Review: ‘Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom’ is solid, if inexact, adaptation of a classic

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” a play by Pittsburgh native August Wilson, was adapted into a film by director George C. Wolfe and writer Ruben Santiago-Hudson.

January 22, 2021

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” a play by Pittsburgh native August Wilson, was first performed in 1984 at the Yale Repertory Theater in New Haven, Connecticut. More than 36 years later, director George C. Wolfe and writer Ruben Santiago-Hudson adapted the play into a film starring Viola Davis and the late Chadwick Boseman.

The film had a limited theatrical run in November, then became available to stream on Netflix on Dec. 18. Overall it’s a very good adaptation, with strong performances that bring Wilson’s words to life.

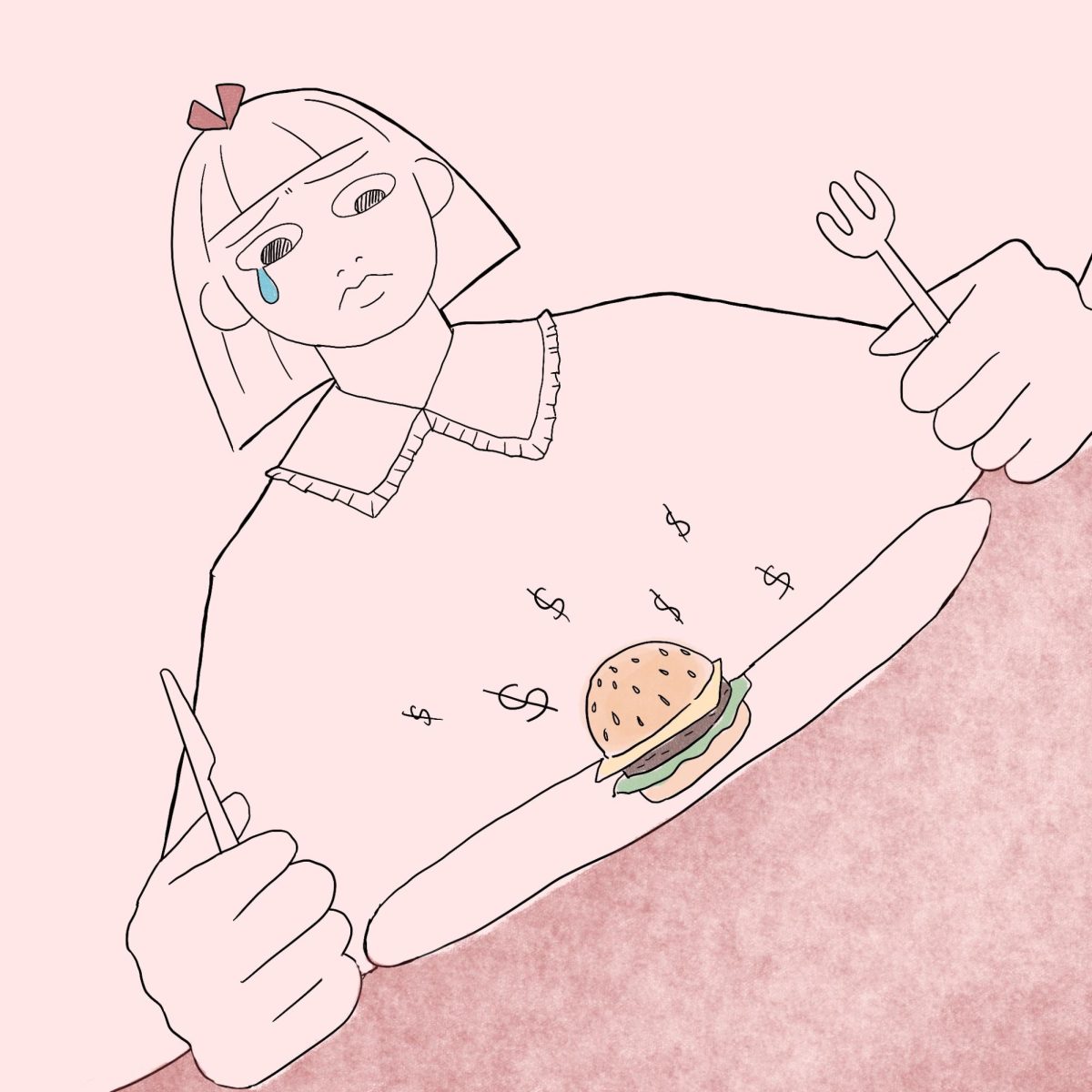

The events of the play and film take place in a recording studio in Chicago during the 1920s. Ma Rainey and her band are recording her new record, but several incidents make the process rather long and troublesome. The plot, a fictionalization of the real-life Ma Rainey’s blues recording career, is a meditation on how Black people fit into a white world where they are, as the character Toledo calls them, “leftover[s] from history.”

