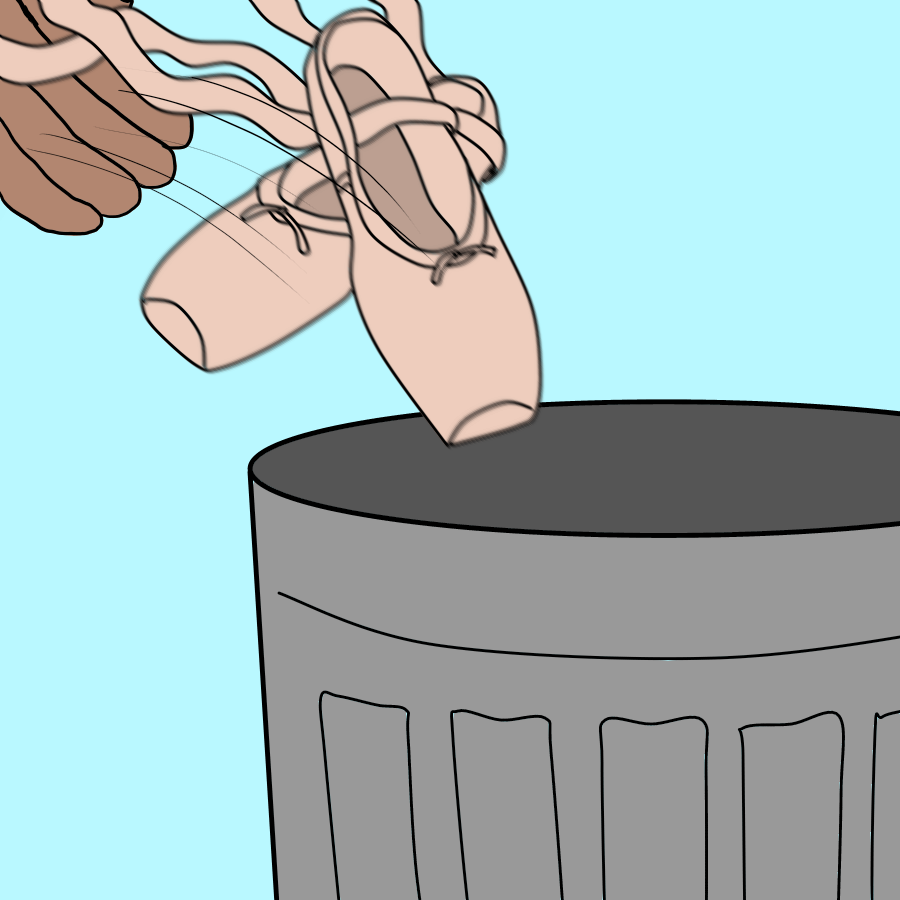

Opinion | Quitting dance was the best thing I’ve done

October 30, 2022

I remember wishing there was some fantastic story as to why my parents put me in dance. I wanted something to tell people when I became a professional. I wanted it to be that my mom noticed some kind of innate talent in me, instead, it was her second option after I was too scared to get on the beam in gymnastics.

I took my first mommy-and-me dance class when I was 3 years old and started competing when I was 8. For so many years, dance seeped into nearly every aspect of my life. Everyone at school knew I danced, because it was rare if I came into school not wearing my cheap team jacket with my name proudly embroidered on my chest. It was always a topic of conversation at family gatherings, and for many years, the only future I imagined involved a career in dance.

The insane capabilities of young dancers are a phenomenon that is recognized and capitalized on within the dance community. I didn’t take dance seriously until I was in middle school and realized that I could actually be good. Until then, I was consistently in the back line, just going through the motions.

I don’t know what led me to flip the switch, but there was no going back once I did. I spent an entire summer trying to fit the ballerina mold. Alone in my room every night before bed, I did every stretch imaginable, followed by a lengthy ab routine. I know now that behavior wasn’t healthy, but I couldn’t come to that conclusion at the time when I was praised for it.

It was a weird time in the dance community when teachers began to recognize the negative effects of enforcing a certain body type, and they attempted to remedy it. My ballet teachers told stories of how restrictive their teachers were and how they didn’t want us to feel the same pressure, but they still showed us the glamorous pictures from their professional performance, making it seem like their struggle paid off. Our teachers said we didn’t need a certain body type to dance, but whenever we took trips to the ballet, every woman on stage was so small.

In high school, I spent more time on schoolwork and fewer hours in the studio. I could see myself getting worse, and instead of being happy about what I could do, I could only focus on what I lacked. One of the hardest things about dance is that there is always room for improvement. You may give the best performance of your life and receive a score full of critiques.

I started to develop a mental block that stopped me from even trying, despite how much I wanted to. It showed the most when I had to do turns, because they require the perfect amount of force and balance to do the right amount of rotations while also landing. After many frustrating miscalculations, I stopped trusting myself, and every time I attempted more than a double, I ended up slamming my foot on the floor.

The combination of my negative progress and the loss of attention from people whose opinions I valued so dearly were the final nails in the coffin of my already dwindling love for dance. The same teachers who used to use me as the class examples didn’t even bother to correct me anymore.

It also hurt to see the younger girls who weren’t burnt out like me. The same teachers encouraged them to shoot for the stars and strive toward careers in ballet, while I was told to be appreciative of dance for its beauty and not necessarily partake. I felt that I failed. I didn’t work hard enough and now my opportunity had passed.

My fear of not having anything stopped me from quitting earlier. My friends at school picked up new sports every season and made friends with the people they played with. I felt stuck because I had never played any other sport. Once I quit during my transition to college, I had no idea what to do with myself. I went from having no free time, to being forced to figure out who I really was without the “dancer” label.

Once I started to embrace the freedom from my dancer identity, I learned that I’m a multifaceted person. Dance is known as a very restrictive activity with strict rules, but it wasn’t something that I noticed until I quit. I always thought it was ridiculous to keep my hair long only to tie it up and keep it contained while dancing. I started cutting my hair short during my first year of high school, but my instructors only allowed that hairstyle in the summer. Now I always keep it short and can even have bangs. My hair isn’t part of a uniform anymore, but a piece of my self-expression.

I also remember the summer before college when I realized I could get another piercing in my ears. It was something that had never even crossed my mind, because anything more than a single stud on your earlobe wasn’t allowed at my dance studio. It seems silly, but those extra sterling silver studs still remind me of the autonomy I gained back.

When I got to college, I found the thing that consumed most of my time turned into a fun party trick. Every once in a while I’ll remember that I can stand on my head or do a double pirouette.

Looking back, not everything about my experience was negative, and I’m grateful for the lessons dance gave me. I still love classical music — especially the songs I used to perform to fill my chest with intense and indescribable emotions. I love storytelling in all its forms, but especially in visual art.

With the distance I have gained I can still appreciate the beauty of ballet. I’m no longer sad that the chapter is over, but instead grateful that I got the opportunity to dance, and now I move on to what comes next.

Jameson Keebler writes primarily about pop culture and current events. Write to her at [email protected].