Opinion | Just feel bad for like ten minutes

April 13, 2023

In the last decade, a new sort of white feminism has developed, often likening girlhood to a Greek tragedy. Without the added contexts of class or race, this creates a very particular narrative of victimization that often obscures the reality of privilege.

In the last three years, the entrance of a white feminist framing into the world of interpersonal relationships is evident and transformative. It’s best understood in two ways — the pathologization of every experience and the assertion that rejecting discomfort is a revolutionary act of survival.

The pandemic led to an increase in demand for mental health services. Even people who did not feel the pandemic’s material impacts were still tormented by their inability to ignore those impacts on others. There was a small minority of people who were not experiencing any of the extreme consequences of the pandemic. And yet they were the ones inundating social media and the news with infographics and newsletters — anything to encourage those in similar positions to know that their struggle of being bored and isolated mattered, too.

Who can forget the “Imagine” video, where celebrities from the comfort of their mansions, performed a song that includes the line “Imagine no possessions.” Was it a clumsy act of solidarity? Were those in our societies with more privilege attempting, pathetically, to reckon with their privilege? At first, it did seem like that was the case. Then, the infographics came rolling in.

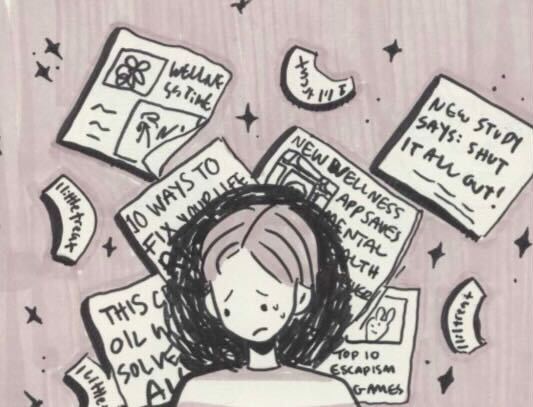

They were everywhere — encouragement to take a “break” from having to consider the conditions of others, templates for how to tell your friends that needing support was violating a recent boundary of yours or worse, the constant, unrepentant misuse of “emotional labor”.

At first glance, criticisms of this may come off as unnecessarily harsh. After all, the idea that we should never compare hardships has grown in popularity along with these practices of painting apathy as revolutionary, offering a knee-jerk defense to any pushback. TikToks about the pandemic, in particular, are full of assertions that we actually cannot compare hardships, from missed proms to entire countries lacking vaccines, because they are independent of each other. But are they? The people who died had entire lifetimes of experiences they missed, too. The fact that people in other countries didn’t have access to vaccines or healthcare is a direct byproduct of US and EU-backed hegemony. Why pretend otherwise?

I get that missing adolescent milestones is disappointing, but what I haven’t been able to understand is the idea that comparing struggles is somehow irrational — or even cruel. Even less, the idea that “focusing on yourself” by ignoring the actual, unbearable suffering of other people is an act of self-care. Why shouldn’t we, in the richest, most violent country in the world, compare struggles?

This problem, unsurprisingly, comes from neoliberal ideas of individualism. It doesn’t matter if you phrase complaints in psychological terms or loosely-grasped frameworks of class consciousness or feminist theory. By projecting them to this scale, you’re playing into a political strategy that encourages you to treat your life like a project under constant revision. You’ll never be satisfied and you’ll never realize the privilege required to pay that much attention to yourself. And most importantly, you’ll never try to help improve conditions for other people.

This type of commentary on selfishness or apathy normalized in recent years often runs the risk of being adopted by the right-wing’s “snowflake generation” rhetoric. But truthfully, you have to consider what infographics, articles prompting the reevaluation of relationships and messages of solidarity were created for. They were created to inform — perhaps imperfectly — about pressing issues, to warn people in precarious positions, and to tell the countless people forced into unlivable conditions that they held real power and had a future to look forward to.

The language used to describe these situations — in particular, the language used to describe abuse — is rendered effectively meaningless from overuse. All of a sudden, anyone who makes you feel bad is “toxic,” regardless of their criticism. Or they’re a narcissist. Or they’re needing more “emotional space” than is fair.

Aside from showing how irrational these abrupt boundaries seem to those witnessing them, the chronological growth of “therapy-speak” as a concept does more harm than good. In the tweeted replies to this Bustle article, there are people attempting to categorize the very behavior that inspired it as “narcissism”. It all looks a bit bleak.

An article that went semi-viral in December of 2022 detailed the end of a relationship in the lexicon adapted over the years to describe routine, unending misogyny that manifests in relationships and eventually becomes abuse.

However, the situation described is that of a messy, disappointing breakup, and not much else. Why use terms like “forcing my silence” and “refused shame” in an article about a relatively ordinary experience? Why co-opt the language developed to discuss abuse and the conversations surrounding healing to talk about breakups on such a large platform?

It all comes back to the idea of normalizing individualism by dressing it up in clinically approved or even attempted “revolutionary” language. This worsens the more we paint womanhood as a monolith — the more we encourage people to cut off their friends and family or speak to them like an HR department terminating an employee at the slightest hint of discomfort. In doing this we are just reaffirming the idea that we have no responsibility to each other as people — or to ourselves — to recognize when we are wrong or acting as byproducts of our environment.

We have to realize that the concepts of finding and choosing joy and peace in the bleak reality of suffering were created by and for people in actual marginalized positions. To use them as justification for asking some minimum wage employee to remake your coffee, or for your inability to accept legitimate criticism, is an act of delusional prejudice. To use the language of abuse and violence to describe your own unrelated conflicts paints a miserable picture for actual victims, who see their reality grow further and further warped for the sake of someone’s desire to dominate a narrative.

Feeling bad for a few minutes is not a hardship. You’re not a victim because someone embarrassed you by pointing out your blind spots. They’re not doing it to spite you, or “dull your shine.” They’re doing it because you’re a part of the world, and you might as well be aware of what happens during your time here.

Sofia Uriagereka-Herburger writes about politics and international and domestic social movements. Write to her at sou5@pitt.edu.