Pittsburgh is home to some of the most important figures in sports history –– so many the Steel City should have its own Mount Rushmore. Why isn’t there one? Mount Washington has plenty of room where a large Iron City Beer billboard currently sits. But a monument of this kind can only have four faces.

Cutting the nominees down to four might take longer than actually sculpting the thing. But the city and the powers that be can only deliberate over three. Sam Clancy’s spot is guaranteed.

In Pittsburgh, June 24 is Sam Clancy Day. The corner of Bedford Avenue and Roberts Street in the Hill District is named Sam Clancy Way. The next step in Clancy’s immortalization — before he’s sculpted into Mount Washington, of course — is Pitt men’s basketball retiring Clancy’s No. 15 jersey into the rafters of the Petersen Events Center on Jan. 18.

Clancy’s No. 15 is just Pitt’s fifth men’s basketball jersey retired, with the last occurring 15 years ago for Brandin Knight’s No. 20 in 2009.

Clancy averaged 14.4 points and 11.6 rebounds per game as a four-year starter for Pitt basketball. Clancy is the only Panther to ever eclipse 1,000 points, 1,671 total, and 1,000 rebounds with 1,362 total — the most in school history. Despite a successful college basketball career, Clancy was a professional football player in both the NFL and USFL.

Pitt men’s basketball head coach Jeff Capel made the announcement during Pitt versus Cal in front of almost 50,000 people at Acrisure Stadium. It was a complete surprise to Clancy, who stood next to sophomore guard Jaland Lowe, who will wear Clancy’s No. 15 for, “as long as he’s here,” according to Clancy.

Clancy wasn’t sure why he was on the field at all. The original plan was to honor Pitt football’s 2004 and 1979 — who Clancy went to school with — Fiesta Bowl teams and call each player’s name individually. The plan then changed to showcasing the Pitt basketball team ahead of the season. The announcement, let alone the honor, was a complete surprise to Clancy.

“I’m told to stay on the field for the recognition,” Clancy said. “Because I played professional football, but not in college, the ‘79 team wanted me to come out on the field with them, but I said no, because at Pitt, I was a basketball player.”

The surprise was almost ruined several times. Multiple people said, “congratulations” to Clancy’s wife in the lead up to the announcement, but had to wiggle out of an explanation each time not to ruin the moment.

“I’m in everybody’s apartment, work space, all week after we got back from a cruise,” Clancy said. “Everybody acting weird towards me all week, cutting our conversations short. Everybody had meetings all of a sudden. On the day of the game, everybody was being weird towards my wife too, but it’s all because they knew I’d get the surprise out of them if we talked for too long.”

“The basketball team walks out. I’m standing on the sideline just to watch them get their honor,” Clancy said. “Then I’m told to walk out with the team, and I’m resisting. ‘Let these boys get their flowers, man, I’m an alumni and I support ‘em’. Then Matt Plizga [associate athletic director, strategic communications] puts his arm around me and says, ‘Walk with me.’”

Then, Capel said the magic words.

“Pitt men’s basketball athletics is going to honor a true legend in the city of Pittsburgh and Pitt men’s basketball when we retire Sam Clancy’s No. 15 jersey,” Capel said on the field.

“That’s when I just lost it. The emotion was real,” Clancy said. “I didn’t know anything. I look at the video now and I still get choked up because I appreciate the selection committee, Coach Capel and the basketball guys for recognizing me as one of them.”

The honor reinforced that Clancy made the correct decision 47 years ago to stay home and play collegiate basketball less than two miles away from his house at the University of Pittsburgh.

“I think Pittsburgh people are loyal. Pittsburgh gives you a small town, everybody appreciates you-type of feeling, even though we’re a big city,” Clancy said. “I came to Pitt because my family trusted Tim Grgurich [former head coach of Pitt men’s basketball] and the staff.”

Grgurich, a Lawrenceville native, knew what he had to do to keep Clancy, who was recruited by “over 200 schools,” local.

