Pittsburgh painter captures reactions to “Lest We Forget”

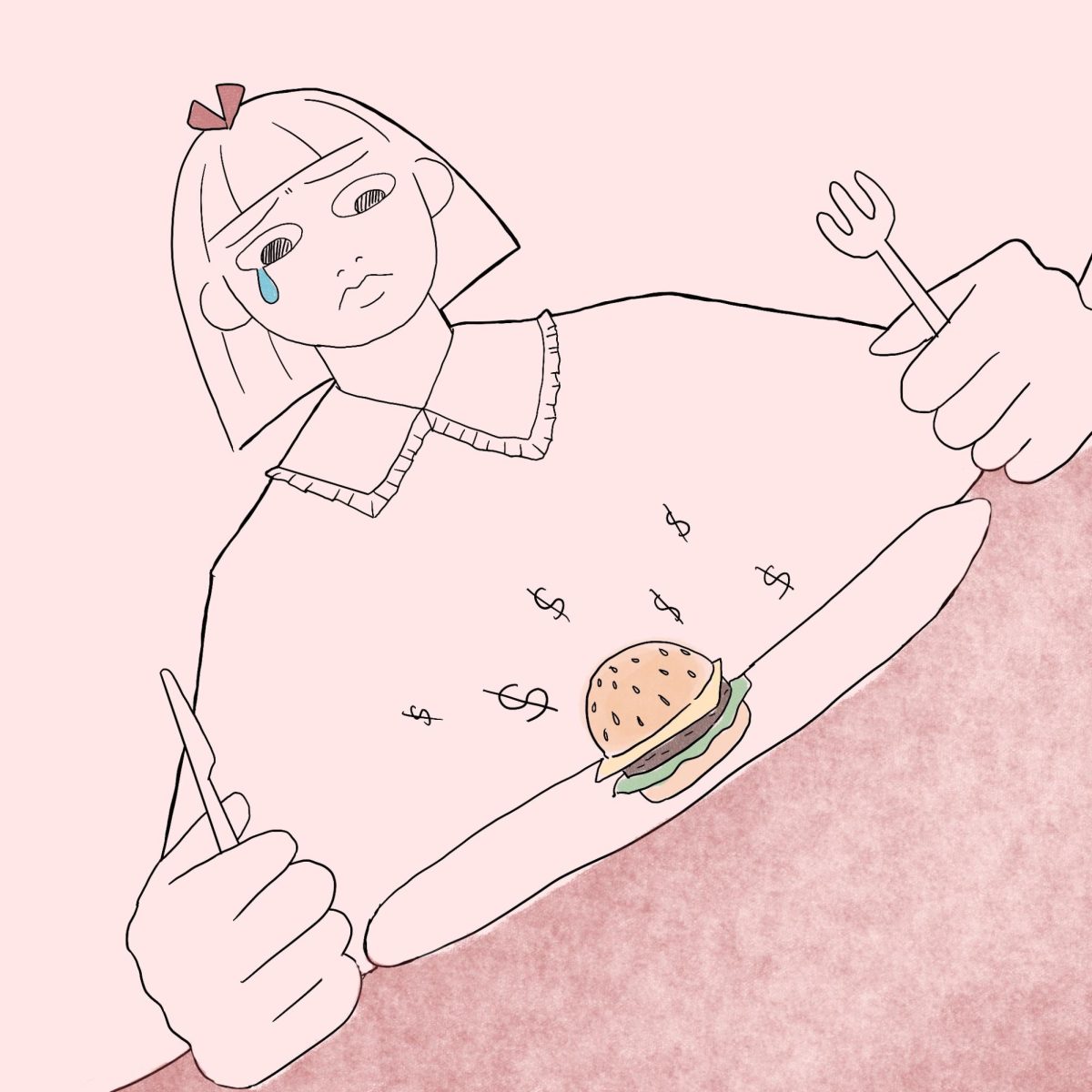

Adam Maeroff’s painting “Cloudy with a Chance of Learning” shows a visitor to the “Lest We Forget” exhibition that was on display on the Cathedral of Learning lawn last fall.

January 7, 2020

Emily Loeb noticed a man taking photographs as she and two companions walked through the “Lest We Forget” exhibition on the Cathedral of Learning lawn last fall, but she didn’t think much of it. She figured he, like her, was focused on the series of large-scale photographs that made up the exhibition — 60 portraits of Holocaust survivors taken by German-Italian artist Luigi Toscano, each more than seven feet tall.

“I’ve never seen anything like these gigantic photographs,” Loeb, the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor, said. “You could see every hair and wrinkle and pore on their faces.”

