Column: State-by-state pay-to-play bills are only a start

October 9, 2019

The world of college sports has seemingly changed forever following the passing of a California bill in late September that will allow student athletes their first chance at getting paid.

The Fair Pay To Play Act, or measure SB 206, was passed by a unanimous 72-0 vote in the California State Senate on Sept. 9 and signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom on Lebron James’ show “The Shop,” later finalized on Sept. 27. The law, which will go into effect by Jan. 1, 2023, will allow college athletes in the state to profit off their own likeness, which could involve athletes signing endorsement deals with companies, starring in commercials or even starting their own camps.

Eleven other states have already put forth their own bills to allow players to be compensated for their image, including Pennsylvania, Florida and Illinois. And while this is a great start toward progress, this state-by-state approach could lead to discrepancies in athlete pay and recruiting disadvantages within those states that don’t catch up in time.

That’s why the next step forward is for the bill to be introduced and passed at the national level.

Republican Anthony Gonzalez, an Ohio congressman and former Ohio State football player, is trying to introduce a national bill that would allow athletes across the country to profit off their own likeness, instead of having each individual state try to pass bills of their own. The current approach means that all 50 states must make bills that pass and then put them into effect by the time that California has its bill, or else risk facing a major disadvantage for getting recruits who could make a profit elsewhere.

This approach would also mean that each bill could differ depending on the state, resulting in varying degrees of how much money athletes can make off endorsements and jersey sales. This would again lead to recruiting discrepancies — for example, Brooklyn Sen. Kevin Parker wants to distribute 15% of ticket sales among all student athletes at the end of each year. A national bill would curb these problems by putting all states on a level playing field, eliminating any blatant advantages for recruits within one state.

If a comprehensive bill were introduced in Congress, it would likely pass, considering the generally unifying nature of the issue at hand.

On the left side of the political spectrum, civil rights activists and Democratic politicians are in general agreement that these athletes should get paid for their work because of the amount of money they bring into the universities. On the right, conservatives and those in favor of the free market agree that these athletes shouldn’t be prohibited from profiting off themselves.

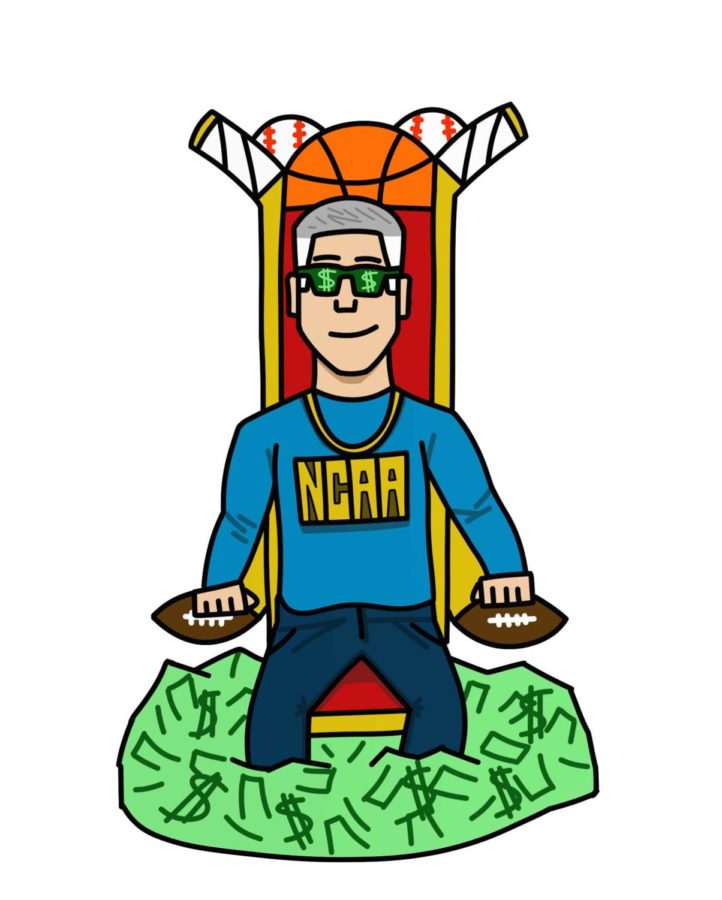

The NCAA and universities, of course, have every incentive to ensure that bills like this do not get passed. It’s in their best interest to make as much money as they can by declaring students “amateurs” and granting them nothing for their hard work and dedication besides a scholarship often disproportionate to the revenue they generate. And if a student is a walk-on or competes in Division III, they are not on athletic scholarship at all.

The NCAA and Pac-12, a Power 5 conference, quickly spoke out against California’s bill. NCAA president Mark Emmert argued that it will change athletes into professionals.

“This is just a new form of professionalism and a different way of converting students into employees,” he said.

Article 12 of the NCAA Division I Manual discusses amateurism and contains rules that the student athletes must follow. Within Article 12 is Bylaw 12.5.1.3, “Continuation of Modeling and Other Nonathletically Related Promotional Activities After Enrollment.” This bylaw prohibits college athletes from making money off of the fact that they play a sport at their university.

Meanwhile, regular college students are allowed to profit from private interests. If a college student wants to write a book or start their own company, they can make money off of those enterprises without being kicked off campus or expelled. Under that same manual mentioned, it states that college athletes are, in fact, students.

Student athletes have previously faced discipline or ineligibility for breaking this rule. In 2017 alone, the NCAA threatened the eligibility of Texas A&M runner Ryan Trahan for creating his own water bottle company, and UCF kicker Donald De La Haye was prohibited from making money off of his own YouTube videos.

The NCAA has already warned California that its schools could face heavy fines and possible expulsion. They argue that the law will allow the state to have a tangible recruiting advantage over others and that it’s unfair to states that won’t have this bill in place yet — all the more reason to pass it at the national level.

The passage of a nationwide bill could also be extremely beneficial for female collegiate athletes. Women in professional sports don’t get paid at all what the top men do in their respective sports. On “The Shop,” Diana Taurasi, a dominant basketball player at UConn from 2000-2004, said the university is still profiting from her championships. Former UCLA gymnast Katelyn Ohashi, whose floor routine went viral on YouTube last year and garnered more than 65 million views, also appeared on the show and said she didn’t make a dime from the viral routine.

If we want student athletes to be truly compensated for their work, it can’t just stop at a scholarship or meal plans. It must allow these athletes to make money off of themselves, build their brand in college and then use that to progress into a professional career in sports or in another field they choose. It can also help them pay for many things they couldn’t before, like providing financial support for their families back home.

The window for collegiate athletes to profit off of their image is a small one. If there is to be proper compensation for the work that these athletes do, then simply letting them make money from that image should be allowed — but on a national level.