Panel discusses dismantling systemic oppression in education

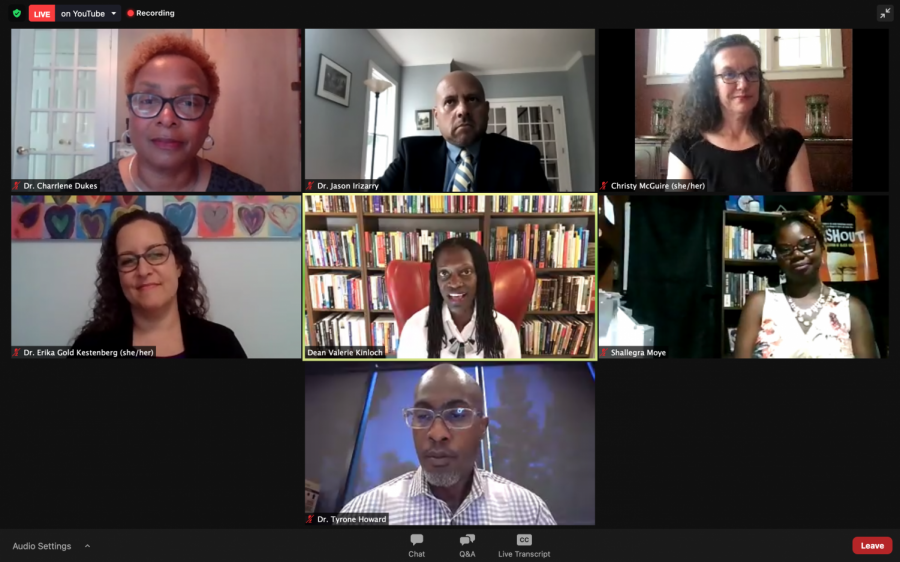

The Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion hosted its “Building a Just Educational System” event on Wednesday afternoon as part of Pitt’s annual Diversity Forum.

July 30, 2021

For Shallegra Moye, in order to dismantle systems of oppression in education, one must directly acknowledge them instead of avoiding the conversation. She said Wednesday afternoon that she was “grateful” to be a part of a Pitt discussion on “calling out oppression and injustice for what it is.”

“Calling a thing a thing, because so often that doesn’t happen. We skate around it and we dance around it, and as James Baldwin says, ‘We can’t fix anything we won’t face,’” Moye, Heinz Fellow project director at the Center for Urban Education, said. “We have to see oppression, we call it what it is in order to rally around for action, for community building, for collaborative participation.”

The Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion held the event “Building a Just Educational System,” which focused on how to remove oppression and injustices that prevent students from reaching their fullest potential. The event was a part of this year’s Diversity Forum, which focused on dismantling systems of oppression.

Valerie Kinloch, the dean of the School of Education, led the event and said it’s important to create policies that help communities “dismantle oppression” in educational settings such as K-12 schools and university campuses. She said diversity, equity and justice must be the “fundamental principles” of education, especially when it comes to mentors, peers and local community.

“I firmly believe this situatedness and this work has to be grounded in policies, practices and procedures that we need to rely on in order to dismantle inequities, injustices and oppression,” Kinloch said.

Erika Gold Kestenberg, CUE’s associate director of educator development and practice, said to dismantle this oppression, it must be done one policy, program or curriculum at a time. She said while in this process, we must examine ourselves and be self aware in order to truly make change to the system.

“Literally step by step, examining it, and examining ourselves in the process. Are we really committed to this, and what are our barriers internally?” Kestenberg said. “Where am I having trouble letting go of power or privilege in a position when we’re really fighting for and working toward equity and justice?”

Tyrone Howard, the associate dean for equity and inclusion at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, said it’s important to listen to young people in these discussions, as they “engage” with these systems of oppression every day.

“I would argue most importantly, we need to listen to young people. They’re the ones who engage with these systems every single solitary day, and they have a lot to say,” Howard said. “And the question is do we want to hear what they have to say, because their indictments are stinging but accurate. They’re harsh, but on point. They’re very difficult to comprehend, but yet so much a part of their day-to-day realities.”

When asked how to tear down structures of white supremacy and oppression by restructuring history taught in school, Howard said “banning” the teaching of race and racism in schools contributes to upholding it. So far, 22 states have proposed legislation to limit teaching about racism and white privilege, with some inaccurately labelling these ideas as critical race theory 一 a decades-old academic concept that race is a social construct and is embedded in policies and systems. Howard said this is a way to “concretize” white supremacy in the education system.

Howard added that it’s important to talk with officials in order to make sure they understand critical race theory and race in general.

“I think we all got to be more civically engaged,” Howard said. “We got to speak up and speak out to our elected officials to help them understand … what it means when you tell teachers you cannot teach about issues tied to race and racism, when we know the majority of students in our schools are going to be students of color.”

Howard said while classrooms are becoming more racially diverse, teachers in those classrooms are still predominantly white. He said this is a problem, as students of color may feel they can’t discuss racial issues that affect them.

“How do we think about this when we think about the reality being that we have an increasingly diverse student population while we have an increasingly non-diverse teaching population?” Howard said. “And those folks will be in front of our children, who are then going to feel like they are at will to not talk about cultural identities, their racial histories, all the things that make us who we are.”

Christy McGuire, a CUE doctoral student, said there is an “overrepresentation” of white teachers in schools, which contributes to the systemic oppression seen in the education system.

“Anyone who knows me knows I always talk about the vast overrepresentation of white teachers in our classrooms and the damage that does, but then also the teacher pipeline itself,” McGuire said. “The solution is not just to invite more folks of color to become teachers, because the pipeline itself is built from white supremacy tenets, and that’s all we’re going to produce.”

Kestenberg said ultimately it is important to have an open dialogue in order to communicate with those who disagree on the oppressive nature of the education system.

“There are connections there that we can make that we can then draw on and be in dialogue around,” Kestenberg said. “That it’s not me against you and there’s this issue, but together, we can unpack this issue, understand it better and move forward together in community. Building that just community that we’re seeking to do together.”