Pitt lacks resources to develop Ebola vaccine

October 1, 2014

As Ebola continues to spread through African countries, and now, with one case confirmed in the United States, many people have expressed worry that the virus will find its way to their cities and towns.

But, according to experts, it’s unlikely the disease will have similar effects in the United States. While Pitt has historically contributed developments to vaccines, the University does not have the proper biosafety level clearance to work on Ebola, which is a level-4 disease.

One of Pitt’s most famous accolades is the development of the polio vaccine by Dr. Jonas Salk and his team. The vaccine began widespread use in 1955 and eradicated the disease in the United States. More recently, researchers at Pitt have been working to develop a vaccine for the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome.

Dr. Amy Hartman, research manager of the Regional Biocontainment Laboratory and assistant professor in the Department of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, has done extensive work with the Ebola virus during her career.

Hartman conducted her post-doctoral research with the CDC in Atlanta from 2003 to 2007. During her time there, she worked on curing the Ebola virus. In 2005, she worked in Africa in a post-diagnostic lab that tested patient samples for Ebola.

“I think it [Ebola] is very serious in Africa in general,” Hartman said. “But there is no huge risk to the U.S. or other developed countries.”

According to Hartman, the United States and other first-world countries have such strong health systems that, if someone brought Ebola into the country, it would not cause an epidemic like the one in Africa.

“If someone came here who was infected, it would be stopped pretty quickly,” Hartman said.

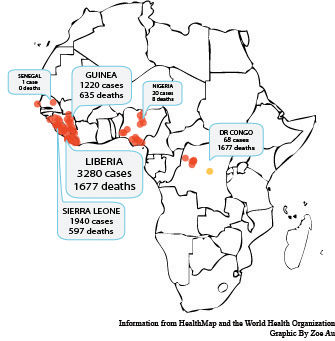

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa is the largest in history and also the first epidemic of the disease.

As of Oct. 1, there were 6,574 reported cases of Ebola in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone and one confirmed case in the United States. The disease has killed 3,091 people so far in the West African countries.

The CDC confirmed on Sept. 30 that an unidentified person in Dallas has Ebola. Their website says health officials in Dallas are “taking precautions to identify people who have had close personal contact with the ill person.” So far, the CDC hasn’t yet identified any other cases in the U.S.

Pitt is not currently able to work on a vaccine for Ebola, Hartman said, but is working on other important vaccines and therapeutics for other ailments.

“[Pitt] doesn’t have the biosafety level 4 to work with the live virus, but we do have level 3 for other viruses equally as important as Ebola,” Hartman said.

Some of these other viruses are yellow fever, H5N1 avian influenza and Rift Valley fever virus.

According to Hartman, the only way Pitt would be able to work on a vaccine for Ebola is in a “collaborative sense” with other universities and places that do have level-4 biosafety clearance.

They are not currently doing that, but Hartman said that there has already been work done by other places prior to this epidemic.

Janet Truebig, a first-year student in the Graduate School of Public Health in the Department of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, said she doesn’t think that Pitt should start work on an Ebola vaccine.

“Pitt has been really involved in the past, but I think we should leave Ebola to the higher-ups like the CDC and WHO [World Health Organization],” Truebig said, referring to the highly lethal nature of the disease and Pitt’s facilities, which aren’t properly equipped.

But, Truebig said she does think that there are ways to help Ebola patients in Africa.

“The big problem is people in Africa are scared of hospitals and medical workers,” Truebig said. “To educate on safety and good intentions is the biggest way to help. There is a low doctor-to-public ratio. They need help getting medical people down there to help with treatment units.”

As a student working with infectious diseases, Truebig said that she wouldn’t choose to work on or around an Ebola vaccine.

“You can stick a monkey, and it flinches and waves its arm, and the needle goes flying and it sticks you in the thigh, and it’s as easy as that to contract Ebola,” Truebig said.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior associate at the UPMC Center for Health Security, agrees that there are risks involved with making all vaccines but says that, if you follow the proper biosafety precautions, exposure should be prevented.

“The risk is very small, but never going to be zero,” Adalja said.

Adalja said he does not believe Pitt needs to start working or collaborating on a vaccine for Ebola, since the Ebola vaccine process is already on human trials in other places.

He would not, however, rule out Pitt helping other schools work on “wider human trial testing.”

“Pitt is no stranger to vaccine trials, since the polio vaccine was done here,” Adalja said.

In a Sept. 30 death-toll prediction released by the CDC, the death toll from Ebola was estimated to reach from 550,000 to 1.4 million people before this epidemic ends.

As terrifying as these numbers are, Adalja said they are not to be taken literally as a prediction.

“If you read the CDC paper closely, they back away from that number. It’s based on a model assuming nothing is being done,” Adalja said.

According to Adalja, Ebola is only spread through blood and bodily fluids, and, if the burial practices in these areas change, it would help stop the disease from spreading. Ebola can spread through contact with corpses as well.

But, Adalja said, people often underestimate how difficult changing practices in Africa could be.

“Sociocultural factors impede the ability of this message to get through to this population [there],” Adalja said. “There is a severe distrust of public health authorities [in Africa].”