With the sheer number of minds pulsing through the TikTok algorithm at any given moment, you could spend your whole life trying to deconstruct “delulu girls” and “tomato girls” and “coastal grandmother girls” and the girls who get it and the girls who apparently don’t, and in the end you’d have accomplished very little.

Until we stop taking it at humorous face value, this toxic wheel of seemingly harmless content will keep legitimizing the worrying notion that there are inherent, significant differences between the sexes — and deprive us of appreciating human moments as human, not gendered.

Naming behaviors as “girl” things reinforces the idea that there are important differences between men and women, full stop. I don’t care if they’re humorous and lighthearted — I also don’t care if they’re accurate. The “differences” we notice are simply products of systems of patriarchy and gendered divisions of labor.

Take “girl dinner,” for instance. Maybe it’s true that women, more than men, like to arrange lots of smaller, seemingly unconnected items for meals, rather than putting together one or two single dishes. But we have to go deeper — why is that?

My two cents is that it’s either an internalized fear of eating full meals rooted in unrealistic body image and harmful messaging pushed on women from childhood, or that it’s a reflection of the disproportionate amount of emotional labor performed by adult women. This includes planning schedules for others, thinking out meals and directing household tasks, leaving little mental space or energy to cook full meals.

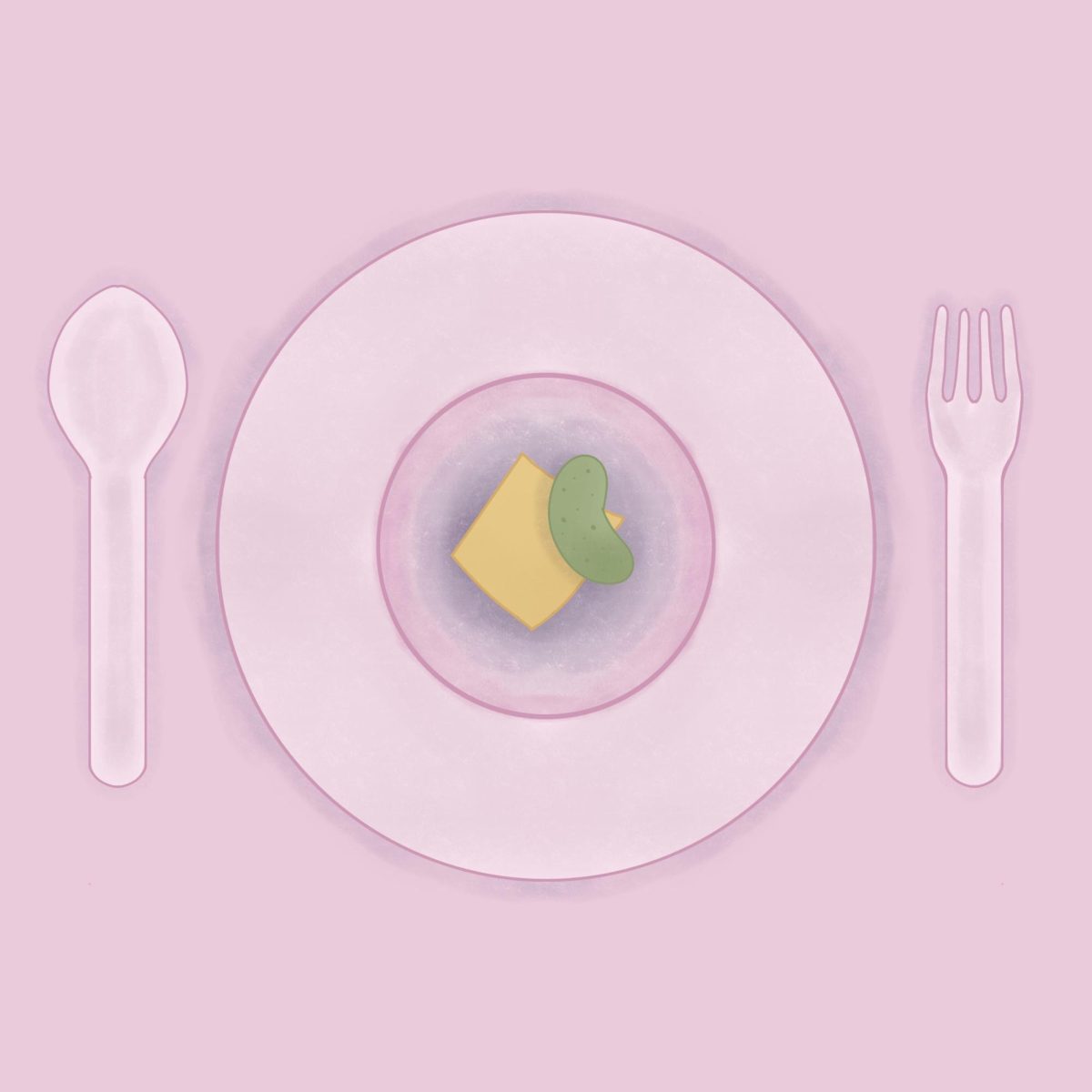

We don’t have to agree on why it is, and we can also acknowledge that it’s fun to have dinners composed of all different things — even though most of the “girl dinners” I saw were portrayed as funny precisely because they were so small, like a single piece of sliced cheese. The issue is that the trend of “girl dinner” validates this behavior at the surface level and treats it as something that women just do, have always done and will always do — the same sort of “inherence” reasoning that “justifies” calling men pigs.

The other major point of concern I see here is the underlying message that specific behaviors are not just inherent to genders, but are themselves gendered in the first place. Again, there’s no denying that there are differences in the degree to which certain behaviors are expressed among genders as a result of our system of patriarchy. But when we associate some behaviors with “girls” and others with men — because that’s how it always is, men are men and women are “girls” no matter their age in this infantilizing discourse — we reinforce the idea that things have a gender. We’re right back at more convoluted, adult versions of “pink is for girls and blue is for boys.”

Take “girl math,” the other trend that’s taken over my “For You” page and often makes me want to claw my eyes out. Again, it’s humorous at first glance — hardy har, if I make coffee at home instead of buying it out then I’ve made $7, girl math! — but more worrying upon second glance. In the case of girl math specifically, it’s hard not to spot the messaging right under the surface that shopping excessively, spending money irresponsibly and encouraging consumerism are feminine traits and “cute.”

Beyond even that, though, is calling this logic a “girl” thing at all. Is it really a gendered response to feel like you’ve been a little thrifty when you return something for your money back? No — and yet we’re talking about it as if it’s something exclusive to women.