“Grgurich, unofficially, came to my house 50-60 times because of the outdoor high school summer league,” Clancy said. “Every day, he’d drive past the house on Bedford Avenue [the street now named after Clancy], and Grgurich ate dinner at my house. He knew every one of my relatives’ names. Pitt would come out, hang on the corner and just talk to you.”

Although Clancy was strongly leaning toward committing to Pitt, he kept his college options open into his senior season — until another local legend in the middle of a historic year vouched for Pitt.

“Who sealed the deal for me was Tony Dorsett [a Rochester, Pennsylvania, native who went on to win the Heisman Trophy that season],” Clancy said. “I was on the sideline for a rivalry game, Tony ran off during warmups and said, ‘Hey Sam, I’m telling you, stay home for your family, stay home for your community, and they’ll love you forever and take care of you, man.’”

First, Clancy had to take care of Pitt. With Clancy on the roster, the Panthers had four straight winning seasons and a 1981 Eastern 8 Championship. On the way, of course, Clancy grabbed a lot of boards.

“I always tell the basketball team that my rebound record is going to stand forever because everybody is shooting threes now. It’s a lot of long rebounds,” Clancy said. “I’m only 6’6”, but I came at a time when I had to play center.”

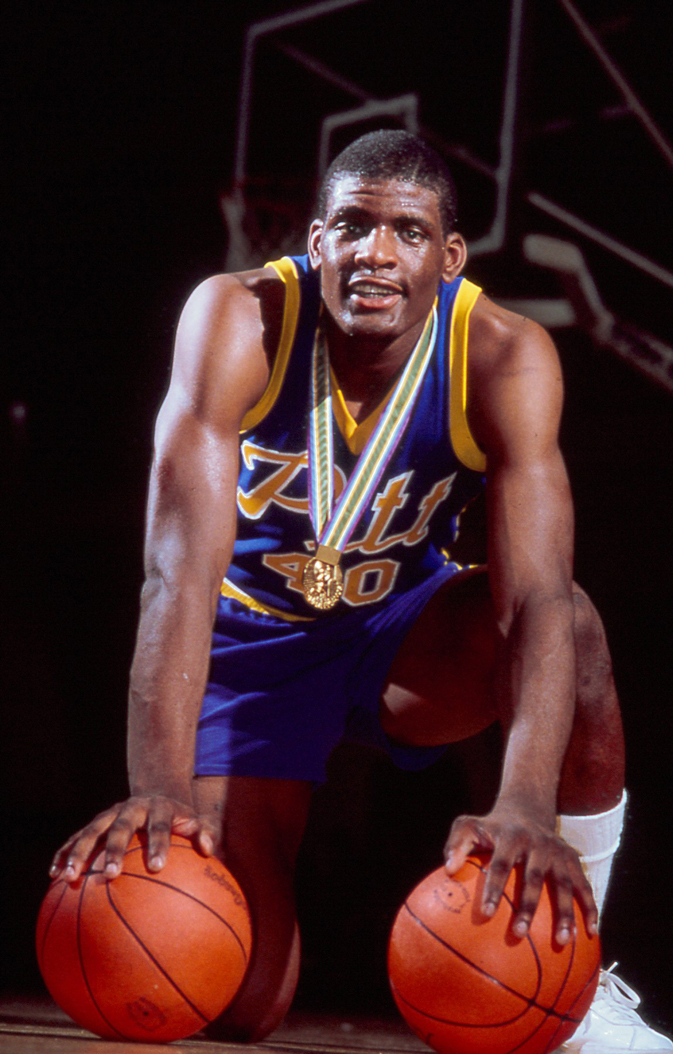

As a 1979 All-American Honorable Mention, Clancy tried out for Team USA in 1979 to compete in the Pan American Games, unsure if he’d make the team that was coached by legendary coach Bob Knight.

