Opinion | Pitt should prioritize local history

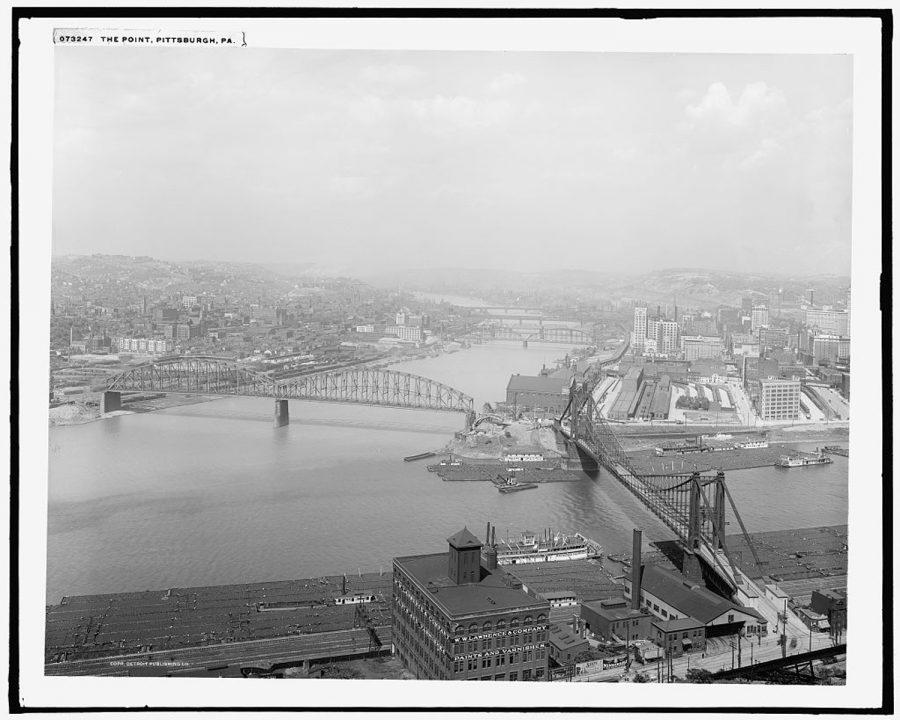

The Point in Pittsburgh during the 1910s.

February 18, 2020

As we make our way through the month of February, the University of Pittsburgh’s signature K. Leroy Irvis Black History Month event approaches. Taking place in the final days of February, the event will feature a commemoration of black activism through the arts.

The University named its annual event in honor of K. Leroy Irvis, former Pennsylvania legislative leader, Pitt Law alumnus and emeritus trustee. A trail-blazing teacher, activist and politician, Irvis dedicated his life to fighting for civil rights and equality. In 1977, he became the first African American to serve as speaker of the house of Pennsylvania House of Representatives.

Understanding Pittsburgh history and local heroes, like Irvis, is an important part of being an active Pittsburgh community member — Pittsburgh is a city rich with diverse arts and achievements. But without knowing the effort and struggles that led to these accomplishments, it is not possible to fully understand just how important they are. By honoring Irvis, the University has made a positive step in promoting local history, but they should implement a required program that integrates a variety of local history topics into all students’ curriculum.

Students need to know about Pittsburgh history in order to fully appreciate our City’s accomplishments. From scientific discoveries like one of the first successful polio vaccines to artistic ingenuity such as the late Crawford Grill, Pittsburgh innovations have changed the world. But we cannot truly understand the historical achievements of our region without knowing the history that led to them. We cannot praise Pittsburgh’s thriving music scene and rich artistic heritage without recognizing the African American abolitionists that started this cultural awakening. We cannot take pride in our region’s role in the labor union movement without acknowledging the immigrant populations that made union strikes possible.

Learning local history is not just about taking pride in the good — it is just as much about acknowledging the bad in order to understand if and how these negative aspects persist today. Mariruth Leftwich, the director of education at the Heinz History Center explains it best.

“The relevance of history is often in the hard history, not the celebratory history,” Leftwich said.

The same African American abolitionists that created Pittsburgh’s artistic culture faced heavy racism and discrimination in the Pittsburgh region. Slavery, lynchings, disenfranchisement and limited access to housing, education and jobs were all unfortunate but very real parts of our City’s history. We must recognize this dark past in order to understand the present-day racism in Pittsburgh.

According to the City of Pittsburgh’s Gender Equity Commission’s City-wide gender and race report, “racial inequality persists across health, income, employment and education in Pittsburgh.” The report views these issues as a result of “individual and structural racism,” but to understand where this racism began, we must know Pittsburgh’s history of bigotry and discrimination.

Learning about local history is clearly an important step in taking pride in Pittsburgh’s achievements and recognizing our City’s shortcomings. But few people are aware of Pittsburgh’s history — especially Pitt students, many of whom come from around the nation and world and may not be familiar with the area, something Leftwich emphasized.

“Pittsburgh is a place that has an identity to it,” Leftwich said. “If you are an outsider, it’s kind of hard to understand and see where that comes from.”

While it is important for students to know local history, we are often very busy, are not equipped to teach ourselves and have no motivation to do so. To bypass these barriers, the University should take charge and integrate local history into students’ curricula.

To be fair, the University has many opportunities for students to learn about local history. There are several classes dedicated to the subject, including Secret Pittsburgh and ReligYinz: Mapping Religious Pittsburgh. The University Library System hosts the Historic Pittsburgh website, which supports personal and scholarly research on local history. Additionally, there are Outside the Classroom Curriculum tasks that have students visit local museums, historical monuments and educational institutes.

As is, however, none of these opportunities are required — a student could go all four years of their college career without ever having to learn about Pittsburgh history. To implement a program that would require students to learn about local history, the University could simply make a local history class one of the general education requirements, or, perhaps even easier, could make a mandatory category of Outside the Classroom Curriculum center around local history.

OCC is a collection of experiences, programs and events at Pitt. OCC is open to all Pitt students, regardless of major, but OCC is not a requirement to graduate. Certain OCC tasks may encourage students to learn about local history, but there is not a dedicated local history OCC category with incentive to participate.

The Honors College OCC, on the other hand, is required for both the Honors joint degree and Honors distinction. Based on a points system, Honors students receive points when they go to mentor meetings, conduct community-based research and more. The Honors OCC shows that a mandatory system for getting students involved in community events is feasible, so creating a required local history OCC category would be as easy as recreating the Honors OCC.

The University could even create the OCC program in a way that not only educates students about local history, but benefits the local community. Some of the OCC credit options could include tasks like visiting historically important businesses, talking to local historians or attending talks with important figures in Pittsburgh history. In doing so, students would learn, but they would also give back by supporting local business and citizens.

In an interview, Leftwich said that “the opportunity to encourage people to learn about local history, to give them credit to learn about local history, is a motivating factor.” She herself was unfamiliar with the details of OCC, but once the general idea was explained to her, stated that “there should be a local history version of that.”

By strengthening our pride and appreciation of Pittsburgh, local history helps students identify with their City and come to terms with how its past affects its future. As Leftwich emphasized, learning Pittsburgh’s past helps students “find their place in” Pittsburgh’s uniqueness.

Loretta primarily writes about politics for The Pitt News. Write to her at [email protected].