Loeb didn’t know her fellow visitor was watching her reaction to the exhibition, or that her experience, like that of many others who visited “Lest We Forget,” would later be captured in a painting by the man taking pictures — local artist Adam Maeroff.

In fact, “Lady in the Flower Dress,” which shows Loeb and two other women gazing at Toscano’s portraits, is one of about 15 “Lest We Forget”-inspired paintings Maeroff created during the month the exhibition stayed in Pittsburgh.

Courtesy of Adam Maeroff

Courtesy of Adam Maeroff

In the swirling style of Maeroff’s paintings, the faces of exhibit’s visitors are left mostly featureless, but the large portraits of the survivors are still easily identifiable.

“I get out and experience life, see the final painting in my head, then paint it. The personal experience and my perspective of the world is the painting,” Maeroff wrote in an email. “The desired result is a painting which allows you, the viewer, to see through my eyes.”

Maeroff paints a variety of subjects — he’s partial to nature scenes — but he said he’s been drawn to capturing the way people interact with their surroundings since he first started painting in New York City in the ’70s. He visited Toscano’s exhibition on one of his walks around Pittsburgh, and when he started watching other visitors, “all [his] creative bells and whistles were going off simultaneously,” he said.

“Folks engaged the portraits as they moved through them,” Maeroff said. “It was all but five seconds before my mind started seeing paintings portraying what I saw.”

The exhibition, which has been displayed in similar public locations in a number of cities in Europe and America, stood on the Cathedral lawn from mid-October to mid-November. Its appearance was intended to coincide with the one-year commemoration of the Tree of Life masacre, and Toscano photographed a number of Pittsburgh-area Holocaust survivors for inclusion in the exhibit.

During his trips to the exhibition, Maeroff would take pictures or sketch visitors, letting them know what he was doing if he thought there was a chance they would notice. Then he’d return to his home studio, where he’d paint from the references he’d taken. As he completed his paintings, Maeroff posted them to Facebook, where they caught the eye of Toscano himself. Toscano shared the paintings with his followers, saying Maeroff’s works — inspired by his own — left him “speechless.”

“It’s really cool and generous of him to see what I was doing, portraying people responding to his work, as nothing more than what it was — not threatening, just more art,” Maeroff said.

Maeroff and Toscano have since struck up a friendship, and one of Maeroff’s pieces — “Cloudy with a Chance of Learning,” which shows a young woman sitting on a bench, gazing across the walkway at portraits of two Pittsburgh-area survivors — will soon be printed in a book of Toscano’s “Lest We Forget” portraits.

Emily Loeb recognized herself in Adam Maeroff’s painting “Lady in the Flower Dress.”

The original copy of the painting, though, will stay in the City on the office wall of Lauren Bairnsfather, the director of the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh. Bairnsfather, who worked closely with Toscano to bring “Lest We Forget” to Pittsburgh, said Maeroff’s paintings perfectly illustrate why the exhibition is meaningful. “Cloudy with a Chance of Learning” was the first painting of Maeroff’s that Bairnsfather saw. The instant that she did, Bairnsfather said, she knew she had to buy it.

“I loved all of the paintings that Adam did, but that one especially, because it captured exactly the meaning and significance of the exhibit to me,” Bairnsfather said. “It was meant for people to be able to stop as they were walking across the lawn and really take in the images, and that’s what this painting is.”

Maeroff’s series of “Lest We Forget” paintings isn’t so different from the work he’s done in the past, he said. In almost 50 years of art and travel, he’s painted many “strong and struggling faces” — from teenage Midwestern sex workers in the 1970s to starving families in the former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.

Courtesy of Adam Maeroff

“I see you” Courtesy of Adam Maeroff

“In many ways, the faces of the people portrayed in ‘Lest We Forget’ remind me of those people and others who have been characters in the chapters of my life,” Maeroff said.

The difference, Maeroff said, is that he doesn’t know what happened to those faces that he saw and painted in the past. Toscano’s subjects survived into old age.

“The people in Luigi’s portraits survived, and that makes them different to me, a narrative in itself,” Maeroff said.

Loeb was initially startled to recognize herself in “Lady in a Flower Dress” when it showed up on her Facebook feed, shared by Bairnsfather. But when she was sure the painting showed her, she contacted Maeroff and bought the painting — she plans to hang it on the wall of her own office.

“You go through the world and you don’t know who’s recording or painting these moments,” Loeb said. “Maybe we’re all captured somewhere, and we don’t realize it.”