“We had two more days left of practice. One of the coaches on the selection committee, who was good friends with Grgurich, told me that coach Knight loved me because I’m his type of player,” Clancy said. “Physical, go after the ball, take no crap from anybody and push guys around. The coach said, ‘Just don’t mess it up in the next two days, and you’ll make the team.’ That just made me play more intensely.”

“I love playing against the best,” Clancy said. “It brings the best out of you.”

Clancy, who pulled down the fourth-most boards for the team, made Team USA alongside players that would go on to become NBA legends — Isiah Thomas, Ralph Sampson and Kevin McHale. Team USA went on to win the gold medal against Puerto Rico, and Clancy and his teammates were the first Team USA team to average more than 100 points a game.

Traditional fraternities only allow single membership, but Clancy was invited to every brotherhood he was around. The ‘79 Fiesta Bowl team wanted Clancy on the field despite never playing college football. Team USA added Clancy to the roster after competing with to-be NBA legends. This season’s basketball team wanted Clancy on the field and recognized as one of their own.

There’s one more fraternity Clancy’s name is wrongly missing from. It’s generally accepted that the NBA and NFL have fought over the draft rights of only three different athletes — Bud Grant, Dave Winfield and Dave Logan. Clancy is the glaring omission.

The Phoenix Suns of the NBA drafted Clancy with the 62nd overall pick in the 1981 NBA draft, and a year later the Seattle Seahawks of the NFL drafted Clancy with the 284th overall pick in the NFL Draft. Clancy should absolutely qualify, but historians have made an error.

“I have no idea why I’m not on that list,” Clancy said. “I should reach out to the NFL. Maybe this article will help correct it.”

Clancy thinks it’s because he never played in an NBA game at all but did have a productive professional career with the Billings Volcanoes of the CBA, where he averaged 11.5 points and 8.3 rebounds over 41 games in 1981.

“I got cut from the Phoenix Suns. Larry Nance and Craig Dykema, who was drafted the round after me, made the team,” Clancy said. “I was strictly a power forward, but Dykema was a swing player who could play the two or three position. When I got released by the Suns and was sent to Billings, Montana, the head coach said, ‘Sam, we’re looking for a bigger power forward, and already have a guy just like you [Truck Robinson]’. I was an inside player at 6’6”. You move me past 12 feet and I’m shooting air balls. When they say I played professional basketball, it was with the Billings Volcanoes.”

The obvious question is how Clancy, a four-year basketball star at Pitt, NBA draft pick and professional player in the CBA, got drafted by the Seattle Seahawks despite not playing football since high school.

“The very first day I’m in Billings, I get to the hotel and the light on my hotel phone is flashing, meaning I had a message,” Clancy said. “I go down to the front desk and get my pink slip to read the message. It was Chuck Allen [director of Pro Scouting] from the Seattle Seahawks who called and left his number. Why would the Seahawks be calling me? They’d only been around like five years, and I don’t play football. I call him back and he says, ‘Sam, I know you didn’t play football, but Jackie Sherrill [Pitt football head coach from 1977-81] gave us your name and said he thinks you can compete in the NFL.’”

Former Pitt football head coach Jackie Sherrill chased Clancy for all four years at Pitt. Eventually, when Pitt forced Grgurich to resign after the 1980 season, Clancy was fed up with the basketball program. He gave in to Sherrill’s repeated requests to come out for the football team, but after a week playing defensive end, Clancy returned to the basketball team for his senior season.

“With no football talent, no football skills outside of what I learned in high school, Sherrill put me as the backup defensive end,” Clancy said. “We had a serious offensive line that I was going against, and I guess I was doing OK against the starters. He said, ‘Play football for two years and I’ll make you an All-American.’ The new basketball coach, Roy Chipman said, ‘Sam, they say you’re trying out for football. But, if you want to play football, I have to build my team without you. You’re a star player, and we need you on the basketball team.’ Right then, I came back to basketball because that’s what I was — a basketball player.”

Clancy never told Sherrill he was quitting after a week with the football team, but Sherrill didn’t hold any grudges. Two years later, a single week of spring ball turned out as a de facto tryout for the NFL, and Clancy proved he could play both sports.

