Editorial: Better response needed from state health officials in Canon-McMillan school district

October 8, 2019

Rather than assuage the concerns of members of the Canon-McMillan School District in Washington County, a community meeting on Monday stirred up anger and concern instead.

The meeting was about an abnormally high rate of rare cancer diagnoses in children in the area and concerns that environmental factors could be contributing to this phenomenon. However, the meeting did not provide any answers for concerned parents and suggested that the problem was not as bad as it actually is. It seems as though state health officials haven’t appropriately or adequately responded to community members’ complaints, who have cause to be worried about their children’s health.

Southwestern Pennsylvania is home to abnormally high numbers of rare childhood cancers. In the Canon-McMillan School District, there have been six cases of the rare childhood bone cancer, Ewing sarcoma, diagnosed in the past 10 years. Two of these cases were diagnosed just last year. Only 250 cases of Ewing sarcoma are diagnosed each year in the United States, so this is a concerning concentration of cases for one school district.

However, during Monday’s community meeting, state Department of Health officials and an expert on Ewing sarcoma from UPMC shared their analysis of why there isn’t a Ewing sarcoma cluster in the Canon-McMillan School District. A cancer cluster is a higher than expected number of cancer cases contained in one geographical area over a short period of time.

Based on the six cases of rare cancer found in this small area, it seems as if this situation would qualify as a cancer cluster. But the Health Department used only three of the six cases to come to the conclusion that while there was a higher number of female students than normal in the area with Ewing sarcoma, there wasn’t a cluster.

Community members weren’t happy with this conclusion. They also weren’t happy about the fact that the panel — consisting of a wide array of health officials who have researched Ewing sarcoma — couldn’t answer most questions posed to them. The officials couldn’t respond in particular to concerns that exposure from shale gas could be the cause of such a high number of cases of Ewing sarcoma in the area in the past decade, especially given that shale gas operations started in the region in 2005.

Sara Rankin, of the Southwestern Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project, said neither her organization nor the Health Department could say whether or not environmental factors are contributing to this problem.

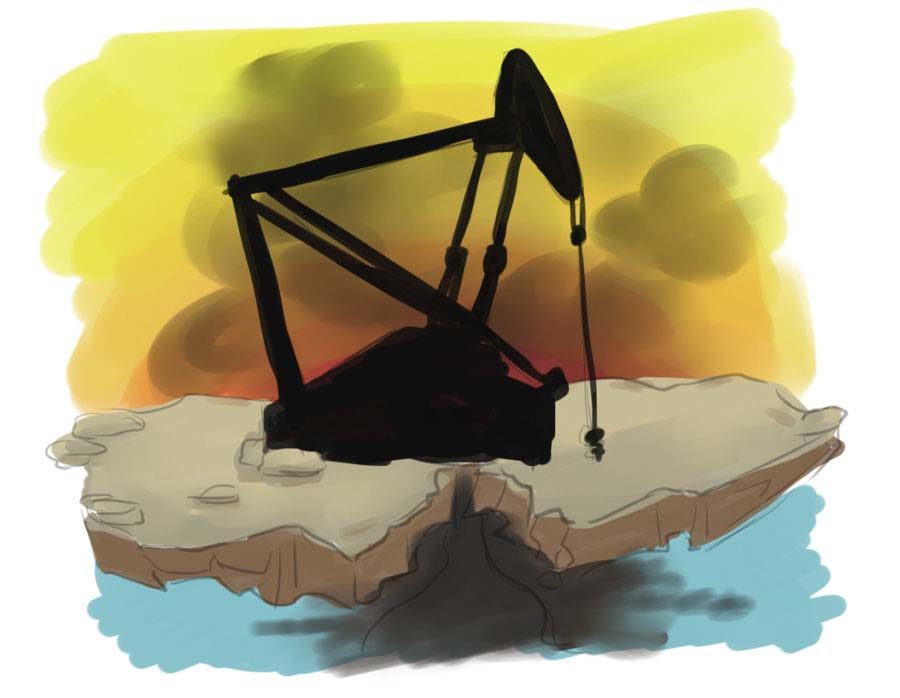

“What we do know is that southwest Pennsylvania has been inundated by shale gas development, an industry that emits 55 compounds which are either known, probable or possible carcinogens into our environment,” Rankin said.

Dr. Ned Keyter, a retired physician and member of Physicians for Social Responsibility Philadelphia, claimed that there was more than enough evidence for the state to take action against this public health crisis.

“It is now clear that more than enough scientific medical information exists for Gov. Wolf and Health Secretary Levine to take precautionary measures protecting public health by calling for a halt on shale gas extraction in Pennsylvania until a thorough, unbiased and transparent investigation is completed on the high rates of rare childhood cancers, including Ewing sarcoma,” he said.

Because there is so much concern and such strong suggestion that these cases might be linked to shale gas extraction, the public meeting was insultingly uninformative for parents concerned for their children’s health. The state needs to take a closer look at fracking, and it needs to do so immediately.