In reality, what these trends identify are often just silly human behaviors that get arbitrarily sorted to one gender or another. Thinking about the Roman Empire is for men, because empires and war and history and intellectualism, naturally, are masculine, and dancing around with your friends is for girls and it’s cute because you put that clip from Greta Gerwig’s “Little Women” that goes “How I love being a woman!” in the background. No! These are fascinating glimpses into the richness of human life, into how our minds work, into what brings us joy!

Some of this messaging has genuinely good intentions. Captions like “This is girlhood,” “Girlhood is beautiful” or “Men will never understand x thing” all ultimately aim at fostering cohesion and solidarity among women in their own questionable ways. We can understand this as a response to gender-based oppression — an urge to build community, to legitimize each others’ experiences and interests and to build a safe space free from misogyny. Unfortunately, it often backfires into gender essentialism and ends up hurting everyone anyway.

In attempting to fight against derisive stereotypes, the third-wave feminist response usually goes, “No, femininity is actually beautiful.” Being emotional, being gentle, loving your friends or enjoying fine sensory experiences are all beautiful. I agree wholeheartedly that we should celebrate all of those traits in everyone — but the idea that they are inherently feminine goes right back to that same insidious Regency narrative that men are unfeeling cavemen and women are the delicate diplomats whose role it is to shape them finely and temper their tempers.

TikToks about female friendships often toe the line between very real appreciation of the power of friendships between women as resistance to patriarchy, and gender essentialism regarding the emotional capabilities of the genders. Of course it’s essential that women all have each others’ backs. Of course there are instincts that the vast majority of women will develop from childhood that most men will not because they don’t face gendered oppression.

But while I’m sympathetic to trends that aim to build female solidarity, I also think it’s beyond time to go further than this tired insistence that there’s something that women possess that men never will, that the only place for mutual support is among women and that men could never possibly understand the depth of friendship between women. Love is a human trait, not a feminine one. We gain nothing by insisting that only some people can understand it.

Nobody can reasonably expect TikTok to foster productive, nuanced discussions on the social construction of gender. Of course short-form media with endless scrolling and an algorithm that incentivizes trend participation and keyword use makes “girl math” and “only girls will understand” content thrive — it is quite literally what makes the app tick.

My concern is that consuming and participating in this media leads people to internalize these sorts of black-and-white gender divisions and actually reinforce gender stereotypes in their real lives. This comes at a time when we were just finally starting to culturally move beyond simplistic notions of gender differences. I bet at least one person you know owned a “Raise girls and boys the same way” T-shirt circa 2016. If we were far along enough then in deconstructing bioessentialist conceptions of the differences between men and women that it made it to the fast fashion cycle, why are we returning to this pointless narrative now?

Livia Daggett does love that version of “Little Women” and does know how to take a joke — they promise. Email them at LED88@pitt.edu.