The filmmakers of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” took into account historical accuracy. A nice little detail in the film occurs in a transition early on that uses newspapers from The Chicago Defender, a Black-owned newspaper that was highly influential during Wilson’s time. Incidentally, Pitt’s recently acquired August Wilson archive contains advertisements for the original “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” that appeared in the Defender.

August Wilson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author for a reason. I read the play’s script in anticipation of its release, and, even without watching a performance, the play gripped my heart and would not let go. The play often brings up the fact that white audiences don’t actually care about the Black performers themselves, only what they can do, and although all the characters are aware of this, they react to it in different ways. This play is a tragedy about Black people trying to navigate an unfair world and the ways they can fail. I was heartbroken when I got to the end of the script, and excited to see the film.

While the play is named for Ma Rainey, the real main character is Levee, a young trumpet player with a passion for music. He often butts heads with the rest of the band due to his desire to play the music his way as opposed to Ma’s. Chadwick Boseman unfortunately passed away from cancer during the film’s postproduction, making Levee his final role.

Despite the tragic circumstances, Boseman’s performance is amazing as always. He portrays all of the emotions Levee goes through with his body language, and manages to make both sides of Levee — the cocky, playful trumpeter and the angry young man who has had so much stolen from him — come to life. The final scene, in which Levee talks to the white record company owner who’s trying to stiff him, is deliciously tense thanks to Boseman’s portrayal of Levee’s barely contained rage.

Davis in the role of Ma Rainey is also a delight. She has a quiet dignity about her, making it clear before her first line that she is the “Mother of the Blues” and she will be treated like it. Despite Ma being an abrasive character for most of her scenes, Davis also performs her quieter moments with the world-weary air of a woman who has put up with too much.

I was very happy to see that the film was explicit in Ma Rainey’s queerness, which was true to life. Rainey had relationships with women and even sang about it in her music, and the movie references this in the inclusion of Dussie Mae, a young woman Ma flirts with.

Unfortunately, Davis’s makeup always looks like it’s melting off of her, something that doesn’t seem accurate to any pictures of the original Ma Rainey that I’ve seen.

Of the supporting cast, Glynn Turman as Toledo the piano player is a standout. The stage directions from the play describe Toledo as someone who “understands and recognises that [the piano’s] limitations are an extension of himself,” and Turman’s performance brings that out. Like Davis, Turman gives off the impression that his character has seen a lot.

As is necessary for a film about musicians, the music is very good. Both Davis and Boseman take turns performing, and they sound great. The rest of the soundtrack is classic blues that I found myself nodding along to several times.

In terms of adaptation, the film expands on a few of the original scenes — such as Levee stealing Ma’s spotlight on the tour, or Ma leaving for the recording studio and getting in a car crash — and cuts out others. While most of these work fine, I do think the film is left wanting for the scene where Levee bets Toledo that he can spell the word “music.” Levee fails, but insists he’s right. Interestingly enough, in the original stage directions, Wilson writes that Levee “knows Toledo is right,” and I think that allows for an interesting set up for the rest of the play, where Toledo often lectures and scolds the much younger Levee.

I’m also not sure how I feel about the final scene changing from the original fade to black with “the sound of a trumpet … struggling for the highest of possibilities and blowing pain and warning.” The film chooses a much less subtle ending in which the record company owner records one of Levee’s songs with a white band.

Otherwise, the film is enjoyable on its own and a solid adaptation, and both Boseman and Davis’s performances are engrossing. The feeling that tensions within the band are about to boil over will keep you glued to your screen, despite the departures from the original script.

A previous version of this story stated that the filmmakers used materials from the August Wilson archive. The archive is not yet open to the public or researchers, and no items from the collection were used in the film. The article has been updated to reflect this change. The Pitt News regrets this error.