Part 2 | A look at the back-and-forth between Pitt, faculty union organizers

Organizers accused Pitt of inflating the bargaining unit to derail unionization efforts. Pitt representatives called it a misunderstanding.

University of Pittsburgh faculty unionizers at the People’s Pride parade in June 2018.

This article is the second part of an in-depth series about Pitt’s faculty union campaign. Read from the beginning here.

After matching signed authorization cards to faculty names from Pitt’s eligibility list, the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board ruled in April that union organizers had failed to collect enough cards from eligible faculty to prompt a union election. Union organizers swiftly responded with claims that the University tried to derail unionization efforts by submitting an inflated list of union-eligible faculty.

“We haven’t seen the list yet, but we’re pretty sure Pitt packed the [bargaining] unit with all kinds of people who shouldn’t be in there — students, retired faculty, administrators,” union organizer Caroline Brickman said in an April interview just days after the PLRB ruling. “I think the administration’s scared. They’re scared to be honest with us.”

According to a study by the American Federation of Labor, many employers threaten legal delays to dampen morale, drum up legal costs and ultimately defeat unionization efforts. An “inflated” union eligibility list dilutes the significance of each authorization card, making it harder for union organizers to collect cards from the 30% of faculty needed to prompt a union election.

So when organizers received the eligibility list in June, they said they were appalled, but not surprised, to find several dozen administrators who clearly don’t belong in the bargaining unit.

Pitt denies organizers’ allegations that it “packed” the bargaining unit

According to university spokesman Kevin Zwick, Pitt wanted to exclude administrators from the very beginning of negotiations, and it was organizers who were lukewarm toward the idea. Pitt even presented United Steelworkers’ legal team with a list of faculty positions that Ballard Spahr, the University’s “union avoidance” law firm, had advised it to exclude, but Zwick said USW never agreed to erase any class of administrators from the bargaining unit.

“The University did not have agreement from [organizers] on who should be excluded as a manager or supervisor,” Zwick said. “The University’s list had to include faculty categories that we identified as involving managers and supervisors, because the USW’s petition includes those on faculty appointments.”

Most of the negotiations about the size of the bargaining unit took place in a March 1 teleconference call between USW, union organizers at Pitt and the University’s lawyers.

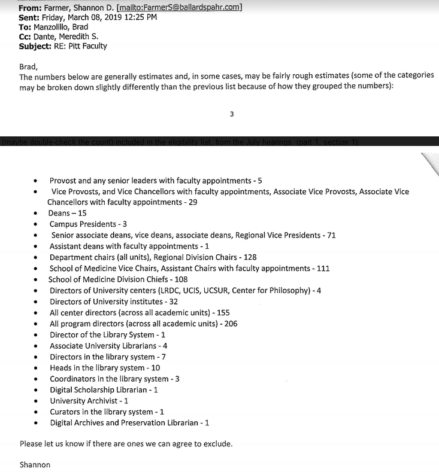

The Pitt News obtained a private email exchange between USW organizer Brad Manzolillo and Ballard Spahr attorney Shannon Farmer dated March 8 — a week after the call and a couple weeks before Pitt submitted its list of eligible faculty to the PLRB. In her email to Manzolillo, Farmer proposed a list of nearly 900 exclusions broken down by position, not by name.

Farmer said in her email that Pitt wanted to exclude the chancellor, all provosts and vice provosts, all deans, associate deans and assistant deans and directors of “centers,” “programs” and “institutes” from the list of eligible faculty. But all classes of administrators in Farmer’s email were eventually included on the eligibility list, except the chancellor, provost, a few other senior officers and the 219 administrators from Pitt’s medical school.

Pitt and organizers have debated whether or not to include the medical school in a faculty union, but no one from the medical school was included in the March showing of interest list submitted to the PLRB.

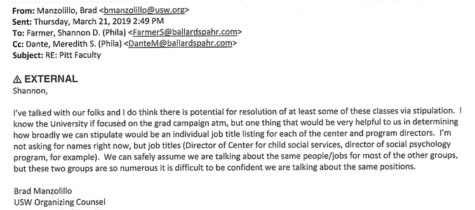

Manzolillo’s response to the email — “I’ve talked with our folks [at USW] and I do think there is potential for resolution of at least some of these classes” — did not list out specific classes of administrators to exclude from the bargaining unit.

Zwick said that email exchange corroborates Pitt’s side of events — organizers never said which administrators they wanted to exclude from the bargaining unit, so the University went ahead and included almost everyone. No Pitt spokesperson took part in the March 1 conference call.

Organizers double-down on allegations that Pitt intentionally inflated the eligibility list

Robin Sowards, a USW researcher and organizer who was on the March 1 call with the University’s lawyers, said the idea that Pitt’s attorneys were ever confused about whether to include assistant deans, associate deans and vice provosts in the unit is “pure fantasy.”

A 1990 PLRB ruling determined that about 300 “managers” at Pitt — all deans, provosts, chancellors, presidents and a few other top officials — were ineligible for a faculty union when Pitt faculty tried and failed to unionize that same year.

