Editorial: It’s too late to fix the Women’s March

The Womens’ March has faced criticism for relying too heavily on female genitalia to demand equality.

January 12, 2020

People packed Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., for the first annual Women’s March in January 2017. Women drove overnight and packed snacks so they could stand all day in demonstration. Now, the nation is approaching the fourth annual march on Saturday, Jan. 18. But this year, people aren’t so eager to travel and paint signs.

The Women’s March — which was founded in response to President Donald Trump’s inauguration in Jan. 2017 — has been roiled by numerous accusations of anti-Semitism, racism and only speaking for white cisgender women. It’s too late to apologize, or to fix its mistakes with a statement. The movement needs to include and speak for people who aren’t white and who aren’t cisgender — in order to do so, the Women’s March must rebranded.

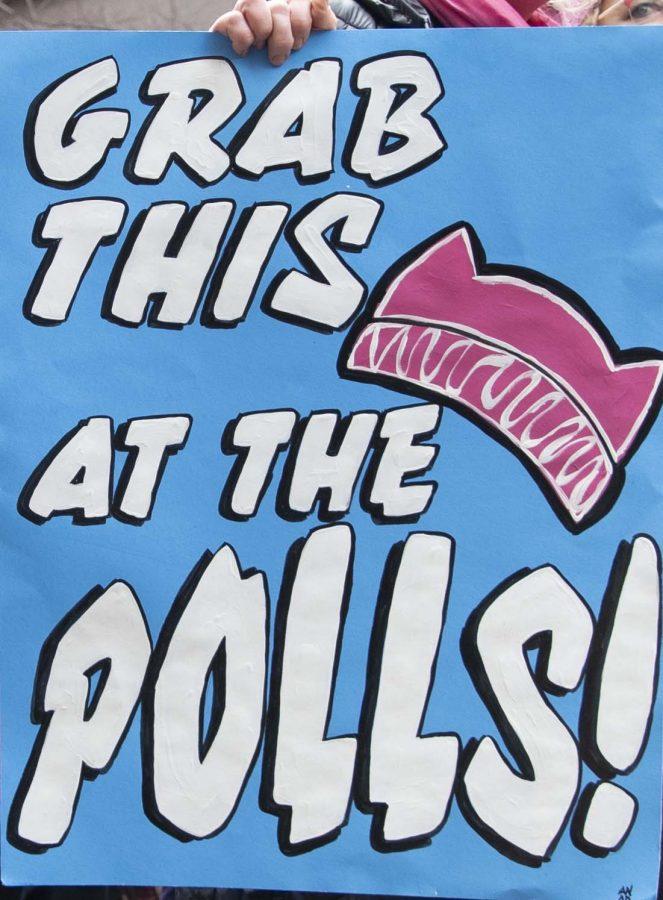

Even by its sheer name, the Women’s March carries discrimination and ignorance. A fundamental staple of the Women’s March is the pink hat with points on the left and the right. It’s called the Pussyhat, and it’s supposed to resemble a vagina. The hats have become a staple of strength. Organizers say things like “pussy grabs back,” and women hold red signs about their periods. But not everyone who experinces female-like discrimination identifies as female. And not everyone who identifies as female has a vagina or menstruates at all — take for example trans women.

“Trans women’s issues are women’s issues: job and housing discrimination, street harassment, substandard health care, domestic violence, murder,” trans woman activist Evan Greer writes. “While the Women’s March made history, it left behind one of the world’s most marginalized groups of women: transgender women.”

Which is all to say, feminism and the Women’s March shouldn’t be geared towards vaginas. The organizers have attempted to make the movement more inclusive to trans and nonbinary people, but each year, the pussy chants and hats return.

People of color have had similar issues. Pittsburgh had two different rallies in 2017 because black activists felt that the march was denying queer people and people of color their voices. It’s been such a prominent issue within the Women’s March movement that groups — in light of the overwhelming amount of white privilege — actually split from the March itself. One of the most prominent groups is March On — a platform quite similar to the Women’s March in tenet principles — which emphasizes criminal justice reform, economic justice and reproductive freedom. But it also gives a voice to marginalized communities left behind in the Women’s March by working towards fairer elections and representation, including an end to gerrymandering and other political strategies that disproportionately affect communities of color.

“We think about intersectionality in a broader way than it’s normally spoken about,” Vanessa Wruble, a key organizer of March On, said. “It’s expansive in terms of gender identification and sexuality, it’s expansive in terms of ability and the disabled community.”

The Women’s March deserves some credit for trying to address the controversies. It’s added Jewish women to its board after organizers made anti-Semetic remarks. It’s added board members who are LGBTQ+, but it doesn’t erase the problems it’s had over the past few years.

This movement that the Women’s March sparked belongs to all of us, no matter our socioeconomic status, race or gender identity. All of our voices need to be heard loud and clear. For as long as the Women’s March stays the Women’s March, that won’t happen.