Old News: Happy Franksgiving

Old News is a bi-weekly blog dragging up ancient Pitt history. Here, we’ll retell some of the weird, interesting or relevant stories we find in The Pitt News’s archives at Documenting Pitt.

More stories from Emily Wolfe

It was one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s less popular ideas to reinvigorate the American economy — with an extra week of Christmas shopping.

Back in 1939, holiday shopping before Thanksgiving wasn’t just taboo, it was unheard-of. So when retailers noticed that Thanksgiving fell on Nov. 30 that year — leaving America with a shortened Christmas season — people panicked. But Roosevelt found a solution. In August 1939, he announced that American Thanksgiving would actually be officially celebrated on Nov. 23, the third Thursday of the month, and not the last, as was traditional.

Instantly, there was an uproar. Roosevelt’s “Franksgiving” was breaking with more than 75 years of tradition — when Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863, he had said the country would “set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.”

There were logistical concerns too. When Roosevelt made his announcement at the end of the summer, college football teams had already set their schedules for the coming season, which were often planned around Thanksgiving.

Notably, the states that objected most strongly to the proposition tended to be led by Republican governors who might have political reasons to push back against Roosevelt, a Democrat. A number of states, including Pennsylvania — led by Republican Gov. Arthur James — simply declined to go along with the president’s date-change.

And in 1940, after Roosevelt announced that the third-Thursday Thanksgiving date would continue, Pennsylvania was the only state out of all 48 to once again hold on to the later date. While students across the country returned home from college to join their families for Thanksgiving, Pitt’s holiday break came a week later.

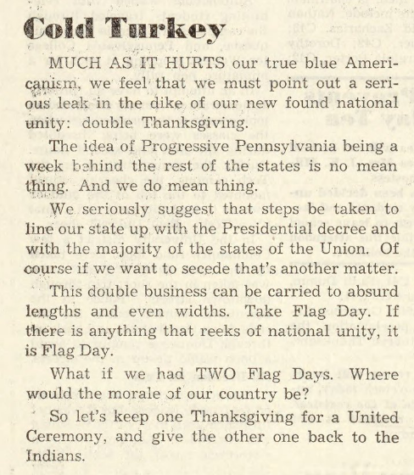

The Pitt News’ editorial board came down firmly against the two Thanksgivings in a 1940 editorial called “Cold Turkey.”

“The idea of Progressive Pennsylvania being a week behind the rest of the states is no mean thing,” TPN wrote. “We seriously suggest that steps be taken to line our state up with the Presidential decree and with the majority of the states of the Union.”

How far, the editorial asked, could this madness be extended? To “absurd lengths and even widths?”

“Take Flag Day. If there is anything that reeks of national unity, it is Flag Day. What if we had TWO Flag Days? Where would the morale of our country be?” it said.

Jerry Jonas, a columnist for the Bucks County Courier-Times, recalled some of the awkwardness caused by the two Thanksgivings in a 2016 piece.

“I was only a youngster at the time, but the years of Pennsylvania’s double Thanksgivings are still vivid in my memory,” Jonas wrote.

Those who worked in Pennsylvania but lived in bordering states had to go to work on national Thanksgiving anyway, Jonas said. And a week later, some Pennsylvanians had to get up on their state’s Thanksgiving and go to work in other states.

The next year, Jonas notes, pushback against the early Thanksgiving had once again grown, and Pennsylvania wasn’t alone in celebrating at the end of the month. Congress, at last, pushed through a bill to kill “Franksgiving” for good — bringing the holiday back to the last Thursday of the week — though it wouldn’t take effect until November of 1942.

So in 1941, Pennsylvanians and Pitt students had to deal, once again, with the awkwardness of the two Thanksgivings.

“Both Thanksgivings are over so it’s back to work on the college campuses,” wrote one weary Pitt News editor at the end of November.

Emily Wolfe is the digital manager at The Pitt News. An Ashburn, Virginia native, Emily plans to graduate in 2022 with majors in fiction writing, French...