“We made clear in our conference call that we were petitioning for the unit described in the PLRB’s 1990 decision, which excluded the various deans, presidents, provosts and chancellors since they are all supervisory and/or managerial,” Sowards said.

Sowards also claimed that, during the call, Ballard Spahr promised to give organizers the list it was putting together for the PLRB, so that both parties could reach an agreement about who should be in the unit, rendering the hearings completely unnecessary. On the call, Farmer agreed with organizers that the unit only contained about 3,500 faculty, Sowards said, but she and the University’s other lawyers subsequently included hundreds more individuals.

Farmer could not be reached to confirm or deny Sowards’ statements — she was out of office for an unspecified period, as of last Monday. Zwick said Farmer “won’t be available for this story.”

The Pitt News cannot confirm what was said during the call — both sides declined to provide meeting minutes or phone transcripts. But The Pitt News has conducted interviews with more than half a dozen organizers since January, when organizers filed for an election. And during those interviews, no organizer ever said they supported putting administrators in the faculty union’s bargaining unit.

“As for who’s eligible [for the faculty union] … definitely all adjunct, full-time and tenured faculty,” organizer Tyler McAndrew said in January. “Maybe department chairs … after that I’m not sure.”

“We definitely want chairs [in the unit],” Brickman said in April. “Anyone above that works for administration … and the administration clearly doesn’t have our best interests at heart.”

Sowards claimed that if organizers hadn’t been clear about wanting to exclude assistant and associate deans and vice provosts from the bargaining unit it shouldn’t even need to be said.

“No faculty union in human existence includes those people,” Sowards said. “It’s like arguing that office furniture should be included in the bargaining unit.”

Pennsylvania is home to 14 public schools under Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education, four state-related schools (including Pitt, Temple and Penn State) and 14 community colleges, all under the jurisdiction of the PLRB. PASSHE has a single faculty union to represent all 14 of its members schools, and Temple added adjuncts to its faculty union in 2015.

The Pitt News researched union contracts from PASSHE and Temple, the only four-year universities under the jurisdiction of the PLRB that have faculty unions, and found that neither one included assistant deans, associate deans or vice provosts within its bargaining unit.

The highest-ranking faculty members in any Pennsylvania faculty union were department chairs. PASSHE’s union incorporates chairs within its bargaining unit, whereas Temple, a state-related school like Pitt — which receives some government funding but isn’t entirely public — does not include chairs in its faculty union. Temple’s administration used Ballard Spahr, the same “union avoidance” law firm assisting Pitt, to pull department chairs from its bargaining unit in 2015.

Pitt organizers and administration are still debating whether to include chairs in its bargaining unit, as the role combines normal faculty duties and supervising other faculty. Organizer Tyler Bickford said organizers want chairs in the unit because they’re “an ally to faculty,” but he also said “that’ll probably be a tough battle to win.”

Union eligibility for some faculty still up in the air

After months of negotiations, hearings and subpoenas, Sowards said there are still questions about whether certain groups listed in Farmer’s email should be in the bargaining unit, because organizers aren’t completely sure who fits those criteria.

Farmer wrote in her email that there are more than 400 directors for “centers,” “programs” and “institutes,” all of which Pitt wanted to exclude from the list. The Pitt website lists about 200 centers and institutes, but it’s unclear how Ballard Spahr determined that there were more than 200 program directors. The University doesn’t have a centralized list of programs, and by counting manually, organizers said they come up with 100 program directors at most.

Even then, many program directors, like Bickford, the director of graduate studies in the English department, maintain that they’re regular faculty who don’t hold managerial positions.

“I’m not anyone’s boss,” Bickford said. “I work collaboratively with other people in the department to discuss which kinds of classes might be in the curriculum or who might teach a class, but I have no authority to tell a faculty member, ‘you’re not teaching classes next year’ … All of our work ultimately gets approved by chairs or deans.”

The difference between Bickford’s job and Holger Hoock’s job as associate dean of graduate studies is that Hoock actually negotiates salaries and controls employment contracts for faculty and graduate students, whereas Bickford just proposes certain types of programming in the English department.

But the title “director” can mean a lot of different things, Bickford added. There’s no systematic or legally standardized definition of the position. Some directors, like Bickford, don’t supervise any faculty, but the director of the library system is a dean-level position.

That’s where this all gets fuzzy, Sowards said, and it’s also why Manzolillo asked for a list of “centers,” “directors,” and “programs” that correspond to the number of “directors” Farmer lists in her email, because organizers aren’t sure which directors qualify as supervisors.

“Ballard Spahr has still not provided us with that information even though we are plainly entitled to it,” Sowards said. “The idea that the University is asking for clarification from us is absolutely absurd … it’s in our interest to reach an [agreement]. It’s in their interest to stall the election.”

Zwick said the University is still compiling the information, since Pitt “does not maintain [the] information centrally.” He did not specify when Pitt would supply documents to organizers.

Read the next and final part of this series here now. The rest of the series is here:

Introduction

Part 1

Neena is a senior staff writer at The Pitt News who has covered Pitt's graduate student and faculty union campaigns since January 2019. Originally from...