“Poetry Unplugged” proved that words can create community out of consternation, oppose oppression, promote self-expression and guide enduring change over the weekend.

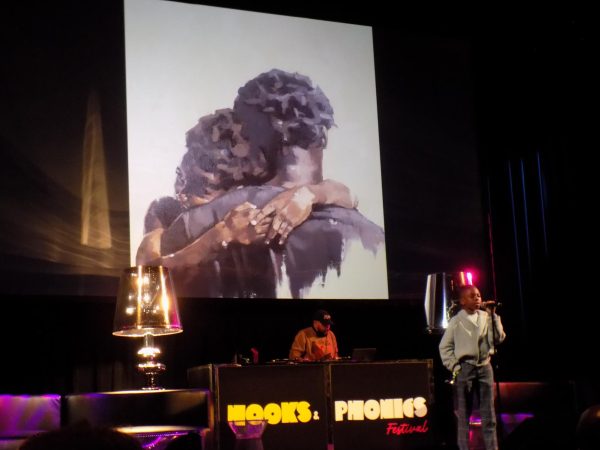

The August Wilson African American Cultural Center’s inaugural Hooks & Phonics Festival celebrated BIPOC stories and voices through poetry and hip-hop events. At 8 p.m. on Friday, Jan. 19, the three-day festival kicked off with “Poetry Unplugged.” Poets, each accompanied by corresponding visual art projected on a large screen behind them, performed readings of their work. Upbeat sounds by DJ Selecta filled the auditorium and had everyone nodding along with the beat, ensuring that as the clock neared 11 p.m., the audience didn’t go gently into the good night.

AWAACC, a non-profit art center, sold tickets for individual days for $45 and festival passes for all three days for $120. It was not a full house, but it felt like a home with the candle-lit lobby lined with tables featuring independent BIPOC artists, the poets’ merchandise and the conversational nature of the poets’ readings. Banter between host Orlando Watson and Selecta filled the stage, which mimicked a living room with its couches, plush maroon rug, shining silver lamps and ambient lighting.

On Saturday, Jan. 20, Rapsody headlined the second day, “State of Emerging Emcees,” which featured Chelsea Pastel, Jimmie Hustle, Ron Johnny, KeilyN and Nairobi. The festival concluded on Sunday with “Fan-tas-tic Forever: An Ode To J Dilla,” featuring jessica Care moore and Slum Village as well as the Urban Art Orchestra, De’Sean Jones, Khemist, NNS, Jeremiah Marcel and Yusef Shelton.

Watson, the event’s host, curator, poet and the senior director of programming at AWAACC, said he thinks the festival functions as a space for the BIPOC community in Pittsburgh to feel comfortable with their identity.

“I believe that the Hooks & Phonics Festival will serve as a safe space for Pittsburgh’s BIPOC community to fellowship and find the beauty of being true to the current version of themselves,” Watson said.

aja monet, a Grammy-nominated surrealist blues poet from Brooklyn, NY, said the festival’s focus on BIPOC voices makes the event truthful to America’s historical and current art scene, which was founded on Black artists.

“Being a Black artist … the cultural work that we have contributed to this country is the fabric of this country. Any time we can acknowledge the true history of America and what has made America what it is I think is truthful,” monet said. “I’m just a part of the fabric of a quilted existence here in this country. I’m one small stitch maybe in that.”

monet’s debut album “when the poems do what they do” is nominated this year for a Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Poetry Album. Despite the name of her nomination, monet does not consider herself a spoken word poet. Instead, she said she’s just a poet, since poetry was historically verbalized until innovation took it from mouth to page, categorizing it as a written art form.

“I always make it a point to make sure that I clarify what I do is poetry, I don’t consider it spoken word,” monet said. “You know, poetry has been and will always historically for me be an oral tradition. The literary invention of the printing press, all of that, came after the oral aspect of poetry, so I always try to make it clear to people poets have always spoke[n] their poems, it’s just the western European world made poetry seem like it’s only written. So I’m just a poet.”

