Q&A: Alumni Association award winner Ferdinand Metz on America’s culinary landscape

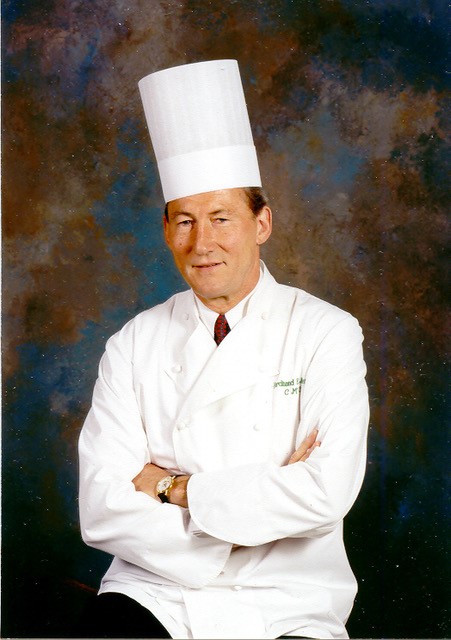

Photo courtesy of Ferdinand Metz

Pitt alumnus Ferdinand Metz currently serves as the president of the Culinary Institute of America.

October 20, 2020

Ferdinand Metz earned a Masters of Business Administration from Pitt in 1975. Now, he holds both an MBA and the title Master Chef — the highest level of certification from the American Culinary Federation.

This homecoming week, the Alumni Association is recognizing Metz for his combination of experience and education. Since graduating from Pitt, Metz has built a career that incorporates his business education with his passion for food.

During his career, Metz has received several awards for his work including a Lifetime Achievement Award from American Academy of Chefs and a gold medal from Master Chefs of France. Metz currently serves as the president of the Culinary Institute of America as well as an International Culinary Judge for the United States. He also authored a book about the Culinary Institute of America titled “The Rebirth of American Cuisine and the Rise of the CIA.”

The Pitt News spoke to Metz to learn more about his education, his career and his views on American cuisine.

TPN: You are being recognized with an Alumni Association award during homecoming week. Can you describe what the award is for?

Metz: Well there are two explanations. One being if you hang around long enough things will happen. The other one is I am on a very unusual career path. To put it in perspective, it was back when I took the first or second MBA that I was enrolled in. At that time when I completed that, I was the only person in America who had a master chef degree and was a certified master chef and had an MBA. That illustrates that my background is unique. It was basically that combination which ultimately led me to accept the position as president of the Culinary Institute of America which, by many accounts, is the foremost culinary school in the world for 21 years.

TPN: In addition to earning your MBA at the University of Pittsburgh, you are also a chef. Why did you decide to pursue this career?

Metz: It was decided for me. When I grew up in Germany my parents had a small hotel, restaurant and butcher shop. My brother and I grew up in that environment and it was almost a foregone conclusion that we would enter the field in one capacity or another. However, my father made it much easier on us. He one day said, “I arranged for you to take an apprenticeship.” Today people will say, “What about career choice? It’s my life,” and all that, but don’t forget at the age of 15 very few people know what they want to be doing. We accepted it very well thinking that my father knew better than we did, which turned out correct.

My brother and I, we wound up taking two apprenticeships, which is unusual because one was a cook, and the other one was a pastry chef — two different things. That also is a combination that very, very few people in our field have. We got a very good, well-rounded education and training. When we went home over the weekend, we saw my parents busy running the hotel and the restaurant and what have you. Before you knew, we basically worked every weekend in addition to the job. We basically had an opportunity — which is so important when you want to learn something — to make mistakes. That gave us tremendous confidence. We had the opportunity to work, and make mistakes and learn at our pace. That’s how we got into the field. Ultimately, I wound up coming to the U.S. and working, at the time, at probably one of the best restaurants in America. I came through Pittsburgh to run the New Product Development division of Heinz. It wasn’t food, but I was able to cover all aspects of the food service industry.

TPN: What training is required to become a certified Master Chef?

Metz: There are only 72 in the whole country. It’s a 10-day examination. Every day you have a theoretical portion in the morning for about three hours. Then, following the three-hour theoretical examination, you have a seven-hour cooking examination. You draw a number out of a hat, and it tells you what you have to do. It covers areas like international cuisine, Asian cuisine, Italian cooking, French cooking, American cuisine — it goes on and on.

