Review: ‘Time’ tells love story challenged by mass incarceration

“Time,” an Amazon Prime documentary directed by Garrett Bradley, was released Friday.

October 19, 2020

“Time” feels like director Garrett Bradley’s response to James Baldwin’s “If Beale Street Could Talk.” It is the documented reality Baldwin fictionalized in 1974, with love and nuance and the unflagging fight against incarceration. Bradley holds space for grief and love by accepting what is and pushing against what cannot be accepted.

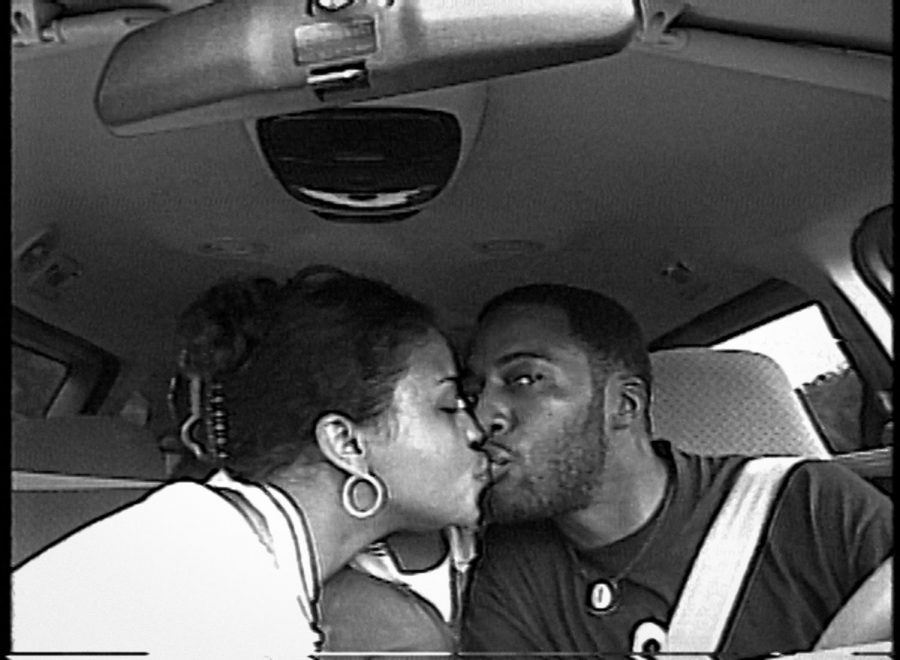

The documentary, released Friday on Amazon Prime, follows Sibil Fox Richardson, a Black abolitionist, wife and mother of six as she fights to get her husband, Rob, released from prison. The film is primarily made up of black-and-white home video footage that Fox shot for Rob while he is in prison. It opens on Fox speaking directly into her camcorder, telling her husband a story, then rousing their kids for the first day of school.

Bradley shoots the rest of the doc in black-and-white to match, and the result is a startlingly intimate film — at times it is difficult to know whether footage is camcorder or professional camera, and this closeness makes the doc feel like a love story.

At its heart, “Time” is not primarily an abolition story, or even a family movie. It is a long and deeply personal love letter from Fox to Rob, shot over 21 years. Fox is deeply certain of her need to bring her husband home.

When she talks about the personal cost of his incarceration, her grief and anger are palpable. She says she “can’t sleep in a bed with him, can’t hold him — and by law he belongs to me — raise my children by myself” and asks who will keep her husband from her. “I can only visit my family when they say I can visit my family. I get to visit my husband two times a month,” Fox says to a group while she is speaking out about carceral injustice.

Fox has a deep and abiding love for her husband and her family, and that love demands justice. This demand for justice leaves no room for defeat or acceptance, and her demands are electrifying. When she speaks to the camera, she speaks with both the energy of a protest leader and the intimacy of a whispered conversation.

Her mother has a similar presence — the first thing she says to the camera is that prison “is almost like slavery time, the white man keeps you there until he figures its time to let you out. This situation is a personal vendetta, it’s a personal vendetta.” That personal vendetta looms in the background of their story, but it isn’t given a voice. There are no lawyers or scenes in a courtroom, and this exclusion is intentional. The verdict of a judge isn’t relevant until that verdict leads to release.

This refusal to sensationalize a courtroom or prison means that Bradley never interviews Rob. We feel his presence in older home video footage, interviews with his sons and mother-in-law and even in the cardboard cutout Fox has of him in her living room. But we do not hear his voice often, and when we do it is filtered through the phone when he calls Fox from prison.

But this absence feels both visually important and respectfully removed. Fox and her children visit twice a month, and the director’s choice not to infringe on or film that time is deference to their family. It is also visually dignifying — Rob is not a prisoner, he is a man in prison, and there will not be any footage of him in a jumpsuit or framed in a plexiglas booth.

It is a contrast to films like “Just Mercy” or “13th,” which are more concerned with the courts and carceral systems at the expense of the personal and intimate grief of their characters and subjects. By centering “Time” on the family members, not the system they are fighting, Bradley makes space for their grief and their love in an intimate way, while acknowledging they are one of many families fighting for justice.

The interviews with the Richardson boys, especially Justus, reveal a deep grief and hope. The home videos of their graduations and school awards are goofy and sincere, showcasing the pride Fox has in her children and the intentionality of their family in the face of separation.

The interspersing of these home videos with footage of Fox speaking at events, calling judges and their secretaries and working at her job is an effective and sympathetic portrait of the constant work she is doing. There is no excess or unnecessary footage. The film is shot with a centeredness and intentionality that doesn’t leave anything out, but doesn’t include anything that doesn’t belong. The result is artistic and arresting, both stylistically and visually. It demands and deserves full attention and does not let that attention waver.

The score complements this full, rich footage with minimal noise and great attention. The score, composed by Edwin Montgomery and Jamieson Shaw, builds low and emotional piano movements that are stylistically similar to those of Nicholas Britell’s in “If Beale Street Could Talk” and Randy Newman’s in “Toy Story” and “Marriage Story.”

Each part of “Time” is individually beautiful and aesthetically arresting, but together the film is a true picture of what a documentary can be. It is a story, told beautifully.