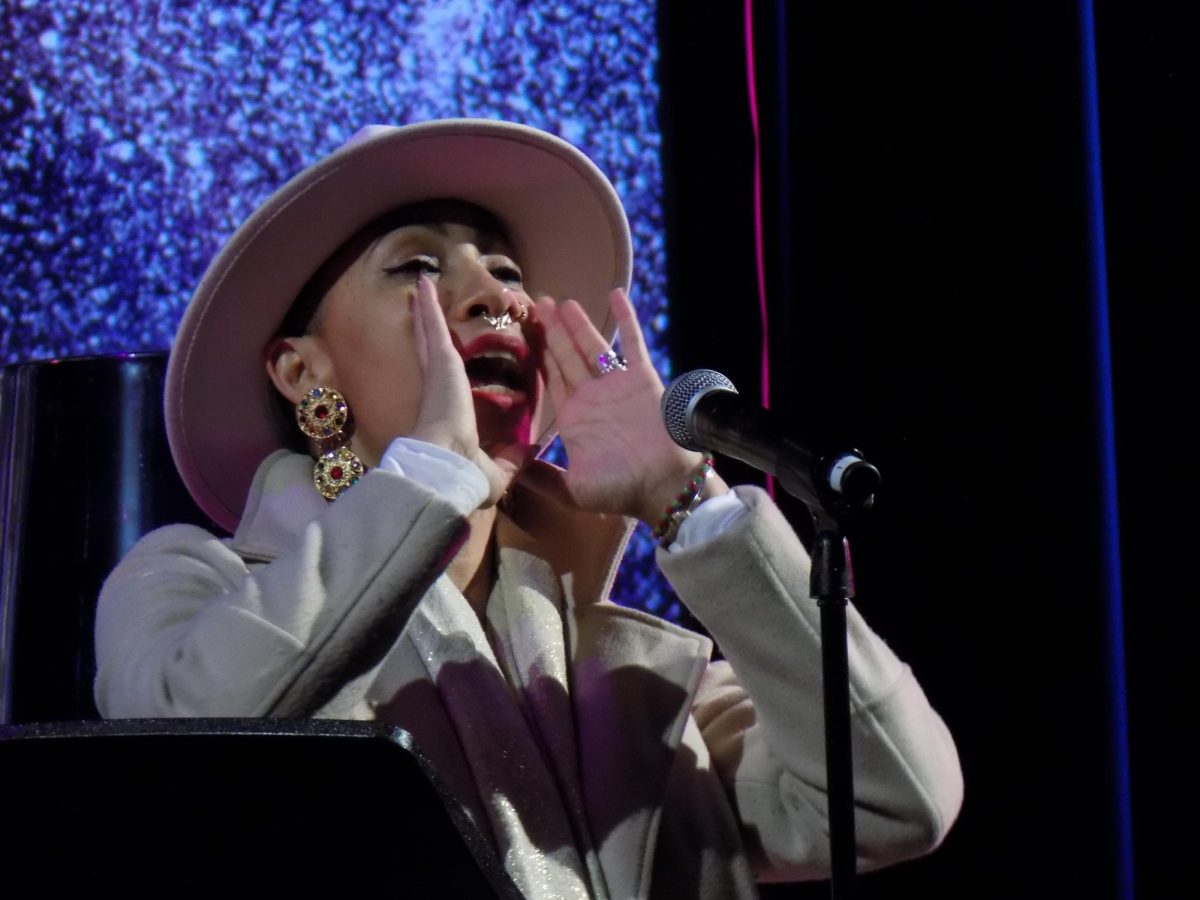

monet was one of seven BIPOC poets that graced the stage on Friday. The others included New York’s 10-year-old honorary poet laureate Kayden Hern, poet and art journalist Jessica Lanay, 2022 ICON award-winner LoveTies, Orlando Watson, poet, performer and TEDWomen speaker Sunni Patterson and poetry slam champion Ed Mabrey.

“Poetry Unplugged” centered around Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy and addressed themes of community, violence, justice and unification. Ed Mabrey and Sunni Patterson’s performances included moments of song, and Patterson closed out the night by doing crowd work, having audience members pick from her deck of affirmation cards and then incorporating them into her final poem.

Patti Emory, who has followed Sunni Patterson for many years and attended “Poetry Unplugged” to see her, was emotional after seeing her perform. Through tears, Emory said the night was like a religious experience.

“I think I’ve only ever cried like this at church,” Emory said, wiping her tear-stained cheeks.

Watson said the vulnerability of spoken word poetry rings true with those who listen to it, and that its ability to elicit beneficial introspection is inspiring.

“The art of spoken word exudes a vulnerability that resonates with listeners,” Watson said. “[It] inspir[es] them to self-examine, unpack issues, seek solutions and find their voices.”

monet said poetry cues people to be aware of their own feelings and those of others, which is relevant now.

“For me, poetry is how we get people to tap into their innermost truthful feeling selves — sentient selves — and we need that right now. We need people who are able to listen to the feelers and the healers of the world, especially when we see what is happening in Gaza and the Congo,” monet said. “This is a time that if we are not awakened to the hearts, minds, and lived experiences of the most vulnerable, then we will succumb to the worst parts of ourselves as a people.”

“Poetry Unplugged” served as a reflection on the historical and present conditions of the BIPOC community in America and a call to action for the future. monet said right now poetry must not dance around the truth and courses of action, but be perspicuously demanding.

“I think if poetry has any function right now, it needs to demand. We can’t play games with hearts and minds,” monet said. “At this point we have to be very clear and concise about the truth and what we can do about it. We have to do something with the truth that we feel.”