At the very last day, you have a mystery basket examination. They give you a basket of ingredients — unbeknownst to you what they might be — and you have to prepare a four-course meal. It was both [mentally and physically demanding] and still is very demanding mentally. You have to be sharp. You have to be focused. And also physically … imagine 10 hours a day under high pressure for 10 days. That’s very demanding.

TPN: You have taken part in several international culinary competitions. What are they like?

Metz: I kept and managed the U.S. Culinary Olympic team for 20 years. We went all over the world — Japan, China, the Netherlands, Greece, Italy. You name it, we were there. All of these are individual country regional competitions. Then, you go to the international culinary event. We were very successful. We won the hot food world championship three Olympics in a row, which was never done before.

But what was much more important was the fact that the learning experience was just incredible. You measure yourself against the best in the world, and in the process — if you keep your eyes and ears open — you learn an awful lot. That was the real experience that meant something.

TPN: Your culinary book “The Rebirth of American Cuisine and the Rise of the CIA” sounds very interesting. Can you describe what the book is about?

Metz: It’s a historic memoir. Historic in the sense that I go back and talk about turning the tables. That’s one of the first chapters where we talk about the extension of American cuisine on a global stage through the competitions. It talks about the judgement in Paris where some of the Napa Valley wines beat the best that France had to offer in a blind testing, which was a watershed moment for the wine industry. It talks about us doing the bicentennial dinner for the Queen of England. It sets the stage to say, “Hey, America has turned around.” We are no longer viewed as the nation of hot dogs and hamburgers.

TPN: Did you uncover any interesting information during your research for “The Rebirth of American Cuisine and the Rise of the CIA?”

Metz: The research actually is how it evolved. It kind of made sense. It came from the regional cuisines of America which, in those days, was more predicated on the means of survival rather than innovative and creative cooking. It was about using the very best that was available. It was using what the land and each particular region had to offer. I think throughout the entire book and what tied everything together is that if you rely on regional ingredients and good sound techniques, you can produce great food.

TPN: How do you believe other cultures have contributed to American cuisine?

Metz: Right after World War I, you had an influx of immigrants coming to the United States, and of course what they brought with them — among other things — was their cuisine. You had some of the biggest restaurants run by immigrants.

I’ll give you an example. Mamma Leone’s of New York made unbelievable volume. [It was] not necessarily super great food, but food that they could offer at a reasonable price to many, many people. You had the Berghoff in Chicago and Zehnder’s in Michigan. And then you had Cecelia Chang taking Chinese cuisine — which in many cases was viewed as okay and cheap — she took it to a new level with the Mandarin House in San Francisco. Every one of the immigrant groups … left their mark, and in that way, they contributed to American cuisine.

TPN: Most college students have eaten fast food. What do you think about fast food culture?

Metz: I think it was a betrayal. It was a collusion of the media, the fast food enterprises and the beverage industry. It preyed on the young and innocent and needy. I have nothing against a hamburger with fries. But once you start supersizing it and people only have the means to eat that and have to eat that seven days a week — that’s the bad part.

TPN: What is your favorite meal to make?

Metz: It’s basically comfort food. Food that is slowly cooked. For instance, veal shanks, lamb shanks, oxtails — those are food items that you need to cook slowly as you develop the sauce. Living in California now, we have all kinds of things in our garden.

We have 220 olive trees — we are going to make our own olive oil. We have all the fruits like peaches and apples. We have guava. We have figs. We have hawthorns. We have all kinds of fruits and vegetables, and it makes a difference when you can have these fresh [ingredients] — even from your own place or from farmer’s markets. Quality is not necessarily the one that looks the best. It’s the one that tastes the best.

TPN: What has been the highlight of your career so far?

Metz: The highlight is really that very unique opportunity to be president of the Culinary Institute of America. We were able to take the school that was pedestrian to some degree to a level where we offered an associate’s degree and a bachelor’s degree in culinary arts. We basically introduced the idea that chefs should have and would benefit from an education.

One of the greatest moments — no matter where I travel, no matter where I go domestically or internationally, I always see graduates of the school. It is great to see how we, in a small way perhaps, have allowed them to achieve their goals and to see them successful. There is no greater pleasure that any teacher would have. It’s basically the legacy that you leave. Those people who have benefited from your education and moved on and become successful on their own.