Opinion | Account for mental health struggles when shaping curriculum

April 1, 2020

During this lockdown — which isn’t technically a lockdown though it might as well be because I haven’t left my house in weeks — I’ve been spending a lot of my time writing.

I’m not necessarily writing for writing’s sake, as I often like to do. Instead, I’ve been spending much of my time doing schoolwork. I shouldn’t be complaining, people tell me, because virtual learning can give me purpose in a time when it feels like the rest of my world has been pulled out from underneath me. In some ways, I suppose it does. But it certainly doesn’t feel like it.

I enjoy school. I love academic debate. I love mastering a new skill. I love my professors and my peers. I love so much about the learning environment I live in. But living at home, working in my parents’ basement and attempting to navigate a completely new virtual learning system has not been rewarding.

I’ve never had less motivation in my life. I am appalled by my own lack of ability to find the drive to get my work done. I haven’t been able to get myself in a rhythm and routine of accomplishing all of my school work as normal, and frankly, I shouldn’t be expected to.

It’s natural to feel lethargic or unmotivated while self-isolating. Instead of putting unrealistic pressure on ourselves and those around us, professors, students, peers, parents and other individuals should accommodate for these circumstances when creating syllabi, personal to-do lists and asking for help.

It’s not that we should allow ourselves to simply sit on our couches and mope for the foreseeable future, but when allocating tasks — whether it is for our students, superiors, children or ourselves — we should account for the inevitable fluctuating motivation levels, physical and mental health challenges and other roadblocks to productivity. In short, expect less, assist as much as you can and prioritize flexibility.

According to Finian Buckley, professor of work and organizational psychology at Dublin City University, the causes and effects of social distancing on productivity are multifaceted.

“Being without work, or at least not having our normal rhythm, can lead to feelings of ineffectiveness. The lack of opportunities to use our abilities can dampen moods leading to a general sense of sadness,” Buckley said. “For many, being deprived of their natural physical activity regime, be that sport or gym visits, means unfamiliar lethargy and depressed energy levels which are not positive for well-being.”

For many college students, it’s not that the work itself is lacking, but our “normal rhythm” has most definitely been interrupted. Access to tutors has been complicated, mediums for learning have been completely replaced by screens and classrooms have been swapped for childhood bedrooms.

Not only must students combat an unexpected and cumbersome change in circumstance, but we are facing new challenges presented by a radically different way of living.

According to Agustin Chevez of the Swinburne University of Technology, isolation can increase the risk of depression, stress, lack of motivation and burnout. And the consequences aren’t just mental. The impact of isolation is comparable to the effects of smoking 15 cigarettes a day, statistically increasing stress levels, risk of inflammation and resulting in a decreased life expectancy. Isolation is what we have to do, but it is not easy.

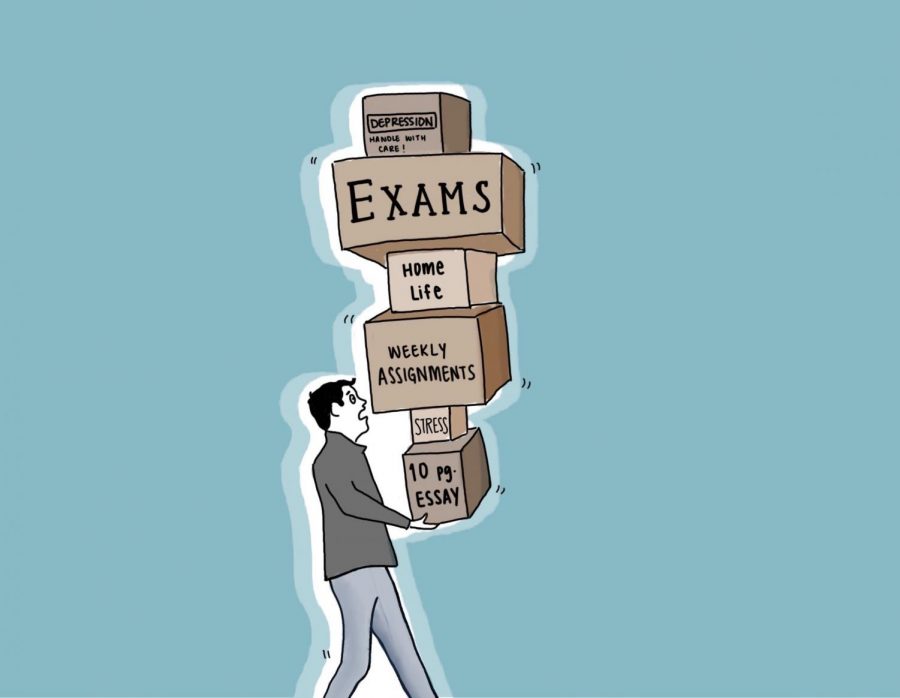

Work loads should account for this pressure. While the University has offered a pass/fail option for students to choose how their final grades will appear on their transcripts, that option does little to assist students in the present. On a weekly basis, I am still being asked to write more than 20 pages, read and respond to close to 200 pages, work two jobs remotely by making calls or writing, take online quizzes, present two group presentations digitally, Zoom for approximately 9.75 hours a week and watch and take notes on an hour’s worth of prerecorded lectures. For a majority of my classes, my workload has increased as a result of this pandemic. If I don’t do any of this, it will be hard to succeed, even in a pass/fail system.

I’m not asking to get credit for course material I have not completed, but I am asking for work allocation to be more collaborative and account for all factors plaguing students’ ability to succeed. Extending deadlines, minimizing busy work and offering once-mandatory assignments as extra credit are simple ways to do this.

This is not the first time schools have had to close in response to an unexpected disaster. For example, schools in New Orleans were completely disrupted and devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. But 15 years later, we have access to new technologies that make a “business as usual” approach seem enticing, regardless of the negative impact on everyone’s mental health.

Being able to hold classes virtually, get materials in the hands — or on the screens — of students instantaneously and working with a generation that is characteristically well-versed in technology would suggest maintaining school practices is a feasible option. However, Zoom doesn’t allow us to gauge a student’s mental state. Just because the option is available doesn’t mean we don’t have to force students to overwhelm themselves.

This pandemic is putting every aspect of our health at risk. Not only are our lungs, hearts and bodies at risk of coming in contact with a deadly virus, but social isolation is putting extreme stress on our mental well-being. It is imperative we shape curricula and expectations with care.

Yes, education must go on, but we must proceed with caution.