Allen originally said the Seahawks would sign Clancy as an undrafted free agent. But after learning the Washington Redskins had reached out to Clancy through the mail, Allen drafted Clancy in the 11th round as a complete unknown.

“After drafting me, Allen said, ‘What position do you want to play?’ I said I like scoring touchdowns because in my senior year of high school, I played tight end, so Allen drafted me as a tight end,” Clancy said. “Offense was hard, I’m not going to lie. It took me a while, but I impressed them because I ran a four-six and had decent hands. Next year with a new coach that was planning on cutting me, I got moved to d-end, which worked out because I liked hitting people, the physicality and my agility from playing basketball.”

Clancy spent two seasons in Seattle then returned home to Pittsburgh to play for the Maulers of the USFL — a rival football league to the NFL that produced several Pro Football Hall of Famers.

“The USFL was offering good money,” Clancy said. “You had a quarter of the league that came from the NFL to the USFL, so it was a competitive league. Steve Young, Jim Kelly, [and] I played with Reggie White. They all came from the USFL. I didn’t have one regular season snap in Seattle. My first sack came against Steve DeBerg in Denver in the postseason, and we won that game. That led the Maulers to come calling. The money was three times what I was making in Seattle, and I was coming home to my family, so it was a no-brainer.”

Clancy recorded 17 sacks, good for second in the league, in his first season with the Maulers. He then spent a year in Memphis in the final year of the USFL.

“The Seahawks still had my rights even though I was playing in the USFL and traded my rights to the Browns,” Clancy said. “I enjoyed those four years with the Browns. We were good, a playoff team. Everybody on the Browns were like brothers.”

Unfortunately, Clancy’s five-year stint with the Indianapolis Colts after his four-year contract with the Browns was the complete opposite.

“We had all the talent in the world. Eric Dickerson, two Pro-Bowl offensive linemen, All-Pro center, All-Pro tackle and All-Pro linebacker, and then in my second year there, we had the very first pick of the draft,” Clancy said. “In my first year with the Colts, I wanted to go back to the Browns, and they wanted me back too, but I had signed a contract.”

The Colts went 1-15 in Clancy’s third year and had both the first and second overall draft picks in the 1992 draft.

Clancy finished his NFL career with 30 recorded sacks — not bad for a multi-sport athlete who never played defensive end until he was paid to do so. His favorite two are against a pair of all-time quarterbacks.

“John Elway. There’s a picture of it on the internet. It doesn’t look like I sacked him, but I tripped him up,” Clancy said. “But my very first sack is really special with Steve DeBerg because, even though I was already on the team, it jump started my career. It got me home to the Maulers, and then to Memphis, and developed enough to end like this.”

After an illustrious professional career across four different leagues and in two different sports, Clancy is now the director of Pitt’s Varsity Letter Club and is responsible for athletic alumni relations — a pivotal role in the success of Pitt basketball.

If that big year is this year, it’s because of the sophomore guard wearing Clancy’s No. 15, Jaland Lowe.

“I told him, ‘This is your team,’” Clancy said of Lowe. “I think Lowe is a heck of a leader, a heck of a point guard, and can really score. I think we go as far as Jaland [Lowe] leads us.”

“I was here watching a little scrimmage, in practice, and I’ve seen that leadership, coaching other guys up,” Clancy said.” And don’t forget this is only his second year. So I’m honored. I’m honored that my jersey is getting retired, and I’m honored Jaland Lowe will still wear the number.”

Clancy’s legacy is undeniable — he out-maneuvered his way through any obstacle, around any naysayers and avoided any traditional boundaries that limit athletes to a single sport in a world of ever-increasing specialization.

“I hoped this day would come,” Clancy said. “I didn’t know if I accomplished enough to get it done. In my eyes, I think I could’ve accomplished more.”

Clancy lived a truly one-of-a-kind athletic life and is certainly selling himself short. His jersey will rest forever in the rafters of the Petersen Event Center.