Calabrese, Jenna Ferrara and other writers at The Pitt News in the early 1990s.

Copies of the The Pitt News from 1910 to 2014 can be viewed at Documenting Pitt in the University Archives.

Emily Wolfe is the digital manager at The Pitt News. An Ashburn, Virginia native, Emily plans to graduate in 2022 with majors in fiction writing, French...